Cider terroir is a wild frontier compared to wine’s well-trodden terra firma. It is a hot topic, yet I often find myself at the bottom of a rabbit hole, shovel in hand, when I seek the detail. My aim here is to provide a sketch map of this terra incognita as it stands.

As Adam has so succinctly put it, terroir is little more than farming at its heart. Some crops naturally grow better in certain places and good cider is founded on excellent fruit. In its most objective sense, then, cider (and perry) terroir constitutes the diverse interactions between physical environment and orchard ecology that shape fruit growth and character.

Crucially though, terroir also spans the ways orchards are managed within their natural setting and how this shapes cider production from them. It is as much an imposition of agriculture as a cooperation with nature, whether by traditional savoire faire or pioneering effort. Any location will create its own version of this balance, wrapping terroir’s agricultural heart in a unique geographic identity that evokes authenticity, quality and value in its products.

Practically, this is why we hold terroir in such regard for cider, and not least because of its commonalities with wine. Yet it is often little more than a passing comment in news articles or producer interviews. In Bill Bradshaw and Pete Brown’s 2013 World’s Best Ciders: Taste, Tradition and Terroir, the ostensible latter third of the book occupies barely a paragraph. Cider Review articles have waded deeper into aspects of cider terroir, kicking off with Adam’s 2018 visit to Burrow Hill, but a wider look at the topic is sorely needed.

Paradoxically, a full tour of producers, soils and climates is prohibited as much by a lack of data as by how long such an article would nonetheless become. What I instead want to focus on is where cider terroir has come from, what little we know with any clarity, and where it may yet go. It’s a long haul (charge your glass accordingly), but I hope a worthwhile one.

Words from the past

Cistercian monks in 11th century Burgundy are celebrated as the discoverers of terroir1,2 – a culturally French concept requires French heroes, non? Really, their meticulous records of vineyard conditions and wine quality are just the oldest that have survived into the present. By other names, terroir is undoubtedly older. Adam points to a remark by Palladius in his Opus Agriculturae, that ‘a stony pear will change its flavour if it is grafted into generous land’, showing the concept was alive and kicking in the pomme fruit world seven centuries before the Cistercians founded their monasteries.

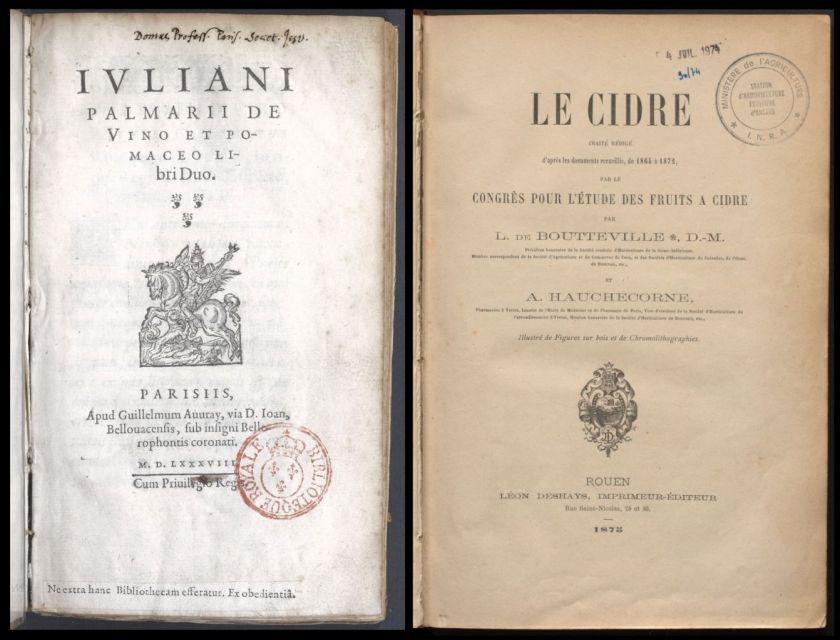

Latin also remained the monastic language of scholarship. Terroir as a term had instead mutated from Latin (territorium) via Old French (tieroir), both meaning land or territory, and came to refer to any land used for crop cultivation in Middle French by the 13th century3. An inconspicuous origin, then, and certainly not as some highfalutin’ marker of quality or identity. It was only during the Renaissance that terroir saw use in context more familiar to us, but remarkably cider was present at this turning point. Julien Le Paulmier, in translating his Treatise on Wine and Cider from Latin to French, commented:

‘The terroir contributes as much to the strength and virtue of ciders as to wines …. The Cotentin is the best for excellent ones. The Pays-d’Auge makes them powerful and virtuous, but for the most part thick, coarse and poorly clarified. The Pays-de-Caux gives them a taste of the terroir, at least in some places where there is marl.’ [Le Paulmier, 1589, Treatise on Wine and Cider].

Ciders were as highly valued as wines by the nobility and an agricultural guide published by the Marquis de Chambray shows that regard for terroir continued well after Le Paulmier, even if Cistercian rigor was lacking:

‘We cannot say precisely what kind of soil will give the best cider; experience alone can teach in this respect: the richest bottoms of Normandy, the Cotentin where Isigny is, the Pays d’Auge, give excellent ciders.’ [Louis de Chambray, 1754, The Art of Cultivating Apple Trees, Pear Trees and Making Ciders According to the Usage of Normandy].

English pomologists also latched onto the concept of terroir as Europe tipped into its scientific Enlightenment. Serendipitously, many founding members of England’s foremost learned organisation, the Royal Society, were also cider nerds. Successive editions of John Evelyn’s Pomona, one of its first scientific publications, make clear reference to how geographic setting shaped cider and perry quality:

‘He that would treat exactly of cider and perry, must lay his foundation so deep as to begin with the soil… neither will the cider of Bromyard and Ledbury equal that of Ham Lacy, and Kings-Capell, in the same small county of Hereford.’ [John Beale, 1664, Aphorisms concerning Cider. In Pomona, 1st edition].

‘About Taynton, Five Miles beyond Glocester, is a mixt sort of land, partly Clay, a Marle, and Crash, as they call it there, on all which sorts of land, there is much Fruit growing, both for the Table and for Cider: But it is Pears it most abounds in, of which the best sort, is that they name the Squosh-Pear, which makes the best Perry in those Parts.’ [Daniel Colwall, 1679, An Account of Perry and Cider out of Glocestershire. In Pomona, 3rd edition].

Perry also shows, however, that regionality was not always founded on terroir. In the second addition of Pomona, John Evelyn pronounced Switzerland’s Turgovian pear as responsible for the ‘most superlative perry the world certainly produces.’ English cider makers were certainly not blind to regional reputation beyond their borders as well as within, but the emphasis here was on variety rather than growing location.

Terroir as a term also took a sharp diversion through the 17th and 18th centuries. This is why, despite their veneer of modernity, a gulf of time and meaning separate early references to regionality in cider from the modern cider terroir conversation. To taste terroir – linguistically still a reference to land – was to experience a crude character shaped by natural setting. Even for Le Paulmier, it was often something inelegant or dirty; gôut de terroir, lauded by vintners today,was essentially a mouthful of soil. Provincial vineyards, at the mercy of their rural, unsophisticated settings, could only ever offer ‘terroir wines’ fit for the peasantry, themselves made rude and rough by that same land. By contrast, the carefully cultivated vineyards of the Île-de-France (the area around Paris) were free from terroir, producing elegant ‘cru wines’ reserved for the nobility.1,2

In England, cider underwent an analogous division. Hugh Stafford in his 1753 Treatise on Cyder-making distinguished ‘fine cider’ from ‘rough cider’, but along methodological rather than regional lines. Concurrently, French wine imports to England were hamstrung by parliamentary embargoes and taxation, with the nobility turning to fine cider as a high-quality alternative. Cider had been compared to wine across the centuries but terroir, an untranslatable term steeped in a largely inaccessible market and bearing connotations of crudity, lacked any cultural weight across the English Channel.

Away from England and France, early references to cider terroir appear more muted. In Asturias, Antonio Cauredo Cuenllas, writing in 1785 to a fellow priest in Leon, commented on ‘the delicacy of the fruit of Villaviciosa the reason of being superior to other coming from Biscay or England’, but it is not clear if this opinion reflected terroir or varieties. The apparent lack of references to terroir for sidra and sagardoa could be artefacts of my own language barriers and what information was available online. Barry, however, corroborates a similarly striking void in the literature regarding regionality in apfelwein and viez despite their deep traditions.

Absence of evidence does not evidence absence. Still, geographic variability in discussion of the concept of terroir suggests that it may have only reared its head when regional reputation catapulted cider into the ranks of high society. Asturian, Basque and Hessian cider cultures catered to largely static agrarian consumer bases as affordable alternatives to wine and did not garner the stellar reputations afforded to cider and cidre in England and France.

Early American cider culture adds to this impression. The founding fathers were fond of fermented apples, wealthy landowners maintained a predilection for the pioneers’ drink, and lively domestic and international trade in apples and cider again drove interest in the conditions which produced the best of both:

‘The middle States possess a climate eminently favourable to the production of the finer liquor [cider] and table apples: it will probably be found, that the Mohawk river in New-York, and the James river in Virginia, are the limits of that district of country which produces apples of the due degree of richness and flavour for both purposes.’ [William Coxe, 1817, A View of the Cultivation of Fruit Trees, and the Management of Orchards and Cider].

Perhaps, then, there has always been an economic facet to terroir. Certainly, it seems this way for wine. The Egyptians developed notation to distinguish vintages from vineyards of different quality, while the Greeks stamped wine amphorae with seals of origin to denote regional excellence, many thousands of years before the Cistercians set their vines. Some footnote from the wealthy monasteries of Navarre or the estates of Charlemagne may yet stretch cider terroir further back in time. By contrast, nobody in the past spoke of the terroir of turnips.

Pestilence, war and wine

Terroir recovered its reputation amongst French vintners by the end of the 18th century. Its meaning had shifted once again from denoting a lack of sophistication to a more equitable recognition that growing conditions anywhere could make or break a vintage.1 In turn, the international acclaim of French wines could only mean that French terroir was something to be celebrated. Vive La France!

Calamity then struck in the middle of the 19th century. Vineyards across Europe were hit by phylloxera, an insect pest inadvertently imported on American rootstocks. Many French winemakers turned to unscrupulous practises to maintain production, and the international reputation of French wines plummeted.

Capitalising on the sudden gap in the drinks market, Normandy cider makers set about systematically improving cider production, echoing how diminished wine imports to England centuries earlier led to cider’s star rising amongst the English aristocracy. Their work culminated in landmark synthesis, Le Cidre, and another remarkable advance – the first scientific evaluation of cider terroir. Replete with lists of apple varieties and quantitative data published on apple juice and cider chemistry, it comments:

‘Tradition here is in complete agreement with scientific observations, and there is indeed a genuine taste of terroir specific to certain ciders.’ [Le Cidre, 1875].

English pomologists, concerned by declining numbers of traditional orchards, were inspired by the efforts taking place in Normandy.The Apple and Pear as Vintage Fruits, published by Robert Hogg and Henry Bulla decade after Le Cidre, also draws attention to the role of terroir in shaping cider, highlighting the presence of Old Red Sandstone soils in two of England’s cider-making heartlands, Devon and Herefordshire. The importance of varieties was not lost though:

‘Herefordshire is not so much indebted for celebrity as a cider county to her soil, as to her valuable varieties of fruit.’ [The Apple and Pear as Vintage Fruits, 1886].

The Americans’ love for apples had not waned through wars both international and domestic, and terroir reared its head in an extensive publication comparing ciders from the USA and Europe, again with a noticeably scientific focus:

‘Soil and climate certainly play a very important role in the production of all fine wines. Do they play an equally important role in the production of ciders? The chemical data on varieties grown in different countries must in part answer this question.’ [William Alwood, 1903, A Study of Cider Making].

British makers, astonished by the sheer quality of American New Town Pippin ciders, cast aspersions that their competitors were artificially enhancing their products. George Embrey tackled the issue in a research article published in The Analyst in 1891, comparing chemical compositions between English, Breton and American ciders4. A decade later, Embrey’s peer, Alfred Allen, published in the same journal on cider and perry’s regional variation5, presciently commenting:

‘The geographical origin allows of some differentiation in the character of cider, but the terms ‘Devonshire,’ ‘Herefordshire,’ ‘American,’ etc., have not the same definite meaning that attach to the names Burgundy, Bordeaux, Champagne, Port, etc., in the case of wine.’ [Allen, 1902. The Analyst, 27: 183–192].

Regional reputations that recognised the roles of terroir and varieties alike were alive and kicking amongst cider cultures in the 19th century, even with the onset of industrial production. Rapidly emerging scientific disciplines – geology, meteorology, ecology, microbiology, analytical chemistry and statistics – gave its makers the framework to tackle cider’s variation with newfound precision. So, why did it all go sideways? Why is the modern terroir conversation seemly so far removed from these promising historic precedents? The answer lies with cider and wine’s divergent fates through the 20th century.

Following phylloxera’s devastating effects, regional French wines needed resuscitation. Increasingly stringent legal defibrillations culminated with the creation of the first Appellation d’Origine Contrôlée (AOC) delineations in 1935. AOC status ensured that anything sold as a regional wine was the genuine article, coming from a geographically discrete area marked by a unique terroir. Building on its revival at the end of the 18th century, terroir now formed the beating heart of fine French wine.6

Cider, however, kept taking turns for the worse. Already facing competition from beer-hungry German and Irish immigrants, cider production in America was decimated by another insect pest, San Jose Scale, in the 1890s until its death knell under prohibition in 1919. Production in Germany and France withered as orchard workers and apple-derived alcohol alike were consumed by the World Wars. Asturian and Basque cultures, including their ciders, were crushed under General Franco’s dictatorship. In Britain, sale of fruit to industrial producers became more profitable than craft production through the early 20th century. Fireblight then struck in the 1950s, prefacing the mass replacement of the variety-diverse, traditional low-density orchards by high density plantations of dessert varieties, or a few cider varieties selected to support industry. Reintroduction of cider tax in 1976 struck yet another blow to the sustainability of small-scale artisanal production.

Wine did not suffer the World Wars unscathed. In the wake of WWII, production in AOC regions once again faced a crisis of reputation and diminishing value compared to the proliferation of cheap table wines. Worse still, upstart New World makers were encroaching on the global market. The response of the French old guard was to defiantly fall back to their tradition of terroir, elevating it from the basis of regionality to something almost mystical.6 New World wines or cheap table vintages could never hope to compete in quality as they lacked terroir altogether, in contrast to France’s time-hallowed regional vineyards. It did not take long for AOC wines to recover their global reputation and market value. Today, an entry-level bottle of Domaine Romani Conti will set you back thousands of pounds.

Terroir ultimately acted as a saviour to French wines as an inimitable marker of quality. Lacking its own idiosyncratic, yet effective formulation of regionality to protect its prospects, pestilence, war, and shifting markets collectively drove cider’s wider fall from grace. This raises a final question, though. Why did cider terroir not develop in the same way in France where the term had originated? In fact, it partly did.

Following concerns over the repurposing of alcohol and copper from stills for the German war effort, Calvados Pays d’Auge AOC was established in 1942. The first ever non-wine AOC was partly defined on varieties and production techniques, but Calvados makers also hired a geographer, Marcelle Reinhard, to delimit its geographic borders according to physical terroir.7 This pioneering effort did not spread further, however. French ciders simply did not bear the same international acclaim as their wines. Lacking strong economic value or the safety net of legally enforced quality control, regionality and reputation fell by the wayside and cider terroir went quiet.

The modern conversation

Following cider’s slide towards industrial homogeneity in the 20th century, French wine ultimately created a lifeline for its regional identities. AOCs inspired the EU’s system of protected geographic indications and designated origins (PGIs and PDOs). Established in 1992 to protect the unique relationships between product and place, this opened the concept of terroir enshrined in its antecedent AOCs to a wider range of goods.

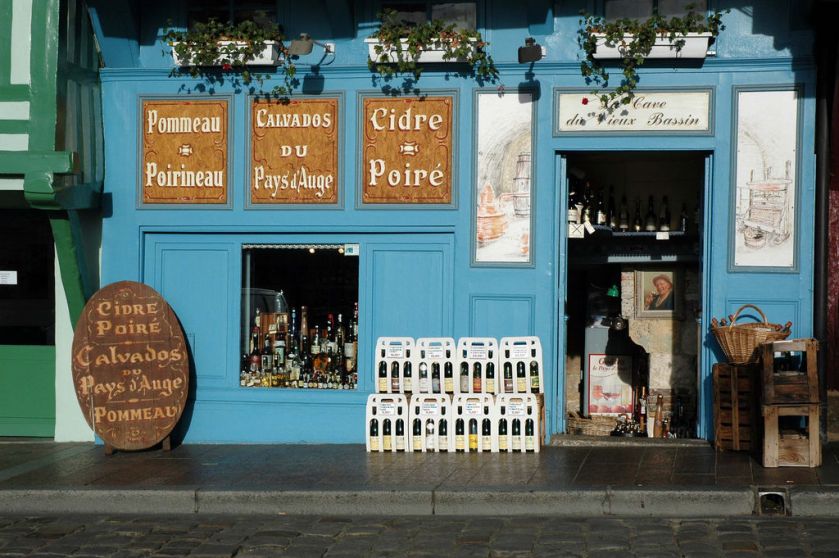

Cider makers were quick to take notice, although terroir was not front and centre in the conversation. Rumours within the Three Counties Cider and Perry Association, founded just a year after the EU’s GI system, were that French makers sought to enter the growing UK market with UK-style ciders of their own.8 The first UK PGIs were established shortly after in 1996. Really, French makers were more concerned with their fate of their own orchards and production traditions. Cidre Pays d’Auge and Cidre Cornouaille secured PDO recognition in 1996, followed by Poiré Domfront in 2002.

Even though cider GIs are predominantly cultural entities, they revitalised the anchoring of regional identity in the landscapes where cider was being produced. By rebooting historic discussions in a context informed by wine, they form the basis for the modern terroir conversation. GIs from Normandy and Brittany (most recently Cidre Cotentin PDO and Cidre du Perche PDO) stand out in their level of detail, explicitly with the term terroir in their documentation, but the Hessian Apfelwein PGI, Norway’s Sider fråHardanger PDO, Sidra de Asturias PDO, Basque Euskal Sagardoa PDO, and Sidra da Madeira PGI all pay some regard to how regional geology, soil, climate or topography shapes varieties and production.

Around the same time as the first cider GIs were established, terroir truly slipped into the Anglosphere, with its written usage surging by 1250% through the Noughties6 as long simmering arguments over terroir versus technique in winemaking rose to a head.One of the oldest contemporary references to cider terroir I could find comes from an interview9 published in Saveur around the same time (what remarks might lurk in still older, print-only French lifestyle magazines, I wonder?):

‘[Eric] Bordelet maintains, however, that terroir, not technique, is what truly distinguishes his ciders from others. Argelette, he notes, is named after the metamorphosed schist that is characteristic of the soil in his orchards; it makes northern Mayenne’s ciders darker and more structured than the suppler, sweeter ciders of the Pays d’Auge, he says.’ [Jacqueline French, 2002, When Fine French ‘Wine’ is Cider].

The terroir conversation has since exploded with the rise of the fine cider movement. Its digital footprint, spanning producer blurbs, bottle pictures and web articles, paints a vibrant picture of its scale as old comparisons with wine have found new relevance. Individual makers and regional cider communities alike are all talking about terroir.

In France, the homeland of terroir, Julien Frémont, Jérôme Forget and Eric Bordelet were firm proponents of cider terroir even before the conversation truly bloomed. Its GIs now provide a ready blueprint for its makers to talk about terroir, while efforts to outline new cider terroirs are emerging in the Loire and the Pays d’Othe, taking cues from their well-established wine cultures.

Across the English Channel, I have had plenty of opportunities to speak to makers around the UK and interest in terroir spans from Cornwall to the Cromarty Firth. Pomologists in Herefordshire, Monmouthshire and Devon have long noted the conspicuous relationship with their red sandstone soils. Julian Temperley of the Somerset Cider Brandy Company was another early champion of cider terroir. Little Pomona’s Taste of Terroir or Wilding Cider’s single orchard vintages are superb examples of terroir-driven focuses at the scale of a single producer.

From my trawl of producer interviews and websites, I sense that identity in other traditional European regions is perhaps rooted more in varieties and tradition. Nonetheless Spain’s Exner, Valveran and Zapiain all proudly mention terroir (or terruño) on their websites and interest is present as far afield as the Canary Islands, where volcanic soils are a hot topic for cider as for wine. In Germany, the Trier Viez Brotherhood recognises similarities in their regional climate and meadow orchards to that of Hessian apfelwein. Mostviertal perry in Austria stalled in its journey towards PGI recognition8, but makers in the region speak of their moisture-retaining clay soil and high altitude with trees growing above the fog line, as producing exceptional fruit for fermentation. Rumblings of terroir abound in contrast to historic quietude.

Away from the traditional European cider regions, Baltic producers have undertaken intensive research over the last few years into their soil types, varieties, and the characteristics of fresh juices and finished ciders. They are on the cusp of releasing the first map of their regional cider terroirs. The Norwegian Institute of Food, Fisheries and Aquaculture Research investigated Hardanger varieties and terroir from 2020 to 2023 to understand how best to communicate the styles and flavours of its ciders to a rapidly growing market. At the northernmost outpost of the cider world, Sweden’s Brännland, alongside Bute Cider and Finland’s Liselunds Cider, seek PDO status for Bothnian ice cider, stretching cider terroir’s codified extent to new latitudes. Reliant on the natural cold across the Gulf of Bothnia, all exemplify how terroir can encompass human practice as well as apple growth.

On the opposite side of the Atlantic, American cider makers talk of how their growing conditions shape their identities from California to New England. Craig Cavallo and Dan Pucci’s 2021 book American Cider details the soils and climate in production areas across the country. Darlene Hayes, cider educator and author, draws on her background as a biochemist to rigorously quantify the effects of terroir in cider. Cider equivalents of American Viticultural Areas (AVAs are the States’ answer to AOCs) have yet to be established, nonetheless, formulations of terroir approaching the detail displayed by French GIs are prominent in wine regions like Hudson River Valley, Finger Lakes or Lake Champlain in New York State, where communities of makers draw directly on the well-established influence of the AVA to understand how that same setting shapes the unique quality of their ciders.10 If anyone shows how American terroir is done, it is surely Eve’s Cidery. Over the border, cider-making communities in Canada are no different. Similkameen Valley in British Columbia. Prince Edward County in Ontario. Nova Scotia’s Annapolis Valley. Montérégie or the Eastern Townships in Quebec. Without the frigid climate of its terroir, the style and the PGI of Quebecois ice cider would not exist.

In some cases, notions of terroir fall in line with established trends. For makers like Wilding or Antoine Marois, their ciders reflect the micro-variations across their orchards. Producers in Pays d’Auge take pride in the wider terroir of their PDO, bocage rooted in clay and limestone, just as any vintner in Champagne celebrates their chalk soils. Whenever the aphorism that the best English perries are made in sight of May Hill crops up, I recall the division between premiere cru and grand cru, which take Burgundy and Alsace’s terroir-bound wine AOCs and salami-slices them to ever finer degrees of geographic prestige.

Other makers appear to turn terroir on its head. Burgundy’s Eclectik harvests apples from across France, treating them a ‘palette of terroirs’ from which they paint their cuvées. To a militant terroiriste, this throws the specificity of maker and landscape out the window. I am reminded instead of Pangaea, created by Michel Rolland in 2015 from classic Bordeaux varieties harvested from the world’s most prestigious wine regions, old and new, to produce a ‘wine of the world’ with a global terroir.

For the rest of the globe where cider cultures are new or modern revivals of near extinct traditions, stirrings of terroir are widespread: Ireland, Portugal, Switzerland, Sweden, Lebanon, Australia, Mexico, Chile, New Zealand and more. Here, codifications of terroir are perhaps less detailed compared to historic or GI-protected production areas, pointing to ideal climates or generous soils.

This variation in detail is not unexpected. At the end of the day, there is only so much space on a bottle label and most consumers will not care about slope aspect or bedrock composition (much to my geological chagrin). Even in well-established cider regions, specific details from individual makers are not always forthcoming. I do not think for a second, however, that this undermines the value makers continue to place in terroir. In every reference, there is a deep-seated sense of pride in natural setting that is free from the past vainglory of French AOC wines. It is instead aspirational, a mass cry around the globe of ‘we are here and this is who we are!’

This is part of what makes cider terroir so exciting, that it can mean so many things to different people and keeping cider’s lexicon flexible and accessible can only be a good thing.11 I also sense, however, that there is a much greater wellspring of terroir knowledge bubbling beneath the surface of the cider conversation than is currently documented. Cider makers are inquisitive by nature and necessity, intuitively coming to understand their climate and soil as they strive to get the best out of a harvest which changes year on year. Web articles and podcasts hint at a wealth of conversations unrecorded at cider conferences and competitions alike. Tantalising references are made to producers pouring over geological and topographic maps to establish what makes their orchards tick. All I can do is to urge any cider makers reading this is to please write about your terroir online! Only with documentation can the sketch map of cider terroir evolve into a fully-fledged cartogram.

What science has to say

This is a major issue, then, that the conversation currently faces. Cider terroir often leans on wine’s pedological and climatic cues. Wine, however, has received decades of intensive scientific research to understand how its terroir works and the debate remains lively.12,13 Quantitative data on cider terroir and statistical analyses to determine its effects on sensory profiles are leagues behind. Investigations of cider’s geographic variability within a modern terroir context took place just a few years after the establishment of the first cider GIs14,15. The modest body of research that has since accumulated injects a useful dose of objectivity into an aspirational, yet often nebulous conversation.

First and foremost, the science shows that variety is typically the greatest driver of differences in cider chemistry16,17 and even when the variety or blend is held constant, the result can drastically differ depending on the production methods used. The One Juice Project in 2019 is an excellent example of this, with five makers transforming fifths of a single batch of 80:20 Dabinett-Browns juice from Ross on Wye into five stunningly different ciders.

Nonetheless, geographic variation within the same variety is also apparent, even without chemical analysis. Early English pomologists espoused around which villages Herefordshire Redstreak grew best. In the 20th century, Leonard Luckwill and Alfred Pollard proposed that Blakeney Red, once maligned as ‘abominable trash’ by Hogg and Bull, was a victim of terroir. The Forest of Dean supposedly bore much more amenable growth conditions for perry production than its Severn Valley homeland.

Contemporary analyses now show that chemical differences within the same variety can be statistically significant at multiple spatial scales16-20, supporting historic assertions regarding geographic variation. The impact of varied conditions between growing locations on fruit growth and juice chemistry is also relatively well understood in broad terms. We can reasonably expect the same variety grown in Herefordshire versus Hardanger to differ substantially due to climatic differences.

Terroir undeniably exists. What is rarely determined is the degree and balance of causality between variation in cider chemistry and the physical, ecological and human components of its terroir, or if such variation leads to typicity, the formal term for palpable differences arising from terroir. While a mass spectrometer can sift a cider molecule by molecule, human palates are less sensitive. Little Pomona’s Taste of Dabinett captures precisely this issue. Adam reports that he could not confidently ascribe the variations between same-vintage single variety ciders solely to orchard terroir, markedly different as they were.

Research by Dr Madeleine Way, previously of the University of Tasmania, lies at the cutting edge of these problems. Her work shows that ciders of the same variety, but grown in different terroirs can display statistically distinct differences in their human-ascribed flavour profiles.21 She has also shown that climatic variation between growing regions explained the majority of the chemical differences in ciders produced from the same variety.22 Terroir can lead to typicity, but a lot of hoops must be jumped through first, and other sources of variation are expected to play greater roles.

Physical factors like climate and soils are often the most straightforward to quantify with the right map, but they are just part of the problem. Substantial research effort has been devoted to understanding the microbiology of cider-making, largely from the perspective of ensuring industrial consistency, but this almost never intersects with any notion of regional variation. eDNA metabarcoding to characterise the microbiota of an orchard or cider press is an expensive and involved process at the end of day, compared to a quick glance at a topographic or pedological map.

Two recent studies showed that significant differences in microbial community compositions persisted into the early stages of fermentation in Pays d’Auge ciders produced for Calvados23, and ciders from New York’s Hudson River Valley.24 Otherwise, this is a drastically under-researched problem despite good reason to suspect that microbial terroir should have a major influence on cider character, at least for wild fermentations.

Beyond environment and ecology, management choices like root stock type, planting density, cultivation strategy, tree age, or even harvesting position on a single tree are all proven to affect sugar and phenol content in apples.25 Where do we draw the line to say whether these are part of terroir or otherwise? Then there is vintage variation. Dr Way’s work found that regionality was only a statistically significant effect for one growing season, but not in the following year.22 Add in the potential impact of strongly biennial-bearing varieties and the problem becomes more complex still.

Finally, there is the matter of scale. Terroir is ultimately a geography problem, Tobler’s Law through the lens of the tasting glass. For wine, microterroir might distinguish between individual vineyards or even rows within the same vineyard, while macroterroir would apply in the context of Bordeaux versus Burgundy. Should we really expect terroir to be readily discernible between two adjacent orchards if they differed solely in their slope and aspect, holding all other factors constant?

It is useful then, to consider why typical formulations of terroir work well for wine but perhaps fail to carry over into cider. Wines will typically use no more than a few varieties and GI-controlled products are even more stringent. Chablis can only be made from Chardonnay, or Burgundy reds from Pinot Noir, and their production methods also are tightly regulated. Differences in climate and soil between vineyards, and microbial terroir in the case of natural wines, has a greater opportunity to influence wine production in ways that persist from press to palate.

Cider and perry GIs on the other hand are not as stringently bound. Asturian and Basque PDOs are prescriptive in production methods but still permit dozens of varieties in any desired proportions. English and Welsh PGIs only require that traditional bittersweet or bittersharp varieties are used, of which there are hundreds. The variation they introduce largely relegates terroir to a second order effect, notwithstanding the additional differences arising from tree age and the like.

Beyond terroir-driven approaches by individual makers, perhaps the only examples where terroir might be more readily observable on broader scales are in Brittany’s Royal Guillevic ciders and Normandy’s Poire Domfrontais. Widely produced across Morhiban, Royal Guillevic is very rarely, if ever, blended with other varieties, while minimally 40% of the juice in Poire Domfrontais must come from Plant de Blanc and in practice, makers use a much higher percentage still. These instances, however, are far from the norm.

The conclusion we face is that which statisticians often run into – the data says we need more data. Yet the picture we have so far suggests that seeking typicity with the same fervour as for wine may lead us into a blind alley.

A future of opportunity

Producers the world over are talking about terroir, so it clearly matters to the cider community even if the science offers a more conservative stance. At some level, terroir can provide insight into cider character. Differences in varieties and production methods may matter more to organoleptic profiles overall, but this does not close the door to typicity. Still, this conceptualisation of terroir bears idiosyncrasies from wine which do not readily map onto what cider has to offer.

Adam has raised a further pertinent point. Many consumers will not care about terroir or know what it is.26 Even when GIs enter the picture, they are more concerned with authentic purchases that support and are supported by cultural heritage, rather than with the landscapes which underscore production or how they might generate typicity8. We care that our Parmigiano Reggiano is produced in Emilia Romana or our apfelwein in Hesse, but think little of the regions themselves. What terroir’s protracted evolution shows, however, is that the terroir conversation never really matures. Instead, it simply shifts focus and with these shifts lie exciting opportunities for cider’s future.

Chris’ brilliant article on rethinking terroir for the 21st century provides the perfect starting point for this new line of thought. Terroir is not just cider arising from natural setting, free from human intervention. It is the reciprocal relationship between the land and those who cultivate it. Terroir therefore invites us to engage with a question critical not just to cider and orchards, but to agricultural systems globally – what is our relationship with the land? In turn, this act of reflection creates the chance to redefine what that relationship with the land is.

Firstly, regard for terroir contextualises and acknowledges the essential cooperation of the maker with their setting. The best ciders do not arise simply by letting nature take its course. Skilful cultivation and diligent production are required to best express the fruit from any setting. Working with terroir is just as much a part of this process, even if producers themselves are not terroir-driven or bound by AOC-styled prescriptiveness.

At broader scales, specificity of terroir will naturally decrease. Larger areas encompass greater variation in slopes, elevations, microclimates and soils. Yet the sum of these conditions still governs fruit development and even its evolution. This is perhaps why distinguishing between varieties and terroir at the scale of historic cider regions sometimes nags at me even though it is often sensible to do so.

Most varieties (excepting cultivars from deliberate breeding programs) are a product of a region’s climate, topography and soil interacting with a wild genotype. John Eveyln spoke of the Turgovian pear rather than the Swiss fruit forests where it originated, but those forests remain integral to its story. In turn, regard for terroir at regional scales must shift towards its spatially and temporally broader relationships with cider cultures. Endemic varieties and production heritage may be the major differentiators of cider character between Asturias and Herefordshire, but their distinct terroirs shape both elements.

By seamlessly spanning scales of time and place, terroir is a powerful distillation of identity for individual makers or entire regions alike, rather than just a forensic tool to tease apart organolepic character. It lets us connect holistically with the landscapes in which ciders and perries are necessarily rooted, whether in a single vintage from Nightingale in Kent or the gamut of perries from the Mostviertal. We talk of cider because terroir exists, not the other way around.

I suggest, then, that seeking typicity above all else risks missing the full scope of what terroir means to cider. We need not cast it aside entirely, but we should place less emphasis on it. It can work for wine, but it is less suited to what cider has to offer. By discarding the trappings of wine where appropriate11 and reshaping terroir to emphasise the aspects that matter most to its community, it could be the perfect canvas on which to capture the wider picture cider has to offer, Cider is not wine, so its terroir discussion need not try to mimic that of wine too closely.

The destruction of orchards across Europe in the 20th century is a stark warning to how regionality and biodiversity can decline hand in hand when we forget about our relationship with the land and lose sight of terroir. The opposite, however, must surely also be true. Set against the steel-clad, industrial uniformity of macro cider and the creeping erosion of traditional orchards, terroir cuts to the heart of aspirational cider’s vital relationship with these unique oases of biodiversity that punctuate more heavily managed agricultural landscapes.

Traditional, low-density orchards, the terroir of UK fine cider, are a priority habitat for conservation, as are the meadow orchards (streuobstwiesen) of Hesse and Baden- Württemberg, or the biodiverse bocage landscapes of Normandy’s cider country. Cider production provides a powerful conduit for their conservation, particularly when GIs come into play and neatly packages its terroir into a focus for actionable change27. I suspect that the average consumer will care more about terroir from this perspective compared to if shelly limestone creates a slightly more phenolic profile than a loess-flecked clay. Recognising terroir’s value in this way can only add impetus to supporting orchard conservation.

Conservation, of course, is not strictly unique to cider. Managed with ecologically friendly methods, vineyards can also support greater biodiversity. Orchards, however, ultimately bear greater capacity to do so.28 This exemplifies how, informed but unanchored by the wine’s preconceptions, cider can embrace formulations that only it can offer. Through AOCs, terroir revitalised the reputation of French wine in the previous century. Through its links with culture and biodiversity, terroir could be the key to cider’s sustainability not just today, but well into the future.

Fringing the temperate margins of the North Atlantic, cider cultures historically benefitted from two intervals of reliable winter chill, the Medieval Warm Period and the Little Ice Age. Cider today still relies on varieties which evolved in a much cooler world, and even newer, non-traditional varieties still bear the genetic legacy of their temperate ancestors.

Climate instability now plays Russian roulette with harvests year on year, and the halos of mid-latitude temperate conditions where apple cultivation is viable shrink polewards. We face unavoidable questions about cider’s future in a warmer Anthropocene world. The conversation of how best to safeguard cider production is taking shape, with producers in Britain and America seeking to identify climate resistant varieties and rootstocks. Posterity Ciderworks are already experimenting with what will grow best in the climatically extreme frontier of California, and Artistraw are grafting French varieties in the hope of future-proofing production in their slice of the Wye Valley29.

From an ecological perspective, however, identifying varieties that may prosper under a changing regional climate is one side of the coin. Terroir is the other. Viticulture, benefitting from a decidedly greater coupling of market interest and research investment, emphasises this point. Comparison between regions – i.e. between terroirs – is essential to navigating the Anthropocene, rather than examining the performance of varieties in geographic isolation30-32.

Some crops grow better in some places than others. Terroir is what lets us understand why, empowering us to predict how our planting patterns must match how the distribution of the terroirs which support cider cultures the world over will shift with the changing climate. This even extends to production methods. Natural cold is becoming an increasingly unreliable element of the Quebecois ice cider PGI and ice cider production in Vermont is also feeling the pinch.33 Keeving, a hallmark of many French and West Country producers, similarly relies on cool conditions which will inevitably shift with climate change, forcing technological intervention or a fundamental shift in production method.

To secure cider’s future, it is as much about looking polewards for where the terroirs we currently understand will travel, as much as looking to lower latitudes for varieties more resilient to warmer conditions or the host of parasites and pathogens this brings. Could traditional English bittersweets, historically nourished by the mild climates and red soils of Herefordshire find solace not just on Scotland’s Black Isle, where cider has also taken root, but goes all the way up to Caithness along the ancient margins of the Old Red Sandstone continent? Could Kentish Discovery find its way to the Yorkshire Riviera as the climatic conditions currently found in the Garden of England shift northwards onto the same chalk soils that span from Skegness to Scarborough? Just where will our terroirs go?

Embracing change

Climates and landscapes shift across decades and geological epochs. The physical bounds on which we define terroir are just the latest episodes in a much longer biological and historical narrative. All language evolves too, and terroir is no exception. With their veneer of grand tradition, it is all too easy to lose sight of the fact that French wine makers drove a major shift in terroir’s conceptualisation only rather recently. Historically, climate change and pestilence forced viticulturalists to work with whatever grew well at the time. AOC strictures are less than 100 years old and changing climates are already forcing similar concessions and revisions to its formulas.2

In the cider world, the winds of change are also stirring, as much from aspiration as from climate emergency. To say that a reimagining and reapplication of terroir violates the ‘proper’ definition defies the nature of language itself. Rather, it shows that terroir can keep evolving to remain relevant, as it is has done time and time again. By clinging to its current guise, we would end up like King Canute, waist deep in a tide of changing definitions or inundated beneath waves of environmental change. The last thing we can afford to do is to simply let nature take its course or allow the conversation to stagnate.

Terroir’s meaning was once territory, then agricultural land, then the link between land and product. All are true. Cider terroirs are those territories which allow these remarkable drinks to exist, the unique agricultural landscapes where orchards and cider-makers co-operate to produce endless, delightful fermentations of pomme fruits. It is aspirational, a common call to recognise everything which makes cider so special, and an invitation to innovate and craft new identity. Terroir must inevitably adapt. We need simply to choose what cider’s terra incognita will look like.

Bibliography

In addition to the past Cider Review articles and sources referred to directly in this article, below are some of the sources which support or shaped the views presented in this article.

- Parker, T. (2015). Tasting French terroir: the history of an idea. University of California Press, 248p

- Phillips, R. (2016). The myths of French wine history. guildsomm.com/public_content/features/articles/b/rod_phillips/posts/french-wine-myths

- ‘Terroir’ – CNRTL Lexical Portal. cnrtl.fr/etymologie/terroir (accessed 23/01/26)

- Embrey, G. (1891). A comparison of English and American cider, with suggestions for estimating the amount of added water. The Analyst, 16: 41–45

- Allen, A. (1902). A contribution to a knowledge of the chemistry of cider. The Analyst, 27: 183–192

- Charters, S., Harding, G. (2024). The irresistible rise of the notion of terroir. Journal of Wine Research, 35: 235–252

- Droin, C. (2024). The expression of specific terroirs in Calvados, identified by three Appellations. velier.it/en/calvados/6309-the-expression-of-specific-terroirs-in-calvados-identified-by-three-appellations.html

- Teuber, R. (2009). Producers’ and consumers’ expectations towards geographical indications – empirical evidence for Hessian apple wine. European Association of Agricultural Economists, 113th Seminar, Chania, Greece

- Friedrich, J. (2002). When fine French ‘wine’ is cider. saveur.com/article/Wine-and-Drink/When-Fine-French-Wine-is-Cider/

- Hrechdakian, S. (2016). Cidermakers search for apple terroir in the Finger Lakes. medium.com/@foodrepublic/cidermakers-search-for-apple-terroir-in-the-finger-lakes-bf10bb5460a

- Maker, M. (2023). Cider can learn from wine’s lexical missteps. makerstable.com/p/cider-can-learn-from-wines-lexical-missteps

- Ballester, J. (2020). In search of the taste of terroir: a challenge sensory science. XIIII International Terroir Congress, Adelaide.

- Brillante, L. et al. (2020). Unbiased scientific approaches to the study of terroir are needed! Frontiers in Earth Science, 8: 539377

- Travers, I. et al. (2000). Influence of terroir and orchard management on the composition of cider apples. [Influence du terroir et de la conduit du verger sur la composition des pommes a cidre]. IVES Conference Series, Terroir 2000

- Laplace, J. et al. (2002). Incidence of land and physicochemical composition of apples on the qualitative and quantitative development of microbial flora during cider fermentations. Journal of the Institute of Brewing, 107: 227–234

- Merwin, I. et al. (2007). Cider apples and cider-making techniques in Europe and North America. Horticultural Reviews 34: 365–415

- Thompson-Witrick et al. (2014). Characterization of the polyphenol composition of 20 cultivars of cider, processing, and dessert apples (Malus × domestica Borkh.) grown in Virginia. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 62: 10181–10191

- Perestrelo, R. et al. (2019). Untargeted fingerprinting of cider volatiles from different geographical regions by HS-SPME/GC-MS. Microchemical Journal, 148: 643–651

- Medina S. et al. (2019). Differential volatile organic compounds signatures of apple juices from Madeira Island according to variety and geographical origin. Microchemical Journal, 150: 104094

- Sousa, A. et al. (2020). Geographical differentiation of apple ciders based on volatile fingerprint. Food Research International, 137: 109550

- Way, M. et al. (2022). Regionality of Australian apple cider: a sensory, chemical and climate study. Fermentation, 2022, 8: 687

- Way, M. et al. (2024). Cider terroir: influence of regionality on Australian apple cider quality. Beverages, 10: 99

- Misery, B. et al. (2021). Diversity and dynamics of bacterial and fungal communities in cider for distillation. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 339: 108987

- Perron, G. et al. (2025). Orchards and varieties shape apple and cider local microbial terroirs in the Hudson Valley of New York. Fermentation, 11: 369

- Kviklys, D. et al. (2022). Apple fruit growth and quality depend on the position in tree Canopy. Plants, 11: 196

- Charters, S. et al. (2021). ‘It’s a small, yappy dog’: The British idea of terroir. IVES Conference Series, Terroir 2020

- Quiñones-Ruiz, X. et al. (2017). Why early collective action pays off: evidence from setting Protected Geographical Indications. Renewable Agriculture and Food Systems, 32: 179–192

- Katayama, N. et al. (2019). Biodiversity and yield under different land-use types in orchard/vineyard landscapes: a meta-analysis. Biological Conversation, 229: 125–133

- Cawood, C. (2025). Seeds of change: cider and climate change. drinksretailingnews.co.uk/seeds-of-change-cider-and-climate-change

- Ducarme, F. The ecology of the ‘terroir’. Environmental Ethics, 47: 65–88

- Wolkovich, E. (2025). The problem of terroir in the anthropocene. Harvard Data Science Review, 7: doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.d605e50f

- Wolkovitch, E et al. (2025). Building a more predictive model of terroir for the Anthropocene. Plants, People, Planet, 7: 611–1620

- YCC Team (2023). Warming winters threaten a unique dessert cider. https://yaleclimateconnections.org/2023/11/warming-winters-threaten-a-unique-dessert-cider/

Cover image: a cider orchard in blossom, Herefordshire, 2013. Image by Les Haines. Reproduced under CC-BY-2.0.

Discover more from Cider Review

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

An astonishing, comprehensive, brilliant article. Thank you for the read. I will surely need to revisit and ponder for some time.

Just to address one quick point: “Should we really expect terroir to be readily discernible between two adjacent orchards if they differed solely in their slope and aspect, holding all other factors constant?”

We grow Kingston Black in 3 orchards all within 1 mile of each other, each a different aspect, though similar slopes. Each is harvested and fermented separately. The result is three distinctly different ciders with clear tasting notes that speak to their provenance. To my surprise, the youngest trees, albeit in the most advantageous location, produce the best cider.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Delighted you enjoyed the article! And many thanks for adding the note about Kingston Black across your orchards – really cool to hear that there are some compelling vintages out there for experiencing small-scale terroir variation. What bottles are those single-orchard-KBs, specifically? I’d be super keen to snag some from your site if possible. Cheers!

LikeLike

Thanks Joe for the excellent article.

LikeLike