In my formative drinking years in Ireland, cider was always either a two-litre bottle that we’d swig in a park, or later pints of Magners (or Bulmer’s as it was called in Ireland then), the company that seemed to single-handedly make cider cool again with pint bottles poured into branded pint glasses with ice, so you’d have to top it up again.

It wasn’t until much, much later in life that I realised cider had such a rich tapestry of history to tap into, and that the perception of cider over the centuries has waxed and waned considerably, with a whole gamut of styles and flavours to cater for almost all tastes and pockets.

But every so often on social media there is a kind of kickback against the apparent winification of cider. Some appear to fear this as a kind of erosion of the traditions of cider and argue that cider is cider (and I do agree) and can stand on its own two feet. But is this really something that is happening at a meaningful scale that changes anything? Or is it something that cider has actually lost? What does this idea of winification really mean?

As I always say, when it comes to cider there is almost nothing new under the sun, so let’s see what history has to say on the matter. For convenience I’ll just say cider, but please do read this as including perry as English history, in particular, once had a special place for that wonderful drink as a national wine!

Cider is not wine, but is it A wine?

In terms of how it is made, the processes for making full juice, full strength dry cider is of course pretty much identical to regular, common-or-garden wine. It is the fermented juice of a fruit, which is precisely all that grape wine is. Being in Germany, I probably find it easier to square the idea of cider as a kind of wine, given the standard German name is Apfelwein (apple wine), or Birnenwein (pear wine) for perry. However it must be said that until the mid-1800s, the terms Cider and Cyder appeared much more frequently in German literature. But here, there is a whole universe of Obstweine, or fruit wines, it’s just the grape stuff had the upper hand and received the default shorthand.

While the Romans brought the vines northward, it would seem there were already fermented fruit drinks around the Germanic tribal areas (mulberry wine was one such drink I stumbled across in early accounts), and I daresay further north too. But the distribution and coexistence of wine(s), beer, cider and perry in early central Europe is another fascinating topic that warrants a deeper look, as while the likes of wine and beer were well recorded, often being under the purview of the nobility or the church for tax reasons, cider and perry was usually in the domain of the farmers, and it appears the cultural significance of cider across Europe was not recorded so diligently in the earliest times.

Certainly, throughout history, and especially in the late 17th Century, possibly the golden age of cider in England, it was not at all unusual to compare cider to wine. Indeed, in England cider was explicitly seen as a substitute for wine, as there were difficulties with, and a desire to reduce reliance on imports. John Evelyn expressed that desire in his 1664 Pomona, at a time when this general movement was in its infancy, also encouraging the use of wilding apples that apparently had more wine-like properties.

“Yet since our design of relieving the want of Wine, by a Succedaneum [substitution] of Cider, (as lately improv’d) is a kind of Modern Invention, we may encourage and commend their patience and diligence who endeavour to raise several kinds of Wildings for the tryal of that excellent Liquor, especially since by late experience we have found, that Wildings are the more proper Cider-Fruits, some of them growing more speedily, bearing sooner, more constantly, and in greater abundance in leaner Land, much fuller of juice, and that more masculine, and of a more Winy vigour” (Evelyn 1664).

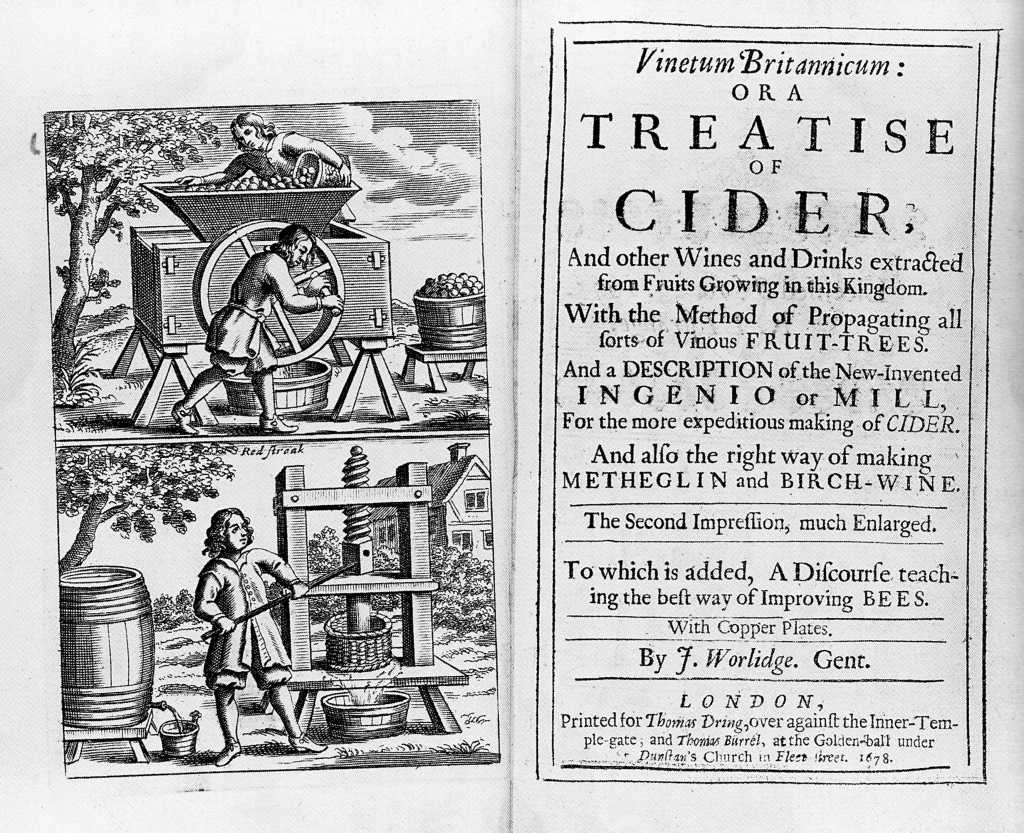

In 1678, John Worlidge, in his Vinetum Brittanicum, argued that cider really is a wine, and if it wasn’t for all the pesky foreign imports and the need to differentiate from them, cider would rightly be called (British) wine, and went so far as to say that orchards are more properly vinyards.

“The name of Cider; if from Sicera, is but a general name for an inebriating or an intoxicating Drink, and may argue their ignorance in those times of any other name than Wine for that Liquor or Juice in the Saxon or Norman Language, either of those Nations being unwilling (it’s probable) to use a British name for so pleasing a Drink, they not affecting the Britains, made use of few of their words. But since that, that Wines have been imported from Foreign parts in great quantities, the English have been forced to make use of the old British name Seider, or Cider, for distinction sake, although the name Vinum may be as proper for the Juice of the Apple as the Grape, if it be derived either from Vi or Vincendo, or quasi Divinum, as one would have it.

Also the vulgar Tradition of the scarcity of Foreign Wines in England, viz. that Sack* which then was Imported for the most part but from Spain, was sold in the Apothecaries Shops as a Cordial Medicine; and the vast increase of Vineyards in France, (Ale and Beer being usual Drinks in Spain and France in Pliny’s time) is an Argument sufficient that the name of Wine might be attributed to our British Cider, and of Vineyards to the places separated for the propagating the Fruit that yields it” (Worlidge 1678).

The comparison of cider with wine was especially strong when it was a particularly good cider, and there was often great pride taken in making a cider that was indistinguishable from its grape-based sister. Indeed, literature suggests it was the English who made the most comparisons, perhaps as they were searching for alternatives to expensive foreign imports, seeking local wines, of which perry was definitely a posterchild in the 17th Century. There are probably hundreds of examples of favourable comparisons to favoured wines of the day. Most especially Canary, Sack, Rhenish, Malaga and Malvasier wines during the 17th and 18th Centuries.

Here is a sprinkle of quotes as a flavour of the types of comments made relating cider to wine:

In part one of my quest for the Turgovian pear, we saw that John Pell had written to Hartlib comparing the Turgovian perry to Muscatel wine: “Not long since one sent me a bottle of liquor whose colour smell & taste enticed me to pronounce it to be as good as muscatel as ever I had tasted. But he that sent it told me it was nothing but Turgowe [Turgovian] wine [perry] ten years old” (Pell, 1658).

“The Underleaf is a Herefordshire Apple of a Rhenish-wine flavour, and may be accounted one of the best of Cider-Apples” (Worlidge 1678).

Hogg and Bull tell us of a letter dated “Bristoll, 20 November, 1691”, from Thomas Wattmore, vintner to Sir Barnabas Scudamore, in which he writes of, I believe, a Redstreak cider: “I bought 50 hogshatts last yeare at Dimmock and they are as rich as new Canary. I cannot sell bad Sider” (Hogg and Bull 1886).

By all accounts, well-made cider was considered fit for a king. Reverend John Beale of Herefordshire, writing in John Evelyn’s Pomona in 1664, reports of King Charles I and his retinue favouring cider above the best of the locally available wines while visiting Hereford:

“I must not prescribe to other palates, by asserting to what degree of perfection good cider may be raised, or to compare it with wines: but when the late King (of blessed memory) came to Hereford in his distress, and such of the Gentry of Worcestershire as were brought thither as prisoners; both King, Nobility, and Gentry, did prefer it before the best wines those parts afforded and to my knowledge that cider had no kind of mixture. Generally all the Gentry of Herefordshire do abhor all mixtures.

Yet if any man have a desire to try conclusions, and by an harmless art to convert Cider into Canary-wine; let the Cider be of the former year, masculine and in full body, yet pleasant and well tasted: into such cider put a spoonful, or so, of the spirit of Clary, it will have so much of the race [terroir] of Canary, as may deceive some who pretend they have discerning palates” (Beale, 1670).

Hugh Stafford, whose 1753 book A Treatise on Cyder-Making was also translated to German, recounts the origin story of the Royal Wilding, and how his friend Woolcombe was seeking a name for his new British wine:

“Mr Woolcombe was not a little pleased with it, and talked of it in all conversations; it created amusement at first, but when time produced an hogshead of it, from raillery it came to seriousness, and everyone from laughter fell to admiration. In the meantime he had thought of a name for his British wine, and as it appeared to be in the original tree a fruit not grafted, it retained the name of a Wilding, and as he thought it superior to all other apples, he gave it the title of Royal Wilding” (Stafford 1753).

The most entertaining accounts tales of blind tastings, where the pride is especially high. And just like today, perhaps a bit of blind tasting was needed to counter the effect of preconceptions and prejudices.

In 1576 (or possibly 1578), Melchior Goldast, in a chapter dedicated to describing the history of perry in his book about ancient authors and the Germanic peoples, described the following scenes from a blind tasting in Nuremburg, Germany, where the Turgovian perry was tasted, and visitors could not distinguish it from wine:

“Not once did I interject, when the foreigners were persuaded by its colour, sweetness, and smell, to drink it [the perry] instead of Malvatico [malvasier wine]. And it happened at Nuremberg, which I am about to mention. Gaffar Schlumpsius, a citizen and merchant of St. Gallen, prepared a banquet no less splendid and laudable. For this purpose, he also called merchants who had explored most of the regions of the Ultramarines [overseas, nothing to do with Warhammer 40K], and also taverns famous for their appreciation of exoteric wines. A tasting of the table is brought at the beginning, the chief of which was holding that boiled perry. He inquired of the guests whether they should judge the wine? When some said it to be akin to Malvaticum, some to Cretan, others to Corinth, another to Corso wines, at last he declared that it was, freed from contention, the Turgovian [perry], and that was born not of strength [or maybe the vine] but in the trees” (Goldast, 1576).

Imitation wines

As already mentioned, the English in particular seemed to have wanted to have wines from their own country to compete with the foreign imports, and cider and perry were the absolute ideal candidates. At one time in the 17th Century there was certainly a desire to see perry production increase to reduce the reliance on, and the sending of money to foreign powers, and sometimes “the enemy”.

Robert Hogg describes some of the background to this in The Apple and Pear as Vintage Fruits, and you get the impression that there was always really expensive cider selling for prices as high as wine (he does go into details of pricing elsewhere in his works), and the less strong stuff for everyday drinking by people working the fields.

“It was not until the end of the 17th Century that the English Orchards began to be much planted. The Civil War with its troubles had passed by: Continental wars prevailed for the most part; and as foreign wines ceased to be introduced, it became an object of national importance—a patriotic duty—to encourage the home production of Cider and Perry in every possible way. Poets and Writers extolled their praise: Esquires and Yeomen vied with each other in their efforts to meet the national want; and the great care and attention resulting from all this enthusiasm culminated in a success so remarkable as to outstrip all former efforts, and as we read the accounts, to make us lament the more, the neglect of later years.

Cider and Perry were then made in large quantities of a more uniform superior quality; and met with a ready and highly remunerative sale. They formed the household family drink, varied on festive occasions with home-made wines, in the excellence of which all good housewives prided themselves. The farm labourers, or hinds, who were at that time usually boarded in the house, had to be content with “Ciderkin,” or “Purr,” a weaker cider, made by the addition of water to the apple cake, as it was passed again through the mill. This was allowed to the men in almost unlimited quantities during haytime and harvest, and formed a wholesome and harmless drink” (Hogg and Bull 1886).

While the quote from Beale above had already mentioned something about making a cider taste more like a wine from the Canary Islands back in 1670, it seems that this kind of practice was still going on around the time of Hogg, as in an 1895 book on the processing of fruit, German author Heinrich Semler describes how the English had been wont to create “imitation wines” based on cider.

“Cider is often used as a “raw material” for making wine, which is especially true of England, where one is often served “real” Burgundy, sherry or port made from cider with other suitable substances. If these drinks were only sold under their true name, there would be no objection to their existence, for they consist of harmless ingredients, whereas this cannot always be said of the genuine wines mentioned. They are all too often adulterated with substances that are dangerous to health. Since these imitations, if well prepared, taste excellently and are only slightly inferior to the genuine articles, the German fruit growers should at least produce their own wines for their domestic use. The considerable sums which now flow out to France, Spain and Portugal for Burgundy, Sherry and Port could then be reduced a little” (Semler 1895).

He goes on to give detailed recipes for recreating Burgundy, Malaga, Port, Sherry, Claret, Bordeaux, Madeira, Muscat de Frontignan, Muscat de Lunel and Alicante wines, all based on cider with various additions. Often sugar, usually some additional fruits, herbs or blossoms, and sometimes fortifying with alcohol.

When I saw these kinds of references it made me wonder if this practice was the original reason for the British made wine tax? “Making wine”, he said. Was making, or rather faking it, essentially punishable by tax? Was it something to protect the wine merchants’ business, or ostensibly to protect consumers? I’m still very curious about it. But as Semler said, if the ingredients are good and natural, why not? But it goes to show that cider was considered close enough to wine in its own right to be used as a base on which to build imitations of other grape-based wines.

The poor relation?

In 1830, Michael Donovan wrote about cider and perry in his book on Domestic Economy, puzzled about the fact that they were not treated as equals to grape wine, when other fruits, similarly made, were generally classed as wines.

“These favourite beverages are, through some singular fastidiousness of arrangement, generally separated from the class of liquors called wines. The fermented liquors made from the juice of currants, gooseberries, and various other fruits, to which sugar is added; and from the juice of grapes to which sugar is not added, or at least seldom, are all named wines. Why the fermented juices of apples and pears should not be admitted to the same class is not obvious: in their nature they seem to be effervescing wines, just as much as champagne, although not so strong, and more sour and sweet” (Donovan, 1830).

Is cider somehow the poor relation of wine? No, of course it’s not. Cider and perry are plenty rich enough in heritage and flavour to stand on their own, but the perception of it has waxed and waned over the centuries.

Just like wine, in the past and especially today, the cider spectrum covers everything from the cheapest, rough industrial muck, through decent, good quality and affordable drinks, perhaps rising to small-batch, artisanal cider made with love and care and an approach that deserves a higher prices tag, right up to the white whales, rare, overpriced and sought by collectors for bragging rights. In wine-producing countries, wine is an everyday drink, and indeed, living close to some German wine regions, I know enough people who prefer to drink wine rather than beer when in a pub or restaurant.

It has ever been the way with any commodity, be it chocolate, cars, phones or houses. Beer, cider and wine are no different, and we can’t expect it to be any different in a capitalistic society. And while in the past few decades (or maybe century) we can probably say that the reputation and market share of cider probably waned quite a lot, and for many reasons, it did swing up again in Britain and Ireland at least, though in a different format, with a firm place in the pub being served on tap. But maybe it is due a correction, a parallel restoration so that a product of the land can be again held in high esteem?

Pintification

The seemingly opposite, but by no means mutually exclusive alternative to the so-called winification of cider is often a desire to see cider in pints. Which is of course fine, as cider is not an either-or situation. I grew up thinking of cider as being something you got in flagons or pints in a pub. I have fond memories of working on the Arann Islands in the early 90s, cycling back from the excavation at Dún Aonghasa and stopping at the ideally placed pub half way to our house for pint bottles of ice cold cider.

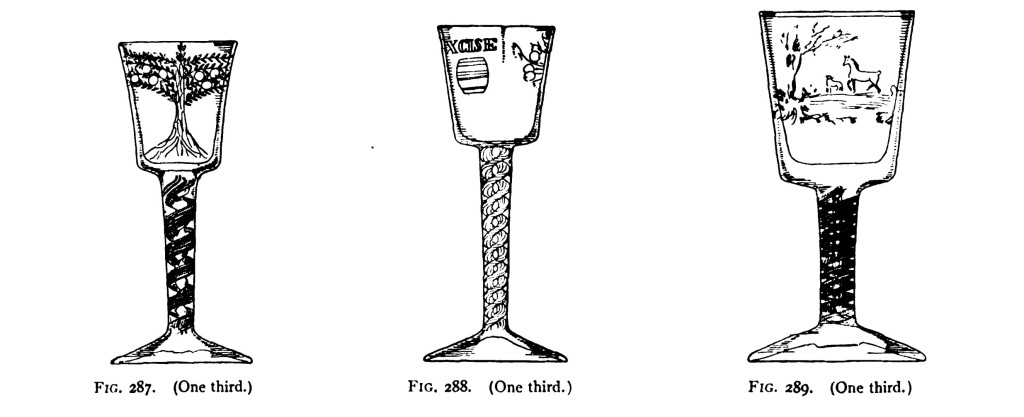

I wondered if it was Magner’s that had “pintified” cider, but it appears not. But it does seem that until the last century, cider was consumed in smaller volumes, with a half pint being the larger standard for a single serving. The Museum of Cider in Hereford have wonderful examples of beakers made of horn for regular drinking in England, and of course those beautiful, very fine blown glass stemware made specifically for serving cider. Those large, three-handled mugs were usually commemorative vessels, made for sharing.

But did the pintification then coincide with the introduction of more industrially-produced products, diluted down and sweetened, so that the lower alcohol was more suited to bigger servings to slurp down? It seems likely, and with it perhaps that link to full juice, full strength dry cider waned even more, as a new tradition was invented on the isles of Great Britain and Ireland

Britain and Ireland do seem unique in that regard. Elsewhere in Europe, the wine bottle and smaller measure is still the standard. In Hesse the standard serving size in a pub is a 200ml beaker, either stoneware or the diamond-patterned “Rippchen” glass. Even in the more agricultural areas, like where I live, the youngsters would be sent down to the cellar to fetch a jug of cider, but it’s drunk from regular-sized glasses or beakers, often cut with a glug of sparkling mineral water, especially after a hot day in the fields.

It makes me think of one of my former neighbours, the elderly Ottmar who made 1,000 litres for himself every year and drank it mixed with water every day after working in the garden. The way it should be drunk, according to an old man who was doing it for decades. And who could deny it?

On an aside, the idea of cider being a watered down, fizzy drink served from tap as an alternative to beer has really influenced what other countries believe cider to be. The website of the Verband der Deutschen Fruchtwein- und Fruchtschaumwein-Industrie e.V. (VdFw) a central association of producers of cider, fruit wine, fruit sparkling wine and fruit wine-based beverages in Germany gives the following definition of cider:

“In the cider mother country, Great Britain, it [cider] is traditionally understood to mean a carbonated cider, often with a distinct residual sweetness, which is usually produced with the addition of water. In Germany, there is as yet no legally defined term for cider. An English cider that comes onto the market in Germany, for example, is declared here as a drink containing apple wine. The VdFw sees the need to standardise understanding and establish minimum requirements and is committed to creating a definition of cider and its production in Germany”

https://www.fruchtwein.org/die-produkte/apfelwein

I find this definition from a formal body frightening, as is completely misses the broad spectrum of British ciders and perries, including full juice ciders, still ciders, and all the other stuff that isn’t made with water and concentrate. I would be dead set against any German definition that differentiated between Apfelwein and Cider, as to me they are one and the same thing in the broad church of cider.

But was there less industrialisation of cider production in this part of Europe, that meant a lower alcohol product more suited for serving from tap like a beer didn’t come about? Perhaps. It seems that in France and in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, cider-making remained very much an agricultural product. In Hessen, around the Frankfurt area, they had pioneered a more factory-like system of mass production in the late 19th Century, but the attitude and approach perhaps didn’t change so much as it was never put on draught and was seldom diluted before being packaged. Indeed, even now it feels like there is a lot of chaptalisation to give the strength of some Apfelweins a boost and consistency across a portfolio. But now you do see canned cider in Germany, 500ml, with CO2, but usually dialled down to the 5-6% range, and sometimes pre-mixed with cola. Yeah, I shivered in horror too. Whatever your preference on serving style or packaging of cider, there are certain things that most might agree are bordering on sacrilegious.

For my own part, I celebrate that there is a wide range of products available and accept that there is an accompanying range of prices, some of which I am also unwilling or unable to pay. Some may be presented more strongly as wine alternatives, but most are simply good, honest ciders and perries, often from artisanal makers, where there is no mass production and no benefits from economies of scale. This may indeed be a factor in how they choose to package and price their products, and who can deny them an honest wage for hard work? Far more important to me, both as a consumer and small maker, is that what is in the bottle, keg or can is as close to full juice as it can be, and as close to its agricultural origins as possible. Whatever the container, it will still always be cider.

*Sack being an old generic term for white fortified wine imported from mainland Spain or the Canary Islands.

Bibliography

Beale, John. 1670. General Advertisements Concerning Cider in Evelyn, John. Sylva, or a Discourse of Forest-Trees, with Annexed Pomona. 2nd ed. London: Royal Society.

Evelyn, John. 1664. Sylva, or a Discourse of Forest-Trees, with Annexed Pomona. 1st ed. London: Royal Society.

Goldast, Melchior. 1576. Rerum alamannicarum scriptores aliquot vetusti. Switzerland.

Donovan, Michael. 1830. Domestic Economy, Volume 1.

Hartshorne, A. (1897). Old English Glasses: An Account of Glass Drinking Vessels in England, from Early Times to the End of the Eighteenth Century. With Introductory Notices, Original Documents, Etc. United Kingdom: E. Arnold.

Hogg, Robert, and Henry Graves Bull. 1886. The Apple and Pear as Vintage Fruits. Hereford: Jakeman & Carver.

Semler, Heinrich. 1895. Die Gesamte Obst Verwertung Nach Den Erfahrungen Durch Die Nordamerikanische Konkurrenz. Wismar: Hinstorff´sche Hofbuchhandlung.

Stafford, Hugh. 1753. A Treatise on Cyder-Making. London.

Worlidge, J. 1678. Vinetum Britannicum: Or a Treatise of Cider. 2nd ed. London.

How dare you demean the wines and ciders of the 500 Worlds of Ultramar!

(Seriously, tho, great article.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had to do a double take as to whether I was on a cider or 40k!

LikeLiked by 2 people

I think a crossover post may be warranted! 😀

LikeLike

Years ago the Common market tried to class cider as agricultural wine to increase the tax It didn’t succeed.surprise surprise !

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Rushed Beery News Notes For A Bloggy Hangover Week – A Good Beer Blog

Pingback: Cider Review’s review of the year: 2023 | Cider Review