Last week I was lucky to attend CraftCon 2025. Hosted by the Three Counties Cider and Perry Association, and held in Hereford. It was a really amazing two days, crammed with fantastic talks and, more importantly, just wonderful networking.

I was also honoured (and more than a bit terrified) to be invited to give the opening keynote, just as my friend and co-editor, Adam, was invited last year. And just like Adam, I thought it might be nice to publish my talk here on CR.

So here you go, a description of my journey of discovery of lost and extant central European cider and perry cultures (which is both wider and far older than you might have thought), a look at why most of them vanished and have been largely forgotten, and some small measures we and others are taking to restore parts of the lost cultural heritage of the traditional meadow orchards.

Good morning everyone. It’s an absolute honour to be invited to speak with such an incredible group of cider people. Though when I think about it, what Albert actually said was “your years of evasion are past” so it was more an ultimatum than an invitation!

So, despite usually avoiding public speaking like the plague, I felt I couldn’t, indeed shouldn’t refuse… But he also said it’d mean I’d be in the cool club, so that was the real clincher.

For those who don’t know me, my accent probably gives away where I am originally from, but I moved to Germany in 2008, with the last 15 of those years in a place called Schefflenz, well, Mittelschefflenz to be exact, a small village at the northern end of Baden-Württemberg, the big State covering the bottom left of Germany. And it was here that my fascination with cider, and perry in particular, was awoken.

Having been a long term home brewer and an active beer blogger at the time we moved there, I was most definitely a beer and fermentation geek.

But cider just wasn’t on my radar. Probably because coming of drinking age in the Ireland of the late 80s and early 90’s, it was basically just the odd pint of Magners or maybe an occasional al fresco flagon of Strongbow.

But for some bizarre reason, in 2012 I dipped my toes into making cider, and it quickly became what I generally refer to as a hobby out of control, as by 2019 we’d started selling the stuff.

I could probably fill this talk with the stories of how we started and the victories in proving to the Department of Finance that cider is indeed an agricultural product, so we were able to register as a farm. But for the most part, I think our cidermaking journey is not all that different to many of yours, it’s perhaps just the backdrop to everything we do that is different.

* * *

We use apples from our own orchard which was planted in 1958 so it pretty mature. That also started small, with a quarter acre with 30 trees bought from our postman’s mother for just over 1000 Euro.

Twice more, people offered us bits of orchard, as they couldn’t look after them any more, so we now have one-and-a-half acres of contiguous, mature orchard. Nothing is sprayed, and the whole harvesting and orchard “management”, for want of a better word, is a very manual affair.

The varieties we use are those that were popular in 1950s Germany, but they’re pretty representative of what are customarily the types of apples used in pretty much all of central Europe for making cider, and that is, varieties that tend to be acid-led with little to no tannin. Most could be described as dual function dessert and juicing fruit, and some, which we’d call typical Mostapfel, are considered just good for pressing.

Not long after I started and began reading more about cider, I thought I had to plant tannin-rich apples to make a decent drink, but over time I realised that there was a huge and ancient European tradition that used the types of apples we have. So in the end I realised it would be doing a disservice to our local cultural history to try and simply copy a style from another country.

Though by then I had already planted a bunch of English and French varieties with appreciable tannins, and have since grafted more, but I still haven’t had the use of them.

I began pressing using a range of basket presses and old mills that I had restored – another ridiculous hobby – but since we started selling, I switched to a hydropress, just to speed things up. Though I miss the workout the manual presses gave me!

Fermentation is in a mix of plastic, stainless steel and wood, with batch sizes ranging from 60 to 300 litres. And I’m quite happy to have very small batches, as it means I can experiment without too much risk. And I do like to experiment! Whether it’s trying out different wine and beer yeasts or co-ferments with different fruit, like quince, sloes, cherry plum or medlar.

Those of you who may have read some of my earlier Cider Review articles will know I also like to try to recreate historical recipes, whether that’s adding clary sage to ciders or making boiled perry, or more modern experiments, like trying to make an annual perry-beer hybrids, like a smoked malt Rauchbier perry or Belgian Witbier perry. Mostly so I don’t forget how to brew!

Small batches also mean we produce a wider range, sometimes up to 22 or 24 different ciders and perries a year, which keeps it fun and interesting.

Maybe one major difference that will sicken makers here in Britain, is that Cider, like wine in Germany, has a duty rate of 0%, and that’s regardless of the size of your operation. There is of course a sparkling wine duty, similar to rules here and elsewhere. But this certainly made it much easier to start selling.

But other than all those practical things, there was something else in the background, a canvas against which I was working that completely changed my perception of what we were doing.

Though I had of course noticed the amount of fruit trees that were scattered across the countryside near us, my focus was initially on our orchard, our own apple trees and minding my own business.

That changed when Anu arrived from Ireland on the 8th of December 2018, and she immediately became a catalyst along this journey. Ok, so a dogalyst not a catalyst.

* * *

The countryside of southern Germany is quite open. There are very few field boundaries or hedgerows, and the whole place is criss-crossed with these Feldwege, or field tracks. And people are generally free to walk where they like, as a farmer’s fields and meadows are usually scattered across a wide area, not in some enclosed landholding.

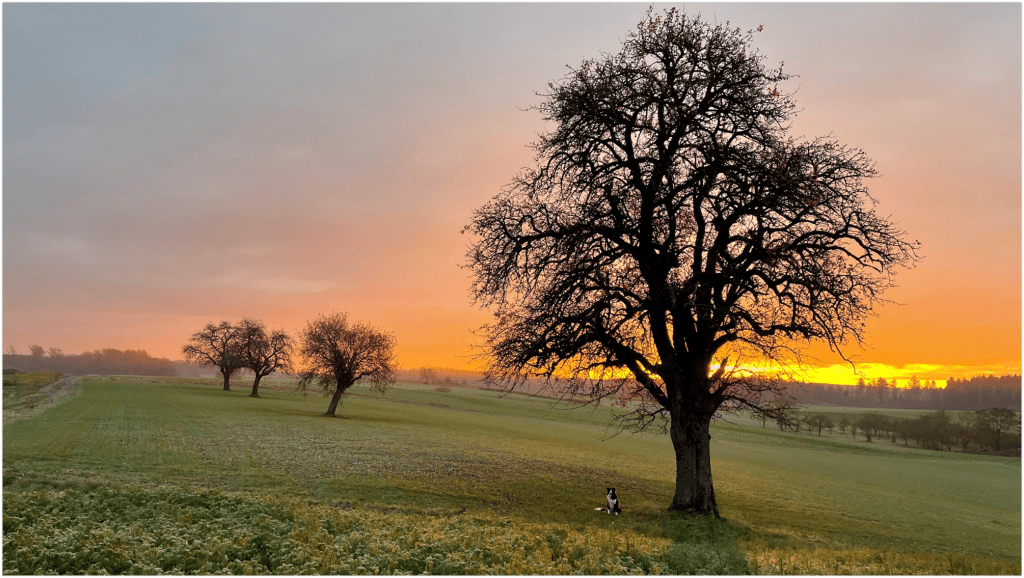

But scattered across this patchwork of fields are, well, maybe not countless, as I have been counting them, but a hell of a lot of fruit trees, mostly huge, mature things. And around us, the vast majority of those in the open countryside are perry pear trees.

So this is a fairly common sight across the region where I live. You might find:

- solitary trees along the field tracks,

- remains of avenues of trees along roads,

- scattered remains of meadow orchards,

- or even rows or single trees in the middle of tillage.

Having a border collie of course meant a lot more walking than I would have been bothered with before, and this brought me into closer contact with trees I’d noticed from the road but had never been inclined to investigate on my own.

The further Anu and I walked, the more perry pear trees we were finding, off the beaten trail, buried in hedgerows and small stands of trees, and it ended up being a standing side-quest: to go for a walk where we’d never been before and find more new pear trees to add to our map.

Incidentally, this is also what dragged me into pomology, as I really wanted to be able to identify what these trees were.

A few example: this little set was of course easy to spot, and we call them the seven sisters – all the pear tree locations get names so we know where to meet when harvesting. Here we have a Vicar of Wickfield, a Schweizer Wasserbirne, Gelbmöstler, Luxemburger Mostbirne, two Grüne Jagdbirne, the most unpleasant pears I have ever tasted by far, and the last one I have not been able to ID yet. But we’ve been allowed to use these pears for the past four seasons.

Maybe an example of an unexpected discovery: a few years ago, during April when the pear trees blossom, we were walking along a road I’d walked I don’t know how many times, but this time noticed patches of white in the treeline on the ridge ahead.

And of course they were pear trees, 14 of them in total, fine big trees that once formed an avenue along a disused road that was marked on a map from 1870. Totally overgrown, I hadn’t noticed the forms of the pear trees until the blossom gave them away. Actually, after that I bought a drone to make the pear hunt even easier!

I still haven’t IDed them all, but we are allowed to use the 5 trees that are free-standing at one end. Brunnenbirne and Luxemburger Mostbirne.

But I guess you get the point, there are lots of pear trees around us. But looking at these 100s of perry pear trees, the question itching at the back of my mind was always – why the hell are there so many of them, and why is nobody is using all this fruit for something?

Some of you are probably thinking it’s pretty bloody obvious, they’re perry pear trees so they were used to make perry. And yes, you’d be right. Or at least partially right. There’s a lot more to the perry pear culture of central Europe than we might think at first glance.

Searching through archives and reading farming handbooks from the early 1800s, I was surprised to learn that perry pears were a staple for farming families at the time. They were used as an animal feed, as the books said feeding pigs with a mix of acorns and perry pears in autumn would fatten them up quicker than on acorns alone.

Perry pears were dried to be used as source of carbohydrates for humans and also as animal feed throughout the year.

They were also pressed, sometimes together with plums, and the juice boiled for up to 24 hours in huge copper pots over a wood fire to make a thick syrup that would last all year as a sugar source for baking or even as a spread.

But of course they were also pressed to make drinks. They don’t call them Mostbirnen for nothing, because Mostbirne means a pear for making Most, or perry.

* * *

But I’m getting ahead of myself. Let’s step back a little.

When I started making cider, it was with zero knowledge of any of this, or the larger cultural traditions that I’d accidentally fallen into. But as I started gathering and restoring all that old cider making equipment from surrounding villages, it was clear that I was picking up pieces of something…bigger that had been left behind.

And then while I was pressing in the front yard, elderly residents of our village would stop by for a chat and they told me that almost every farm in the village used to make their own cider. Or Moscht, as it is called in our local dialect. Beer was only for Sunday as it was too expensive.

But even more amazing was being told that I was directly continuing something that had been carried out – possibly for a couple of centuries – in our very own front yard, as in the past, people used to bring their fruit to our barn to get pressed. The lady next door told me how as a child she was sent over with a bucket to collect Süßmost, or apple juice straight from the press. It was then that I realised that the small cellar in our barn was probably a cider cellar, evidenced by the oak beams running along the walls that once supported barrels.

That felt… well, it felt almost like destiny!

But the fact that nearly every farm made their own cider went some way to explain why there were so many fruit trees in the landscape surrounding the village, in fact the entire region.

So given that context, there was certainly a broader German cider culture that I had missed, and – as I was to slowly piece together – a perry culture that had been all but forgotten.

* * *

When we think of Germany and cider, what is the first word most of us would think about? Feel free to shout some answers, but polite ones please!

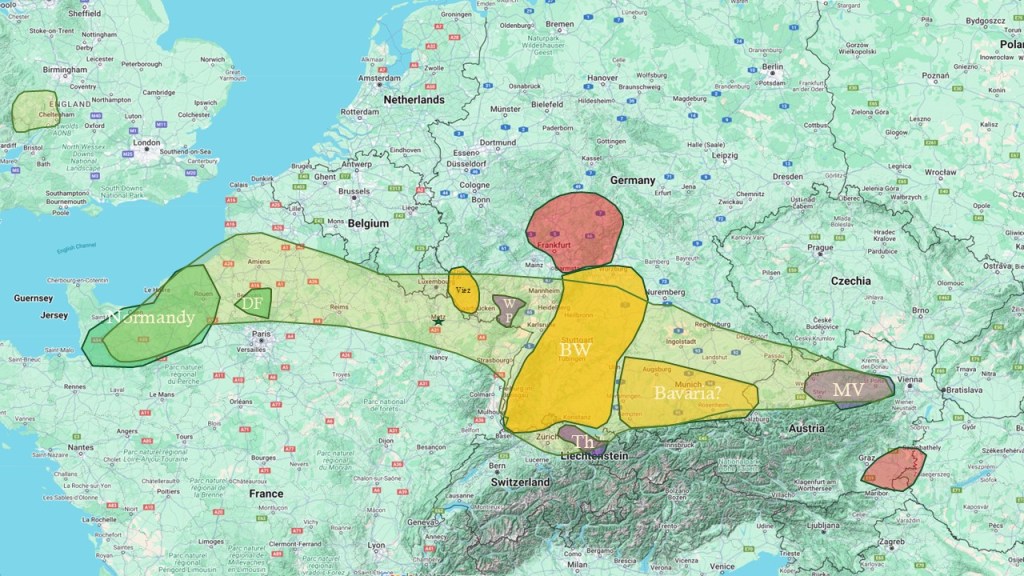

Apfelwein is, I think, the usual answer from people who have even the slightest interest in world cider. And of course, when we think of Apfelwein, we associate that with Frankfurt, and marvel at this enclave of cider-making in Germany.

Here, they were making Apfelwein, which they locally call Ebbelwoi, for centuries. By the end of the 19th Century, Frankfurt was one of the largest, most technically advanced centres of cider production in the world. The cideries were so big, in 1903, an Agent of the US Department of Agriculture described them as cider factories.

But it would be fair to say that Frankfurt’s Apfelwein is the most well-known of the German cider traditions only because it is was here where it best survived. But there are more.

Some 90 miles west of Frankfurt is the ancient Roman city of Trier, sitting on the Mosel, right in prime winemaking territory, and this city is an epicentre for the Viez cider tradition, which spreads southwards along the eastern regions of Luxembourg and into the tiny state of the Saarland.

Viez stayed more agricultural than Frankfurt’s Apfelwein, so is traditionally less, well, less refined, shall we say, than what we get from Frankfurt. But like Apfelwein, Viez is characterised by a sharpness, sometimes quite extreme, but modern makers seem to be toning this down a little.

I should note that both Apfelwein and Viez were recently granted UNESCO status of intangible cultural heritage, so quite a win for these regional cider cultures.

Then over to Baden-Württemberg, where I live, which was once the second-largest cider producing regions of Germany, especially the Swabian region surrounding Stuttgart, just an hour or so south of where I live. Here, the extensive meadow orchards were famous and still today, this area boasts probably the highest concentration of traditional meadow orchards in the world.

In Baden-Württemberg, and indeed in pretty much all of southern Germany, cider is simply called Most.

Actually, in Austria and Switzerland it is also called Most, so by population, this is probably the most common name for cider in the German language

Confusingly, perry is also called Most, but that will usually get a prefix to make it Birnen-Most.

The Most tradition of Baden-Württemberg is interesting, as for a really traditional Most perry pears would be mixed in with the apples, maybe about 10 to 20% of the volume.

The idea was that the tannins from the pears would help clarify the Most, but also the pears would offset the acidity found in the apples being used.

But those pears were also used to make perry, and this is relatively well documented in old literature, with the Champagner Bratbirne being symbolic of the perry tradition that used to hold sway in the Swabian region.

Actually, I just mentioned the tradition was to add some pears to the cider but conversely, old texts recommended adding a portion of acidic apples to the perries, to increase the acidity and help them keep longer.

Though perry all but vanished from Germany’s drinks tradition, the amount of perry pear trees you find in Baden-Württemberg is pretty phenomenal, and when I’m riding a bus or train through the countryside it’s a wonder I don’t have whiplash admiring them all. So we know it was definitely made across Baden-Württemberg.

But there are also wonderful hints that it was also made across the border, in Bavaria, where perry was apparently once the true drink of the peasantry. This goes back to the 13th Century, and a song I found from Austria that basically implied that Bavarian farmers were savages because they drank perry. So we can probably add southern Bavaria to the map of former perry regions.

As always, when researching cider and perry in central Europe, we are only getting glimpses, as unlike beer and wine, it was not taxed and was kept in the purview of the farmers, so far fewer records were kept. So finding medieval songs that either decry or praise perry is like finding gold!

But staying with perry, we can prove that it was made elsewhere in Germany.

Just across the Rhine Valley from Baden-Würtemberg is the small state of Rheinland Pfalz, today, best known for wines.

But in the wild countryside of the Westpfalz, where grapes won’t grow, there is an area that for centuries was known for its perry and ill-tasting pears. There, perry was called Beerewei, or even more colloquially, Beerebumbes, and it was an integral part of the culture there, as were the perry pears themselves. This may have been one of the last real strongholds of living German perry culture, as the making of perry continued at least up to the 1950s in this region.

Perry was also quite a thing in the region around Trier, up where the Viez is, and enough of it was being made in the 18th century, that the city started taxing perry being brought into the city, as it was competing with wine.

While we are on the topic of perry, we must take a glance over to Austria and Switzerland, as their influence on central European perry culture just cannot be overstated.

In Austria, the Mostviertel is a region so synonymous with perry that it was literally named after the drink, so the Mostviertel was the literally the perry quarter of the country. There they had considerable meadow orchards, certainly going back to Medieval times, but after the 30 years war, in order to rebuild food supplies, newlyweds were required to plant fruit trees by their houses, a law which stayed on the books till the 18th Century. And even then, in 1752 the Empress ordered that avenues of pear trees should be planted along all new imperial roads.

So the Austrians have a really proud history of planting especially perry pears and making perry, and we have them to thank for a huge number of pear varieties, many of which spread throughout central Europe.

I should note that I only recently found out that the Strian region of Austria also has a cider tradition, so I’m putting a blob on the map for there too.

Then to Switzerland, one of my favourite topics. Switzerland was once one of the jewels of fruit growing in Europe. Such was the amount of fruit trees in the cantons of Thurgau and St Gallen, sitting just above Lake Constance, that the entire region was sometimes simply referred to as the Obstwälder, the fruit woods. In Spring, people travelled for miles just to see the entire landscape turn white with the blossom of apple and pear trees. In 1855, German pomologist Eduard Lucas described the Canton of Thurgau as “one large orchard.”

But more importantly for us, Thurgau and St. Gallen were once celebrated for making some of the best, if not the best perry in the world. At least that was according to Englishman Dr. John Pell in the mid-1600s, later reported by John Evelyn who wrote the first British Pomona in 1664. Of the Swiss perry, John Worledge later wrote that the so-called “Turgovian Pear” made the most superlative perry the world had ever tasted.

The Swiss had a perry tradition that we can document from at least the 13th through to the mid-19th Century. That’s at least 700 years of slow and careful selection of varieties that suited their landscape, making the best perries ever.

The list of Swiss perry pear varieties is huge, and though they have probably lost half of the varieties they once had, the contribution that Switzerland has made to the European perry heritage is considerable.

I need to check with Rachel and Adam, but as I recall, Babycham once used pear concentrate from Switzerland, I think the Gelbmöstler and Schweizer Wasserbirne varieties.

But now Perry is essentially extinct in what was once what I consider to be its spiritual home.

So this is my working theory, that this was a perry zone that once spanned Europe, and that the types of pears used to make perry across this whole region – so, all tannin-led – shared a lot more in common than the types of apples used to made cider across the same region.

I think perry is the true drink that bound Europe together!

I should point out that I am a trained cartographer, and this is quite possibly one of the worst maps I’ve ever made…

You can read more about these lost Central European perry traditions in Adam’s fantastic book, which I am sure you already have. If you don’t, you can probably address your error today.

But if you are a glutton for punishment and want excruciating detail, you can read some of my deep dive research articles up on Cider Review.

*

I could go on, and on and on, but suffice to say that in southern Germany and parts of neighbouring Austria and Switzerland, fermenting apple and pear juice was once a fundamental part of country life. Sure, it waxed and waned as wars and pestilence took their toll on the farming population, but it remained a constant of rural life until relatively recently. Cider and perry WERE the drinks of the people.

So it kind of ironic that it was a big city, a financial capital of Europe, where the German cider tradition was best preserved into modern times. And tragic that German perry culture almost vanished entirely.

We have to ask: why? Why were we only left with hints, despite the fact that some parts of the country are still blessed with a fairly sizable population of old fruit trees, and in particular perry pear trees, that are simply not being used.

* * *

The two word version of the root cause is probably just “modern life”.

On the one side, the making of perry or cider is a task that takes time, so when convenience products became more accessible for the agricultural community, these old ways simply fell by the wayside.

But of course, agriculture itself was also changing.

Across Europe, while farming in general was being modernised, so too was fruit growing. The trend became consolidation, so instead of having trees as an integral part of the broader farming landscape, they were concentrated into specialised spaces with denser planting and generally smaller forms of tree. So what we would think of as orchards today, with half-standards at most, and eventually more bush forms.

And why? Because across the entire continent there was a move to increase the size of field systems. From the middle of the last Century, tractors were becoming more affordable for regular farmers, so of course the trend was to make fields bigger, get more specialised, ever wider equipment that made farming more efficient.

So, many of the trees that once dotted the landscape, lining boundaries and tracks, were simply in the way. And they were destroyed.

This is by no means a modern phenomenon.

In Germany, from the 1950s there was a set of land reforms, usually enacted at the county level, called the Flurbereinigung, or land consolidation. This was a process whereby the generally small plots of land used till then – a hangover going back to the medieval open field system – were joined up, sometimes swapped between farmers, with new field tracks laid, all to make fields bigger and more efficient.

In a horrible twist of fate, our orchard is a result of these actions. Though trees were being removed from the broader landscape, farmers still needed apples to make heir Most. Around our village, for example, two areas were chosen for denser planting of half-standard trees in 1958. 5 metres between the rows, 5 metres between the trees, quite different to the more open system they had been used to. This meant that the trees could be sprayed en masse by co-ops and the like, which makes sense when the prevalent teachings were that you must spray to get a decent crop.

This pattern of clearance and, if lucky, consolidatin was repeated across Germany from the 1950s on, and is still going on today in some areas.

Our neighbouring village of Oberschefflenz is having a second or maybe third round of it right now. And in the process of widening a narrow access road last year, six of the remaining old perry pear trees on one side of a former pear tree Avenue were cut down. And just last week, another two were cut down where an access road is to be widened. Theoretically they must be replaced, but let’s see.

All told, we don’t know exactly how many trees were destroyed across Germany during this period of change, but a couple of weeks ago I got figures that estimated that in the 1950s to early 60’s, Germany had 3.7 million acres under traditional meadow orchards. That was an estimated 120 million fruit trees. By 2017 it was down to three-quarters of a million acres, estimated around 24 million trees. That is an incredible 80% loss of habitat and genetic diversity within 70 years.

In Switzerland, a much smaller country, similar actions took place, but planned at a national level, and with some other justifications given for doing so. In that case, they had started with an estimated 15 million trees in 1950. By 1975, in a concerted and sustained effort, they had obliterated 11 million from the landscape.

There are lots of photos and videos of this campaign, which are simply horrific for the likes of us to watch. But the end result was that Switzerland’s almost Millenium-long perry tradition doesn’t even reckon in the cultural memory these days, it has been totally forgotten. Anyone making perry there now is reinventing a lost heritage.

Switzerland is a bitter lesson on the consequences of wiping out your orchards, as it totally changed the landscape and even the microclimate there. But by the time people complained it was too late.

Though next week I am shipping a pallet of perry to Zürich, so at least it left a gap in the market!

If you’d like to know more about what drove this act of self destruction, you can search for the Swiss Tree Murder, as it came to be known, up on Cider Review.

Today, in the German-speaking regions, the remnants of these fruit tree landscape features are referred to as Streuobst, literally translated that would mean scattered fruit. And they sit in Streuobstwiesen, or scattered fruit meadows. These words describe the way these large, usually full standard, or Hochstamm trees, are essentially scattered across traditional meadows.

And this word Streuobst is used a LOT in recent years, whether it is new cideries, or juice makers, distillers… anything… highlighting that they use Streuobst is presented as a sign of quality. Sometimes I think too much reliance it put on this, as it isn’t always a guarantee that the end product is good, but it’s nice to know that these traditional growing methods and habitats are being supported.

And funnily enough, when we use some research tools to look at the usage of the word Streuobst in historic literature, it is clear the term really only became popular in the 1950s, coinciding with the massive changes that the European agricultural landscape underwent at that time. In fact, one source says the term originated in Switzerland. So it was originally a derogatory term, disparaging the apparent chaos and inefficiency of this growing method at a time when order and efficiency was driving new methods of agriculture.

And now we celebrate the untidy Streuobst, because it is what we have left.

And the cultural traditions that these trees once fed?

The drying of pears, the making of pear syrup, the use of perry pears as animal feed, all just became unnecessary.

And as for cider and perry, for the most part, it just didn’t fit into modern agricultural life, so apart from a few centres, like Frankfurt, Trier and the area around Stuttgart, it slowly disappeared.

This paints a pretty grim picture, and yes, it is! But if you drive through southern Germany, and especially the region around Stuttgart, you will be awestruck by the amount of fruit trees in the landscape. All those photos I showed you, that’s what it looks like today and when I have cidermakers visiting from other countries, they often remark on the amount of fruit trees they have passed on the way.

In 2015 Baden-Württemberg had 222,000 acres of meadow orchard, estimated 7.2 million trees, almost a third of Germany’s total. But when you know the history, it beggars belief that there used to be more… Vastly more!

But the good news is that Streuobstwiesen, the remnants of those old silvopasture systems, and the new ones increasingly being planted by dedicated individuals, are now protected by law.

And from the cider culture perspective, I get the impression there has been a slow reawakening, as you see more small cideries popping up, and younger people getting interested in reviving old traditions, and making tasty, natural drinks.

* * *

Nevertheless, there is still the issue of a declining population of mature fruit trees and the erosion of the cultural landscape. And that’s where we decided that our tiny little operation should try to make a difference, not just preserving what’s there, but to try to restore something.

One of my wife’s favourite concepts is that you cannot protect something you do not know, so since we started making perry the phrase we have used is conservation through use.

Essentially, it is through making perry that we try to raise awareness of the perry pear trees surrounding our village. And to show the farmers the breadth of variety to be found, despite every single farmer thinking they are all the one same variety, Schweizer Wasserbirne!

By making single variety perries, we can explore what makes each perry pear so unique, and the huge spectrum of old pear trees surrounding us provides a really broad pallet to choose from. So if I can give a farmer a bottle that contains something made from one of their trees, I hope it means they are so impressed that they will leave the tree in peace, and not just see them as an obstacle to their ploughs.

And there are no better examples of precisely this kind of conservation through use, and raising of awareness than Ross-on-Wye’s Flakey Bark perries, or Tom Oliver’s infrequent Coppy perry. Who the hell would have even heard of these two rare varieties if it wasn’t for some idiot makers taking a punt on making something from such idiosyncratic fruit?

In Germany, some of you may have heard of Jörg Geiger from near Stuttgart. He is probably the most famous cider and perry maker in Germany, and he worked to promote and preserve the cultural importance of the Champagner Bratbirne, that local variety I already mentioned, that he also uses to make single variety perries.

He gained a lot of publicity from it, as the Champagneois really didn’t like him using the word Champagne on the label, so they took him to court, all the way to the European level. And of course he lost, the name of the variety is only allowed on the back label. But it’s still a good story and has cemented the Champagner Bratbirne in the modern perry folklore. And that is good, because names have a power.

So we try to do the same, in our small way. We now have permission to harvest from over 100 big old pear trees scattered over a wide area, and perry now accounts for at least half of our annual production. I often say if I could just make perry I’d be happy, and that is completely true.

But though I think making use of these trees is helpful in some small way, I wanted to do more, and it was an innocent query about how to get Flakey Bark scions that started me down yet another path.

I was just amazed that a perry was being made from such a rare variety, so at the end of 2020, when planning grafting for the following year I thought maybe I could help the conservation effort in some small way. So I asked Albert about how to get my paws on some Flakey Bark scions, and he quite rightly pointed me to Jim Chapman, former manager at the National Perry Pear Centre.

What began as a simple question developed into two things: one was a two year rabbit hole of research, triggered by Jim asking me: “have you ever heard of the Turgovian Pear, it might be German or Swiss”. And the other was a slightly larger grafting and planting project than I had ever intended.

While exchanging mails with Jim, the initial request for some Flakey Bark scions turned into an academic exchange, and the list of pear varieties I wanted grew to include all those originally listed in Evelyn’s Pomona – or at least the ones that hadn’t gone extinct. I just wanted them because of their historical significance!

And then I thought, well, while I’m at it, I should really graft some special varieties from Central Europe too. So I selected a whole slew of varieties, some of which I had already been using to make perry, and others sought out for their rarity or cultural significance. With some, I literally said to the collection owner, send me scions of any pear you think desperately needs help to survive, so I sometimes ended up with some endangered dessert pears, but that’s fine by me!

The following years of grafting saw almost nothing but perry pears, with even more English varieties being added, this time whittled out of Luckwill and Pollard’s 1963 book, Perry Pears, selecting any variety that was described as being very good or excellent for perry. I also managed to get my hands on some French classics and, three years after starting the search for the Turgovian Pear, I finally got scions from Switzerland of the Bergler pear, which is its true name.

But of course, when you start grafting hundreds of trees, you eventually have the challenge of where to plant them, and that was a real problem, especially when we needed a safe, permanent home for them, and we needed to pay for it.

And so was born the idea of the International Perry Pear Project. A very grand title for a fairly small project.

*

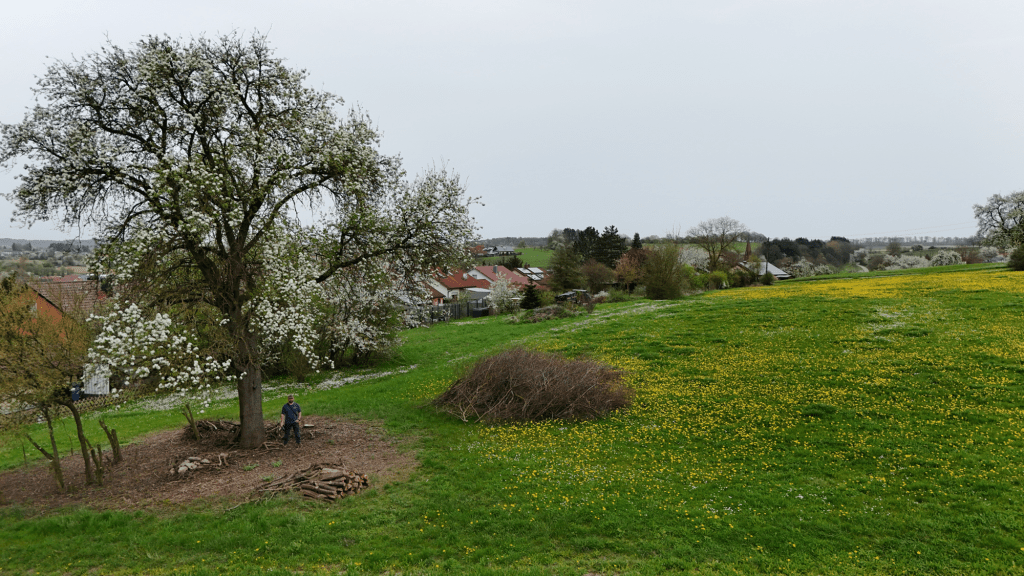

So we already had that 1.5 acres of orchard with mature apple trees, but we needed a new site to create a traditional meadow orchard dedicated to perry pears. To ensure the longevity of the trees and remove the risk of them someday being ripped out by other farmers, we preferred to own a plot of land rather than leasing it, and thanks to Gerd Hauck, our local forester, we eventually found someone willing to sell a small field, about 1.5 acres that had been under tillage.

But funding the purchase was another challenge, despite the relative cheapness of land in our area.

State funding or grants for planting trees is a thing in Germany and, certainly as a farmer, you can also apply for grants to take care of existing full standard trees. But it’s a surprisingly difficult topic in our area, as there is also a ridiculous conflict with a partridge protection project – apparently partridges do not like pear trees despite what the Christmas carol says! And that meant we couldn’t get the normal grants that would help plant new trees.

But private sponsorship, as a form of funding, came up in discussions with friends, and I tested the waters on Twitter, before it turned into a total shithole, and the response was pretty positive. So that’s what we did.

We came up with a sponsorship scheme, where people could sponsor a tree, selecting a variety if they wanted, which including 100 square metres of meadow around each tree. As 48 trees would fit on the plot, a one-off fee of €150 Euro sponsorship per tree would help cover the costs of the land.

Through social media, we sold almost all 48 sponsorship slots within two weeks, which was frankly incredible and very moving.

Although most sponsors knew of me and my tree activities for some years, there was a lot of international interest from cider and perry fans, and some people who just wanted to invest in something that seemed positive and worthwhile.

*

The sponsorship funding helped us to acquire the plot of land, but it also helped fund the purchase of a regionally certified flowering meadow mix, which is pretty expensive. But I considered this an essential part of the project, as the meadow is the canvas on which it is all based, and until the trees are mature, a vital component in providing a biotope

The meadow was sown in April 2022 under ideal conditions, and although it got off to a good start, drought conditions later that year meant that it didn’t develop as well as we hoped. But in 2023 it really came to life, with a constant show of everchanging blossom, a real oasis in the monocultures surrounding it. I remember walking up and seeing the whole meadow covered with ox-eye daisies for the first time, and it was incredibly emotional, and a huge relief, to feel we’d actually succeeded.

2024 was a relatively damp year of consolidation and giving it time to fill gaps. We had intentionally over-sown the herbs and flowers component, as grass would come itself, and now we see that happening, turning into a meadow proper, as we mowed and made usable hay for the first time last year. But I know that over the next few years it will need to be managed to help it develop further and really become something stable for the future.

In the next year or two we will add some additional features, like a sandarium or two for bees and lizards to use, dead wood and stone piles for creatures to hide in, and nesting boxes and lacewing houses as trees get bigger.

*

And the trees themselves, we finally planted them early last year. And what a great year it was for planting trees, as we had a good supply of rain, totally bucking the trend from the previous six years, so they all survived the first year.

We planted 10 metres between the rows, and 10 metres between the trees, and the planting order is according to harvest time, so when we can eventually harvest, we can move from one end to the other as the harvest times move along.

And each tree is of course protected from deer and hare, which are a real problem where we are, and mulched with a thick layer of wood chips from broadleaved trees, not conifer bark, to help keep in moisture and also dissuade voles, as they don’t seem to like tunnelling under that loose material.

Each tree also got a little earwig hotel, as they are supposed to help with pest control, and this doubles as a cute label.

Though I have to say we were warned not to label trees, as there have been tree rustling events in the region, with trees being stolen out from the ground soon after planting if they were advertised somewhere!

Oh, and we also installed perches so the local kestrels and red kites would have somewhere to sit, and not land of the young trees, breaking the leader.

*

Without our sponsors, none of this would have been easy, or even possible. But there are disadvantages to having sponsors, the biggest being a constant feeling of not doing enough for them!

But orchards, and especially perry pear trees, take time to grow, and I think our sponsors are very patient and understanding of that, aren’t you? I think there’s more than a few in the audience today!

As most of our sponsors are in Ireland, the UK, across Germany and even a couple in North America, we use an occasional newsletter (in both English and German) to keep them informed on milestones and general progress, including video updates of me blabbing on unscripted.

Also, and I have been extremely slow to do this, as I wanted to be sure the trees were surviving, is that each sponsor gets a certificate, and a link to a map showing the precise location of the trees they sponsored. I’d like to keep a photo journal of the trees so they can see the progress over the years.

And if I live long enough, someday I hope to make a perry blend and share that with the sponsors.

*

But hot off the press, and in spectacularly good timing, last Saturday we began planting phase 2 of the project!

This time, on an existing meadow, though one that had been intensively managed – so lots of slurry and lots of mowing. This is a 1.5 acre site owned by the local council, which I signed a lease for at the end of 2023.

However, I recently made a proposal to the new Mayor, and just last Monday, the council voted to approve it, which means they will fund the work on the orchard for at least the next 25 years.

The deal is that they can apply for eco-points for the work I am doing in improving he environmental value of the meadow, essentially a kind of eco-offset mechanism that they need to offset, let’s say ‘less green things’ they may need to do elsewhere in the village. So instead of me applying for and generating these points and selling them to the council for vast sums of money, they will apply themselves, but I can invoice them for the trees, materials and for my time maintaining them. Essentially, I am the project manager, so I get to steer what direction the orchard goes in, but I can call on the council for help with machines and materials, so it just lifts a lot of the pressure.

For me it was more important to get the trees into the ground, and this eco-point system guarantees that they MUST stay there by law. So they have a safe home, so I’m really happy with this!

The trees on this site are on a variety of rootstocks, so this will be an interesting experiment to see how certain varieties behave on different rootstocks.

But best of all, there is already a wonderful mature perry pear tree in the corner of the meadow, a Geddelsbacher Mostbirne, which I hope to use to make a single variety perry this year.

*

Looking to the future, I know we will never roll back time and regain the benefits that a landscape filled with trees can do for our climate and local biosphere, but I firmly believe that every little helps, and it is at the grassroots level that we, as individuals, can often affect the most change.

I often tell people; I am getting nothing out of these orchards. They will take so long to really mature, that I don’t expect to ever harvest much from them. Pear for the heirs as they say, so I make sure locals know that I am planting these for the good of the village and our environment too. It’s not just a valuable gene bank of rare varieties, but a new and developing biotope that I hope will be a haven for wildlife.

And the response is usually overwhelmingly positive.

And we still have about 300 trees in our two small nurseries, looking for a home.

We did have a lease for a site for Phase 3, intending to run it exactly as Phase 2, but the council had to reclaim that site for a possible school extension. But the mayor assures me he will be looking for other suitable sites.

And as we will be formally inducted as partners in the Neckartal-Odenwald Nature Park next week, with a ceremony on our perry orchard attended by some big-wig political dignitaries, I think our new Mayor will be even more willing to support a broader project, so maybe those 300 trees will find a home.

I will keep pushing our local council to do anything possible to get fruit tree back into the landscape, despite the partridges!

* * *

I must stress, we are not the only ones doing these kinds of actions. Well, we might be the only ones in Germany planting just perry pears, and we are probably the only ones with a pan-European perry culture focus. But there are many small groups and individuals planting new orchards across Germany, and looking at social media, there seems to be a growing number of organisations that support such activities, doing great work at a local or regional level.

I am a member of one such group, Hochstamm Deutschland, which promotes several initiatives to help get fairer prices and promote produce from traditional meadow orchards, mostly fresh fruit and juice, but also cider. And as it happens, the current chair of this organisation, Ole Klann, is in the audience. Can you please stand up Ole, so people can see who you are?

Ole is also a cidermaker, which is of course why he’s here, and he and Josh from Nordapple are also planting new meadow orchards, with a focus on apples, but way up in the north of Germany, an area not so traditionally associated with cider.

* * *

I’d better stop talking soon…

Like most people who get into cidermaking as a side-project these days, I am under no illusion of getting rich from it.

I am in a privileged position in that I have a full-time “normal” job that pays the bills and can do my cidermaking and orcharding activities in what spare time I have.

I don’t have to do it, and I definitely couldn’t live off it at the current scale, certainly not given the current German market.

However, it’s my perry making that has activated this desire to try to preserve what we have left of this incredible cultural landscape surrounding us, and it is our cider and perry making that helps fund some of our attempts to bring back small parts of it, so something will still be there for future generations.

I’d like to leave you with a thought from one of my heroes of sorts, astronomer Carl Sagan, whose words have inspired the naming of many of our creations. In Cosmos: A Personal Voyage, he said the following about trees.

“The human species grew up in and around [trees]. We have a natural affinity for [them].

Trees harvest sunlight; they compete for the sun’s favours, pushing and shoving for sunlight, but with grace and astonishing slowness.

There are so many plants on the Earth that there’s a danger of thinking them trivial, of losing sight of the subtlety and efficiency of their design. They are great and beautiful machines, powered by sunlight, taking in water from the ground and carbon dioxide from the air, and converting them into food for their use and ours.”

As cider and perry makers, we are blessed with the honour of working directly with the fruit of these beautiful machines, and so, we are uniquely placed as stewards to speak for them. Let’s try to continue to do so.

Thank you.

Cover image: A pear tree in blossom amongst fields of grain. Photo: Barry Masterson.

Discover more from Cider Review

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Superb Barry.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Tom!

LikeLike

Thanks a fascinating talk – i wondered why you had posted before about earwig hotels – now i know. April sunshine here in Monmouth and the perry blossom is announcing the start of the season with a great show. The apples are just beginning to leaf. Hopefully a better year than 2024

LikeLiked by 1 person

thank you!

yeah, fingers crossed. Sunny here now, but bitterly cold with a persistent east wind. Hope it warms up for the pollinators by the time the pears blossom!

LikeLike

Pingback: Jörg Geiger, the vanguard of non-alcoholic cider and perry | Cider Review

Pingback: Editorial: Perry Is Not Dead. | Cider Review

Pingback: Modern Mythbusting: The Cyder Controversi | Cider Review