In the course of human history, a lot of wine must have been spilled over the pages of books. As both a wine lover and a book lover, this thought is quite upsetting, so I find it a relief to remind myself that even more ink has been spilled on the subject of wine, and not only by professional wine writers. An endless litany of great poets and literary figures, from Euripedes to Hemingway, have explored their fascination with wine through the written word. Academics have penned lengthy tomes about wine and psychology, wine and religion, wine and neuroscience, and wine and philosophy. If there’s one thing that all of these writers agree on, it’s that wine is worth reflecting and writing about: It has played an important role in our culture since time immemorial, and thinking deeply about it can teach us something valuable about ourselves.

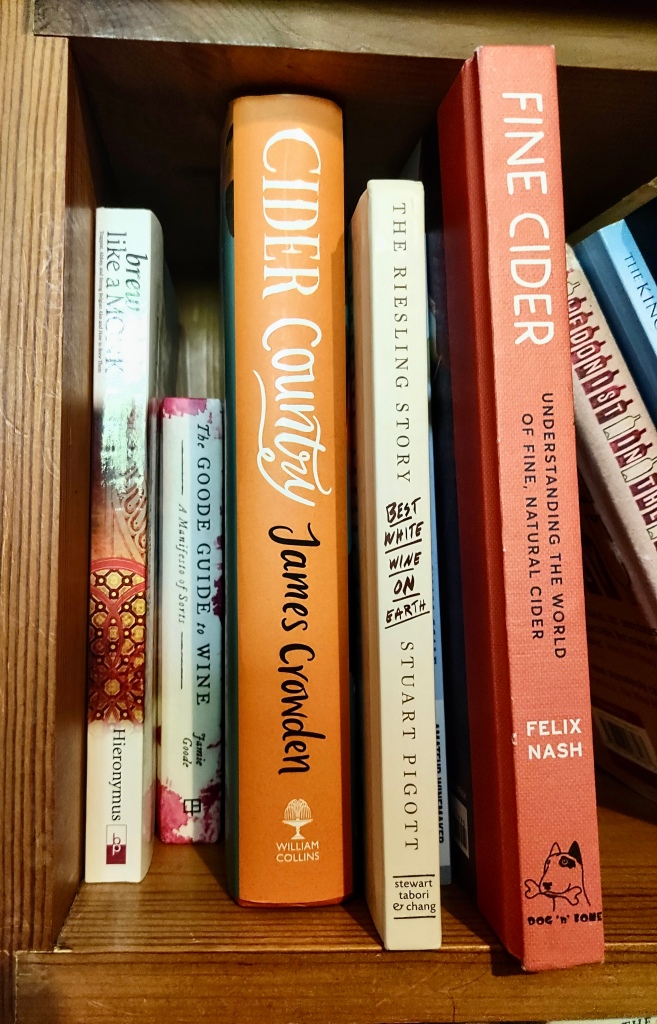

Sadly, cider has received comparatively little attention from writers. There are, of course, the historical Pomonas, numerous pieces by local historians and a handful of excellent books by modern cider writers, as well as our unmissable weekly content here on Cider Review. But the idea that cider is worth thinking deeply about is not especially widespread. There are far fewer professional cider writers than professional wine writers, and cider only makes a very sporadic appearance in the literary and academic worlds. It has all too often been typecast as a symbol of everything that is rustic, rural and unsophisticated; as the poor country cousin to wine’s urbane cosmopolitanism. To this day, writing about cider remains a largely amateur pursuit. There is no better proof of this than the fact that someone like me, with no relevant qualifications other than interest, enthusiasm and a penchant for flowery descriptors, can miraculously get away with having his articles published on a leading cider site.

Today, I’m going to try to demonstrate that cider tasting can be just as complex, challenging and significant an experience as wine tasting. In my view, cider tasting can provide us with similar insight into the human condition, as long as the cider that we are tasting is authentic. I will argue that a cider is authentic when it is clearly rooted in a specific time and place, and I will explore some of the implications of the concept of authenticity for our understanding of cider.

At first glance, my claim that cider tasting can be challenging and complex might seem rather mystifying. For many people, drinking cider is just a way to unwind at the end of a long day or a welcome social lubricant, rather than anything very complicated. From their perspective, tasting cider is the easiest thing in the world. Put some in your mouth, and voila! You taste it. Within a fraction of a second and with zero conscious effort on your part, your neurons transmit signals from the taste receptors in your mouth to the gustatory cortex in your brain. In the space of a few seconds, you can probably decide whether or not you enjoy the taste. If I were unscrupulous enough to give small children some cider to drink, then they would be perfectly able to taste it too. Tasting cider is so easy that it’s effectively child’s play.

But tasting cider is also difficult, at least if you’re a cider reviewer or a serious enthusiast. Reflective tasting, by which I mean tasting with the intention of really understanding what you’re sensing, requires more than just putting cider in your mouth, receiving some sensory signals and deciding whether or not you like them. It demands attention to detail, the ability to identify and distinguish between many different flavours and sensations, and the possession of a suitable vocabulary with which to communicate them. It requires us to put aside our prejudices and preconceptions about what we are tasting, and simply describe the cider exactly as we experience it, yet it also calls for a broad knowledge of the context in which the cider was made. Despite our best attempts to be impartial and objective, our experiences of taste are never only about what’s in the glass. As I discussed in a previous article, flavours and scents have the power to evoke memories and emotions. More importantly, however, artisanal drinks always point beyond themselves, to the complex web of relations that make them what they are.

It is the capacity to express these relations that makes a cider authentic. Authentic ciders are unrepeatable expressions of particular fruit from a particular place at a particular time; an apple variety, an orchard, a vintage. The fruit have a specific set of genetics, the orchard has a specific climate, geology and soil formation, and each vintage has its own weather patterns. To be authentic, a cider must provide us with a snapshot of how these disparate natural properties and forces have come together to make it what it is. It must taste of the apple varieties from which it is made, give us a sense of the place in which these apples were grown, and reflect the weather conditions of the growing season.

Being authentic is not the same thing as tasting good. In fact, a cider can be authentic and nonetheless taste pretty mediocre. There are a number of reasons for this. Firstly, not all apple varieties make equally good cider, and our ancestors hence designated some varieties, such as Dabinett and Kingston Black, as being of superior or ‘vintage’ quality due to their well-balanced proportions of sugar, tannin and acid. I would contend that some culinary and dessert varieties, which were never considered as candidates for ‘vintage’ status, might well deserve to be ranked alongside the best bittersweet and bittersharp varieties, but the fact remains that not all apple varieties are created equal.

Secondly, not all orchards provide equally good growing conditions for apples. How successfully a particular variety of apples grows in a particular orchard depends on a wide range of factors, including the spacing between the trees, the rootstocks to which the varieties are grafted, the amount of sunlight that the trees receive, the direction in which the orchard faces, the steepness of the slope on which it is located, the drainage properties of the soil, the particular microfauna that inhabit that soil and the geological substrate. While numerous wine regions classify their vineyards according to their potential to produce great wine, an official classification of the best orchards for cider production has never been attempted. However, as Adam notes in his recent article on the point of orchards, this doesn’t mean that there are no such privileged sites, and many cider makers acknowledge that some orchards are simply better than others.

Thirdly, not all vintages are equally good for apple growing. In some years, cider producers are blessed with cool, crisp nights and long, sunny days that allow the apples to ripen to perfection. In other years, they are cursed with spring frosts that kill delicate apple blossoms, strong storms that knock apples off the trees and incessant rain that causes them to rot on the branch. Vintage variation is an ineliminable feature of authentic cider production, and not every year can be like the great 2018 in the UK, which produced faultlessly ripe apples with unusually high sugar levels and full, rounded tannins.

If a cider is made from a great apple variety, grown in a perfectly located orchard in a great vintage, then it is likely to taste a lot better than a cider made from a lesser variety, grown in a poorly located orchard in a year with atrocious weather conditions. But these are qualitative distinctions rather than judgements of authenticity, and the better cider is not necessarily any more authentic than the worse one, so long as they are both true expressions of particular apple varieties, grown in particular places at particular times. Authenticity is a matter of being true to one’s origins, not of being good.

Incidentally, viewing cider through the lens of authenticity allows us to reconceptualise what we mean by faults, i.e. the characteristics of cider that are commonly believed to depart from the acceptable norm and detract from our enjoyment. The problem with our ordinary understanding of faults as “things that make cider taste bad” is that different people have differing levels of sensitivity to them, and some people may even like them. Tasting a large number of ciders has taught me that I am highly sensitive to even trace amounts of acetic acid, which invariably tastes unpleasant to me, but that I can sometimes enjoy a bit of Brettanomyces in my cider. However, I can think of several people who love acetic ciders and really can’t stand the slightest hint of Brett. Who’s to say that I have better taste than them, or vice-versa? Ultimately, it seems quite foolish to dictate people’s personal preferences and much more sensible to accept healthy differences of opinion on matters of taste. When it comes to such matters, one person’s fault is another person’s perfection.

Thankfully, the concept of authenticity allows us to explain why a fault is a fault without having to argue about who has the better taste. A characteristic of cider can properly be called a fault not because it makes cider taste objectively bad, but rather because it prevents cider from tasting as authentic as it could be. I am aware that this claim might initially seem surprising. After all, acetic acid is produced by bacteria that naturally occur on fruit and in the cidery. Hydrogen sulphide is a natural byproduct of fermentation, and Brettanomyces is a genus of yeasts that live on the skins of fruit. These compounds are as much a part of the natural environment that constitutes a cider as the apples and trees themselves. Do they not, therefore, inevitably contribute to the authenticity of the cider in question?

On balance, my answer to this question is “no”. When compounds such as acetic acid, Brettanomyces and hydrogen sulphide are excessively present in a cider, they dominate the overall flavour profile and obscure the natural properties that we might otherwise perceive. A cider that is highly acetic tastes like every other highly acetic cider, i.e. intensely vinegary. A cider with elevated levels of hydrogen sulphide always tastes of rotten eggs, and a cider with lots of Brett always tastes like sweaty saddles. In all of these cases, subtle variations between different apple varieties, orchards and vintages tend to be overpowered by the tyrannical presence of a single chemical compound. We can’t fully sense the fruit, the orchard and the vintage, because the fault gets in the way and blocks our perception of these relations. A faulty cider can not, therefore, taste authentic in a holistic sense.

So far, I have only discussed the natural dimension of authenticity in cider, but I believe that it also has a cultural dimension. Although cider production begins in the orchard, it is not a purely natural phenomenon. Ciders don’t make themselves. They are produced by people, who make a wide range of choices and interventions throughout the cider making process. Authentic cider therefore expresses the natural forces and materials used to create it, but also reveals these human choices and interventions, including decisions as to which varieties to plant in which locations, how to prune the trees and maintain the orchard, when to pick the apples, which style of cider to aim for, which varieties to blend with each other, which yeast strains to use, which vessels to ferment the cider in and when to bottle it. These interventions take place in a wider cultural context that is itself worthy of detailed exploration. In my view, ciders are authentic when they are repositories of cultural memory; of knowledge passed down through history and reinterpreted by each successive generation of cider makers.

This cultural dimension of authenticity has just as significant an impact on what we taste as the natural dimension. It is why a keeved cider made in the Norman tradition would always taste entirely different to a dry cider, even if they were to employ the same apple varieties, and why Traditional Method ciders take on flavours that are substantially different to their Pét Nat counterparts. There are a myriad of ways in which cider makers have sought to capture and express the flavours of their fruit to reveal its terroir, many of which are rooted in long-standing cultural tradition. In the craft cider industry, there is considerable disagreement about which of these methods produces the most authentic ciders. Some producers believe that still, dry ciders are the purest expressions of place and time, while others would argue that keeving softens tannins and allows the fruit to take centre stage, or that ice ciders concentrate natural sugars and acids to give them their fullest possible expression. From my perspective as a consumer, all of these points of view have their merits. The stylistic diversity of cider deserves to be celebrated, because different methods highlight different but equally fascinating aspects of the web of relations that constitutes cider as authentic. More broadly speaking, however, the cultural dimension of cider should be respected because it contains all of the core themes of human history. It is replete with tales of migration and displacement, commercial success and ruin, family alliances and conflicts, scientific discovery and hard, unremitting work. It is a rich source of insight into the human condition, and its story demands to be told and studied just as much as the story of wine.

When we taste authentic ciders reflectively, we attempt to unravel the complex network of natural and cultural relations that I have briefly outlined. This unravelling is a gradual process, in which ciders slowly reveal themselves to us. The more that we taste and learn, the more we are able to associate scents, flavours and textures to particular apple varieties, locations, vintages and production processes. In the course of our learning, we develop new insights into the natural and social worlds. We discover the microscopic worlds of yeasts and soil fauna, encounter unfamiliar concepts in biology and chemistry, and learn about cider producers’ evolving ways of life. But ultimately, tasting reflectively teaches us that cider conceals more than it reveals. We only ever catch sight of these worlds through a glass darkly. In fact, achieving a full understanding of the cider that we are tasting is not only very difficult, but literally impossible.

Achieving a complete understanding of even a single bottle of cider would require us to be historians, sociologists, linguists, geologists, meteorologists, orchardists, microbiologists, biochemists, neurologists and psychologists. As far as I’m aware, no-one is an expert in all of those fields, and many of us aren’t experts in any of them. But even the greatest polymath would inevitably fail to understand cider in all of its complexity, because a full comprehension of the cider in your glass would require you to acquire knowledge that no-one currently possesses, and that may be inaccessible or entirely lost. The precise chemical makeup of the cider in your hand has probably never been exhaustively analysed, and the geology of the orchard from which the apples were picked is unlikely to have been extensively surveyed. Our understanding of the relations between taste and memory is still in its infancy, and much of the history of cider making has never been recorded. Our language is not rich enough to accurately describe every flavour and sensation, so we have no choice but to struggle to identify them and search in vain for the right words to express them, before resorting to using metaphors. When it comes to understanding cider, we are all still emerging from our caves into the bright sunshine of the orchard, frantically feeling around in the dark and waiting for our eyes to adjust so that we can take in the beauty of the landscape.

Tasting cider reflectively is therefore a daunting task. We are continually confronted with our own ignorance, and reminded that the world is a big place and that we are small and insignificant. It reveals the limits of our understanding and shines a spotlight on our human finitude. However, this is also why cider is endlessly fascinating. There is always something new to discover; new flavour combinations to encounter, new vintages to explore, new snippets of information to be acquired. My advice to those just beginning their cider journeys is to taste and read as widely as possible. Trust your own palate, but be prepared for your tastes to change with time. Be confident about what you have learned, but be honest with yourself about the limits of that knowledge.

Since our understanding of cider has inevitable limits, there can be no fully authoritative experts on cider. We are all at different stages in our journeys of cider discovery, but no-one, no matter how knowledgeable, can ever reach the final destination and achieve an absolutely exhaustive understanding. Take the example of our esteemed editor, James. He has tasted many more ciders than I have. If he continues to taste them at his current rate, I’m unlikely to ever catch up with him. He is also a cider maker and undoubtedly understands the process of cider production in much greater depth than I do. There are many things that I can learn from him about cider, but this doesn’t mean that he knows everything, or that his opinion is invariably correct. I may even occasionally be able to teach him something, if only by asking him an interesting question that he hasn’t thought about before. Understanding that no-one has all of the answers is liberating, because it frees us from our submission to the authority of supposed experts, but it also reminds us of the importance of epistemic humility. Remember, the fact that no-one knows it all means that you don’t either!

While it’s impossible to ever fully grasp authentic cider in all of its complexity, it is quite easy to understand that not all ciders are authentic. I have alluded to this in my discussion of faulty ciders, but there is another, much more important category of ciders that fails the authenticity test. Mass-produced ciders, made in industrial facilities from apple concentrate, water, sugar and additives, deserve more scorn than even extremely faulty ciders, but not for the reasons that we usually appeal to. If you put two cider makers or reviewers in a room and ask them to debate the respective merits of keeved ciders and dry ciders, or wild yeasts and cultured yeasts, they will probably still be arguing long after you’ve gone to bed. However, if there’s one thing that almost everyone in the craft cider scene can agree on, it’s that industrially-produced ciders are a stain on cider’s reputation. There’s no better way to make enemies and alienate people than turning up to a cider tasting clutching a six pack of Strongbow.

If you ask cider enthusiasts why they dislike mass-market ciders, they are likely to reply that they are foul-tasting concoctions that can’t hold a candle to proper, artisanal ciders. To be honest, I’ve been known to express opinions of this sort, but I recognise them as an expression of tribalism; a performance that marks me out as a member of the craft cider scene, rather than a statement of objective fact. When I manage to think about ciders like Kopparberg and Magners dispassionately, it becomes very clear to me that they have been carefully designed to please the largest number of people possible. With their uncomplicated fruity flavours, intense sweetness and high levels of carbonation, they appeal to exactly the same tastes as alcopops and carbonated soft drinks, which are enjoyed by millions of people around the world. They also achieve an extremely high level of consistency and are hardly ever objectively faulty. Magners may be exceedingly sugary and entirely one-dimensional, but I challenge you to find a bottle that has any perceptible trace of acetic acid or hydrogen sulphide.

The claim that these kinds of ciders are actively unpleasant therefore doesn’t really stand up to scrutiny. It relies on the assumption that we cider enthusiasts are more sophisticated in our tastes than those people who like simple, sweet, fruity flavours. The problem with that assumption is that we have all been those people. Who among us can honestly say that we have never enjoyed fizzy drinks, sweets or mass-produced desserts? I bet that a lot of us still do, if only as an occasional treat. Let he who has never had a can of Coke cast the first stone, as the saying goes.

One advantage of viewing cider in terms of authenticity is that we can criticise industrial ciders without becoming snobbish about our superior sense of taste. The problem with mass-produced ciders isn’t that they taste objectively bad, but rather that they are inauthentic, in the most egregious way possible. Their existence is completely disconnected from the network of relations that constitutes cider as a multifaceted marriage between nature and culture. They are made in factories from processed ingredients following a fixed recipe, and therefore have no clear sense of place and only the most tenuous connection to the fruit from which they are supposedly produced. They don’t reveal the passage of time, but are produced through a monotonous repetition of the same industrial processes. They don’t tell a story about whimsically-named apple varieties, the vagaries of the seasons and time-honoured ways of life, but mutely trigger pleasure receptors with mechanical predictability. Like painting by numbers, they reduce an almost infinitely complex spectrum of colour to a few primary smudges. If a glass of authentic cider is a window onto life in all of its messy, exuberant glory, then a glass of industrial cider is a computer screen through which we see a robotic imitation of life, ruled by algorithms and anonymous accountants. It’s a cold, dead and soulless place; the NFT to authentic cider’s fine landscape painting.

One troubling feature of modern life is that we spend an ever-increasing proportion of our work and leisure time sitting behind screens, in a virtual world that threatens to disconnect us from the natural world and uproot us from the bonds of genuine community. Even the food that we eat is often completely detached from nature and offers precious little in the way of sensory stimulation: It comes wrapped in plastic and is carefully divested of any trace of the soil in which it was grown, before being chilled to a temperature at which it loses most of its sensory properties. We are drawn to artisanal cider because we crave a connection to enduring cultural practices and a closeness to the natural world. We want to feel something real and authentic, as an antidote to a way of life that can feel alienated, meaningless and essentially quite lifeless. The choice between authentic cider and industrial cider therefore isn’t a question of taste; it’s a matter of life and death. We must choose between cider as a unique expression of a way of life in which human purposes are intricately interwoven with nature’s gift, and cider as merely an exchangeable commodity, with no more meaning than any other mass-produced object.

Let me conclude my long-winded essay with a simple plea: Choose life. Choose authentic ciders made from real apples by real people, not liquid commodities made in factories owned by faceless corporations. Visit an orchard, meet a cider maker and taste how nature and culture have come together to produce this unique, fascinating drink. Choose the unpredictability of the seasons and the possibility of human error, not the mind-numbing consistency of a world ruled by machines. Choose engaged, reflective tasting over careless consumption. Face the daunting reality of human finitude and embrace the infinite opportunities for discovery, instead of capitulating to the cold, repetitive comforts of the virtual world. Choose wisely, because so much depends on your choice.

A lengthy but very complete analysis and reflection on all ciders and the varied nature of them.

Suitably dismissive of the watered down and flavoured mass produced options!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your kind comments, Oliver. I’m really pleased that you enjoyed reading my article. I appreciate the support of anyone who cares about authentic cider, but it always means that much more when it comes from a cider producer.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I refer back to this again and again. Such a great analysis of what cider has to offer. And an eye-opener for consumers, who have unwittingly curtailed their enjoyment of cider.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much for your positive feedback. I really enjoyed writing this article and it’s probably my favourite piece that I’ve had published on Cider Review, so it’s great to hear that you are enjoying and referring to it.

LikeLike

Extremely well written article, enjoyed it a lot. I am convinced, that the genuine taste of a fermented apple can only be reached by fermenting spontaneously, with wild yeast. Therefor an authentic cider should be made without (or with as minimal as possible) intervention.

LikeLike

Extremely well written article, enjoyed it a lot. I am convinced, that the genuine taste of a fermented apple can only be reached by fermenting spontaneously, with wild yeast. Therefor an authentic cider should be made without (or with as minimal as possible) intervention.

LikeLike