The idea of Made Wine as a duty classification is a fascinating, but also infuriating subject for both maker and drinker alike. The simple act of even dipping a hop cone into a cider is enough to magically transform it into a higher tax class and be designated made wine. Well, at least till the August 2023 duty reforms in the UK, where it is now just called “other”, but I believe the class still exists in Ireland. But the fact remains, adding even a basic natural flavouring ingredient to a full juice cider or perry immediately changes the tax classification. Even adding a portion of fresh-pressed juice from another pomme fruit, the quince, will mean a higher tax band. But where did this come from? What does it mean to be a made wine?

When writing last year about the traditional and historical additions of fruit for both technical and flavouring reasons, I had come across some recipes for making imitation wines that I stashed away with the intention of translating and simply publishing them out of curiosity. But just a few months ago I came across another text that changed the character of these recipes, cementing in my mind what “made wine” really referred to. Basically, making fake or imitation wines by using cider and perry as a base, or using cheap wines and making additions to give the impression they are something more expensive than they are.

Apparently, England, and especially London, was particularly prone to this kind of activity. England, not generally a wine producing region by the 1600s, imported masses of wine from all over Europe, and wine traders saw opportunities to make some easy money by either cutting wines with locally available cider and perry, or by mixing up ingredients with a cider to approximate popular, more expensive wines.

In 1845, German physician, writer, translator and veterinarian, Friedrich Duttenhofer, dedicated an entire chapter in his book on fermented drinks complaining about the forging of wines, an action that he most definitely disapproved of. It’s worth quoting Duttenhofer to set the scene.

“Although it is a recognised fact that wine must be regarded more as an object of luxury than as a necessary necessity of life, it is nevertheless one of those luxuries which, when used moderately, serve to amuse social life, to which every man has the right to lay claim. It is therefore highly to be regretted that a beverage which is generally preferred and used by our middle and higher classes is so frequently subject to adulteration that he who wishes to procure genuine and pure wine must possess much knowledge and experience; indeed, in ordinary cases this is hardly possible, especially in small quantities, without the application of precautions with which few are familiar. Those people, however, who engage in fraudulent practices in relation to wine, in spite of the known danger which is connected with the drinking of such beverages for health, do not allow themselves to be deterred by the consciousness of the harm which they do to society; but there can be no doubt that even if all adulterants are not equally very harmful, most of them by no means have an indifferent effect. Everyone should therefore be on his guard in this respect and bear in mind that instead of a healthy drink he often drinks a slow-acting poison, but in any case, in very many cases he must pay the price of the first quality for a drink of inferior quality.

The extent to which the adulteration of wine is practised in Great Britain, and especially in London, would border on the incredible, if the testimony of good authorities did not prove it; but this is an evil which can scarcely be remedied, unless the public be very accurately instructed in this respect. As there is scarcely any wine growing in England, there are comparatively few people who are acquainted with the true taste and other qualities of a genuine wine, and therefore it is all the easier to practise fraud. The manufacture of adulterated wines has become a regular and extensive trade in London, and those who are engaged in it know how to practise it with so much skill that they imitate foreign wines of almost every kind artificially enough to deceive even good wine connoisseurs. Lest it be supposed that this assertion is erroneous or exaggerated, it may be mentioned here that the practices of wine adulteration are so well known and general that there are books of their own in which the most approved recipes in this respect are given, works to which we largely owe our knowledge in this direction, and whose lively sales bear witness enough to their use. We must, however, say that we do not wish to vouch for the correctness of these adulterations, nor do we wish to claim that they exclusively describe the methods used at present. The very fact that they have been published indicates that they are used to a greater or lesser extent; but all the modifications used by the various wine adulterators will probably never be discovered.” (Duttenhofer 1845).

Fitting to his role as a physician, he goes on at length about the dangers of adding lead acetate, which was apparently common as it also sweetened the wines, though by this time was well known to be most definitely poisonous. But he does also list technical additions that are beneficial, for the purposes of improving or clearing a wine, for example, or the blending of wines:

“If these tricks were confined to the blending of pure wines, lesser and better, it would hardly be worth mentioning, for such blending of wine is frequently practised, and, if done with proper expertise, serves to improve the wine; but the regulations made public in this respect, which give us a glimpse into the secrets of the wine adulterators, prove to us that actual fraud is involved”.

Nevertheless, Duttenhofer goes on to provide detailed recipes for faking Port, Claret and other wines, usually based on cheaper wines, but here is a Port recipe based on finished cider.

“Good cider 45 gallons, brandy 6 gallons, good port eight gallons, ripe sloes two gallons; these are crushed in two gallons of water, the juice squeezed out and added to the other liquid; if the colour is not dark enough, add tincture of red sandalwood. After a few days, this wine can be bottled; a teaspoonful of powdered catechu [tannin from acacia bark as I recall] is then added to each bottle and shaken well into the wine, as this creates a beautiful crust when the wine is usually laid on its side. The end of the catechu is soaked in a strong decoction of Brazilwood, to which a little alum has been added, and this, together with the crust, gives the wine the appearance of age”.

So not just faking the flavour, but also adding to the visual trickery of replicating an aged port!

46 years later, another German author, agriculturist Heinrich Semler, wrote a book called “Complete fruit processing after the experiences by the North American competition”. In it, he has a section on the making of “imitation grape wine” based on cider. Semler, however, had a very different outlook to Duttenhofer, reasoning that if they were simply sold as what they actually were, in essence flavoured or fortified ciders, there would be no harm.

“Cider is often used as a “raw material” for making wine, which is especially true of England, where one is often served “real” Burgundy, sherry or port made from cider with other suitable substances. If these drinks were only sold under their true name, there would be no objection to their existence, for they consist of harmless ingredients, whereas this cannot always be said of the genuine wines mentioned. They are all too often adulterated with substances that are dangerous to health. Since these imitations, if well prepared, taste excellently and are only slightly inferior to the genuine articles, the German fruit growers should at least produce their own wines for their domestic use. The considerable sums which now flow out to France, Spain and Portugal for Burgundy, Sherry and Port could then be reduced a little” (Semler 1895).

He lists ten such recipes which I have translated below, to give a brief example of the kinds of actual made wines that were being made in the 19th Century, and probably well before that.

Burgunderwein

- 40 litres apple juice

- 1 litre blueberry juice

- 5 pounds (2.5kg) squashed raisens

- 3 pounds (1.5kg) brown sugar

- ¼ pound (125g) red Weinstein/Potassium bitartrate/cream of tartar

Pour into a barrel and let the fermentation run its course while constantly topping up with cider. Then clarify with isinglass, add some bitter almond essence, and bottle the wine after a few weeks.

Malagawein

- 40 litres apple juice

- 2 litres sugar syrup

- 5kg crushed raisins

- 500g elderflowers

- 2 litres rectified spirits (neutral alcohol c. 96%)

- 30g Essigäther (Ethyl acetate)

The desired colour can be achieved by adding elderberry or blueberry juice. Otherwise, the process is the same as described above.

Portwein

Add 25kg of crushed raisins to 50 litres of soft water, and leave them for two weeks at a temperature of around 20°C. Then rack the fluid into a barrel, add 4 litres of strong syrup, ½ a pound (250g) cream of tartar and ½ to 1 litre of elderberry of blueberry juice. After four weeks the wine will have cleared and can be bottled.

Sherry

- 50 litres apple juice

- 3 litres neutral alcohol c. 96% vol

- 5g orange blossom water

- 5kg crushed raisins

- 60g cream of tartar from red wine

- 30g ethyl acetate (essigäther)

The process is the same as that described for the Burgundy.

Claretwein

- 50 litres apple juice

- 50g cream of tartar

- 4 litres neutral alcohol c. 96% vol

- 2 litres blackcurrant juice

One can add elderberry juice as desired. The process is the same as that described for the Burgundy.

Or one can mix fully fermented cider with blackcurrant wine (from1 litre juice, 2 litres water and 2 lbs (1kg) of sugar, at the ratio of 9:1.

Bordeaux

- 190 litres cider

- 24 litres cherry juice

- 13 litres rectified alcohol (90%)

- 500g Sève de Médoc [I don’t know what that is]

- 125g Tannin

First dissolve the tannin in hot wine, mix all the ingredients in a barrel that is easily rollable. After a few days the wine can be cleared with egg white (protein).

Madeira

- 112 litres cider

- 3kg sugar

- 3kg aromatic honey

- 8 litres rectified alcohol (96%)

- 8 – 15g hop cones

Let the mixture stand for 14 days then rack off and bottle.

Muskat-Frontignan

- 100 litres cider

- 6kg white candy sugar

- 600g dried, good quality elderflowers

- 10 litres rectified alcohol (96%)

Dissolve the candy sugar in 3 litres of water over a fire, add to this hot solution the elderflowers and allow to cool. Pour the syrup and elderflower mix through a sieve into a barrel, then pour the cider over the flowers in the sieve to extract al the sugars. Stir the mixture well.

Muskat-Lünel (Muscat de Lunel)

- 110 litres cider

- 10kg white candy sugar

- 700g dried, good quality elderflowers

- 12 litres rectified alcohol (96%)

To dissolve the sugar use 5 litres of hot water. Otherwise, the process is as described above.

Alicante

- 85 litres cider

- 13 litres rectified alcohol (96%)

- 8kg fine sugar

- 7 litres water

- 2.5 litres blueberry juice

- Orris root extract – Just enough so as not to dominate.

Dissolve the sugar in the water. The solution is added to a barrel with all the other ingredients, with the orris root extract being added last, as one must be very careful, as the aroma spreads extraordinarily wide in fluids. Too much, and the wine will be spoiled. One should never notice the aroma of the individual ingredients added. If this is the case, the wine imitation has failed.

I would very much like to get my hands on the British instruction books for fakery that Duttenhofer mentioned, but it would seem it was common enough that Semmler’s accounts might be reasonably representative of what was being done in Britain at the time.

So there you are. A user’s guide, of sorts, to making actual made wine, which I assume the tax was established to try and dissuade either as a health protection or more likely to protect the wine trade and make more cash for the Kingdom’s coffers, as that is usually the answer when one asks why a tax was introduced.

Bibliography

Duttenhofer, Friederick M. 1845. Die Gegohrenen Getränke Bier, Wein, Obstmost Und Meth. Stuttgart: Becher und Müller.

Semler, Heinrich. 1895. Die Gesamte Obst Verwertung Nach Den Erfahrungen Durch Die Nordamerikanische Konkurrenz. Wismar: Hinstorff´sche Hofbuchhandlung.

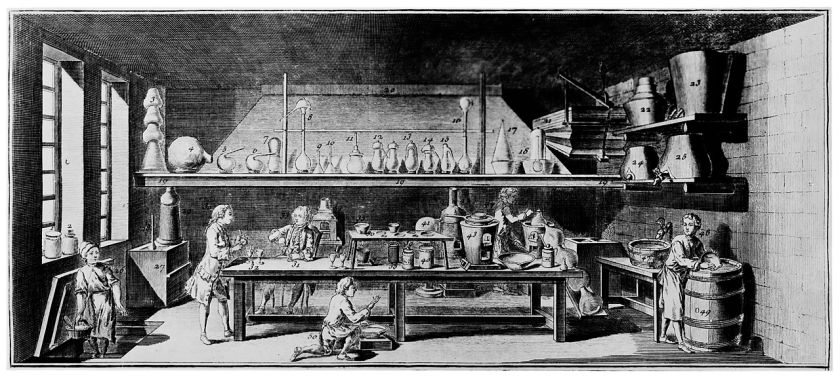

Title image: Chemical laboratory, Paris. 1760. Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0). Source: Wellcome Collection. https://wellcomecollection.org/works/uy4g5b9p

Discover more from Cider Review

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Hi Barry – I think I may have found a few made wine recipes for you. Check out Gervase Markham’s ‘Country Contentments, Or the English Huswife’ (1623) from p. 143 on Google Books (https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Country_Contentments_or_the_English_Husw/N4NmAAAAcAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=made+wines&pg=PA143)

Seems to be a selection of instructions for blending different types of wines and sundry other ingredients in order to ‘improve’ the originals? Not sure if that’s exactly what you’re after, but it might be a useful starting point..?

LikeLike

Hah! Brilliant. A lot of eggs and milk being used there! 😆 But also spotting the use of cloves, ginger and the like, which I’ve used myself based on some early 19th century recipies.

Will have to make a new book of fake wine recipes of our own 😉

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reminds me of the documentary ‘Sour Grapes’ where a guy was counterfeiting wines at the highest level and selling them to Silicon Valley millionaires. Blending $100 bottles to taste like $10000 – a genuine talent and he fooled a lot of supposed ‘experts’ for a long time. Makes you question the actual value of these ‘elite’ wines too…

LikeLike

I’m now wondering if I should diversify my cider business 😀

LikeLike

Pingback: My essential case of perry and cider 2023 | Cider Review

Pingback: Cider Review’s review of the year: 2023 | Cider Review