The internet is rife with misinformation. Well, it probably always was, but at the moment it feels like it’s reaching a zenith. Though it is of little consequence compared to what we see growing in our social media timelines, it’s true to say that cider is not immune to small-scale disinformation. Or perhaps misinformation is the better word, as oftentimes it is due to simply believing and then sharing well-intentioned but false information. A case in point: the belief that cyder with a y was historically a distinct and better product than cider with an i.

In early 2024, during an Instagram Live session focused on cider (when that was still a thing), one presenter sampled a drink branded as ‘Cyder’. The use of this olde worlde spelling is occasionally encountered, typically intended to evoke the historic tradition associated with cider, which is fair enough. However, the presenter proceeded to clarify that the spelling distinction reflected historical practice: ‘Cyder’ with a ‘y’, he said, traditionally referred to a full-juice drink comparable to wine, whereas ‘cider’ with an ‘i’ denoted diluted beverages regarded as inferior by comparison.

My initial reaction was that it was just nonsense. Well, I used a different word. It sounded like stuff made up by a marketing team, but apparently it was in a book. So, I suspended my disbelief till I could buy the volume mentioned and check the original sources, as one does. Well, as I do.

But it was familiarity with old texts that caused my initial disbelief. In my literary travels through cider and especially perry history over the past five years, I’ve trawled through a lot of antiquarian English literature, and German, Swiss and Austrian too, noticing how the terms for these drinks changed over time. There was a period from the mid-18th to the mid-19th Century, for example, where German texts would refer to Apfelcyder or Birnencyder interchangeably with Apfelwein and Birnenwein, sometimes in the same chapter. Eventually the latter two took over as the general default here, but we are also blessed with regional differences. English was no different, and it took some time before things became a little more consistent, although, as we will see, there was some flip-flopping over the course of more recent centuries.

The book referenced by most makers that claim ‘cyder’ is something distinct from ‘cider’ is Roger Kenneth French’s The History and Virtues of Cyder, published in 1982. French was a respected author and historian of medicine, known for his considerable scholarly contributions to the understanding of medical history and its intersections with cultural practices. He delved into the evolution of health-related traditions and the ways in which historical perspectives shaped contemporary views. But he also had a deep interest in, and made his own cider, so applied the same thoughtful approach to this drink.

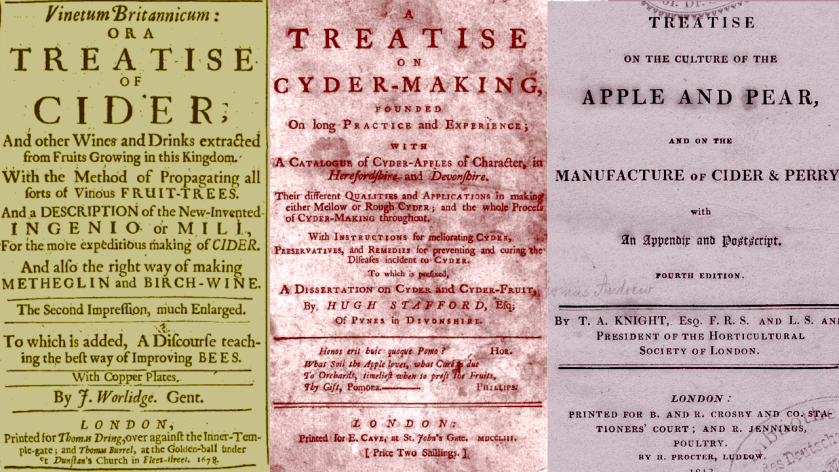

The History and Virtues of Cyder is an impressive work, with lots of interesting detail on how cider was made, perceived and how it changed over the centuries in the context of Great Britain. However, the premise that it opens with is that going back centuries, cyder was a different and distinct drink from cider. An assertion that seems to be increasingly doing the rounds today. Aside from not having specific references to support this rather fundamental claim, the premise is rather spoiled by French’s use of the title image of Worlidge’s 1678 book, Vinetum Britannicum, or A Treatise of Cider and other Wines and Drinks extracted from Fruits Growing in this Kingdom. It’s there in the title! The first 30 or so pages feel like a barrage of information that often includes quite generous interpretations of the source material to support the claim. Despite over 100 endnotes for this part, there is no reference explicitly defining a difference between cyder and cider, it is rather interpolated.

I started writing this article in April 2024, right after that Insta Live presentation, but to be honest, it didn’t feel right to rail against such a prodigious mind, so I parked it as unimportant. Until three weeks ago, when Adam sent me a screenshot of yet another maker’s website, making the claim that, and I quote, “traditional cyder is made from a single pressing of vintage fruit, rather like ‘extra virgin’ olive oil. Cider is made from the Cyder pulp being rehydrated & pressed again”. Adam’s accompanying comment was that he was sending it to troll me shamelessly, and it worked. Just two weeks ago a similar claim was repeated in The Times, so I can’t let it go.

So what did French actually say in his book? It’s in the introduction and first chapter where the premise is set, and from then on it is assumed that Cyder is the real, full-juice McCoy, while cider is a watered-down form, whether post- or pre-fermentation, as in the case of ciderkin.

The introduction opens: ”Cyder is no longer made… We are all familiar with pasteurized, diluted, bland and carbon-dioxide-injected cider, but cyder is a living wine of some subtlety, matured in cask and bottle in the manner of champagne (French, 1982).”

Or short and sweet:

“… cyder was a wine, not a long drink (French, 1982).”

The implication being that cider is a long drink hence low in alcohol. Several times, French also ties cyder to class:

“The tradition of making real cyder died when gentlemen stopped drinking it. Cider is still made by isolated individuals in various villages in the West Country today, but invariably the product is at least half water: it is the survival of what the farmhands and household servants drank, but in no sense is it real cyder (French, 1982).”

Or:

“… the old cyder which demanded the first use of the fruit is no longer known, and the class of people who drank it then are largely gone, or drink wine (French, 1982).”

It’s certainly true that cider was (once again) in a state of decline at the time of French wrote those words, and that more industrial-produced cider was likely to the fore. But to differentiate between cyder and cider as meaning two different things? I don’t think the evidence supports it, so let’s look a little deeper at the usage of the words cider and cyder in Britain over the past five centuries or so.

16th Century

Within English literature, early texts seem to use mostly ‘sider’, though it would appear that by the end of the 16th Century literature was generally split between ‘sider’ and ‘cider’. Both with an ‘i’. But there were exceptions of course, and it has to be said, it was a bit like the Wild West when it came to spelling convention, with cyder, cider, sider, cidar, cicer and pommage featuring in texts of the time (thank you Elizabeth!). But let’s look at some of the cyders.

In 1575, Leonard Mascall published a book titled How to plant and graffe all sortes of trees. As the title suggests, it was focussing on propagation, but of course reference was made to cider and perry. On page 74 he talks about “Cyder and Pyrrie, Pirrie”. But bear in mind, many words we now spell with an ‘i’ now were once spelled with a ‘y’. For example, the author refers to “cynamon and such lyke”.

The 1600 Maison Rustique Or The Countrie Farme, an English translation of a French book (this may become relevant later) also uses the terms “Cyder” and “Perrie (from peares)”. I am not a linguist, but I understand that y was once considered a separate vowel with its own sound, but as pronunciation shifted, adopted a sound more akin to i, hence the seeming interchangeability in some periods. Interestingly, the 1616 reprint changed to cider with an ‘i’ as the default.

As French claimed that diluted drinks were spelled with an ‘i’, how were they named in this period? Watered-down cider was sometimes referred to simply as water-cider, but more often as ciderkin. Sure, with an ‘i’, but it was following the convention that the full-juice drinks were also spelled with an ‘i’, and these were just diminutives of that. So in this Century, it’s fair to say that the majority of mentions of our favourite drink followed the ‘i’ spelling, which I will illustrate later.

17th Century

The 17th Century is often considered the golden age of English cider, and indeed, there was an explosion of works related to the drink, as things got more scientific and ordered, and there was a real push to develop cider into an English wine. As a result, there is a wealth of literature to dive into for evidence.

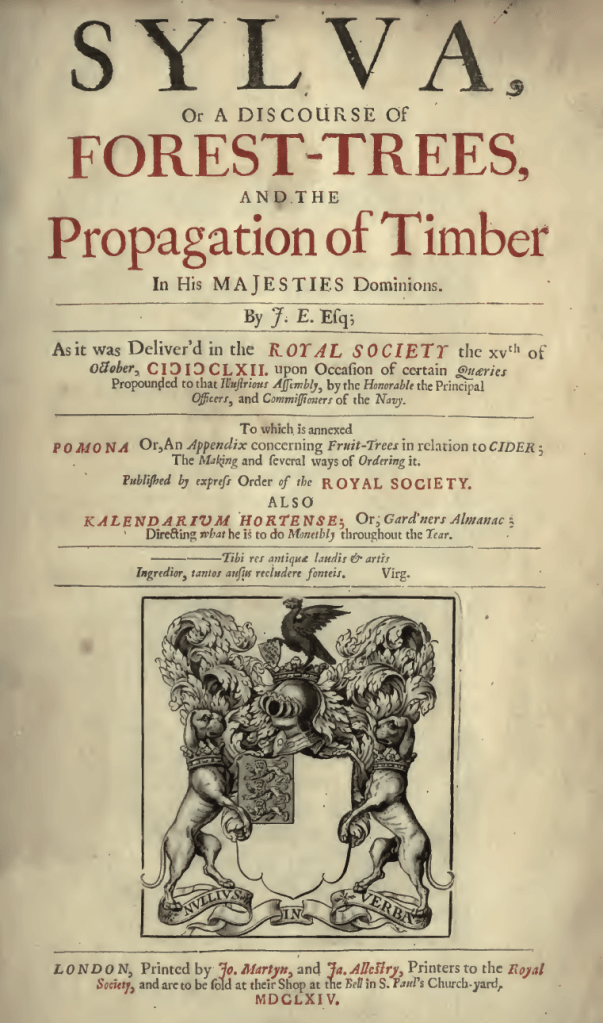

In the most famous early tome on cider and the fruit surrounding it, John Evelyn’s Pomona, an Annex to his Sylva originally published in 1664, the author makes 393 mentions of cider and 3 of cyder. And two of those three were in the index! And this in the golden age of Cider! I should rest my case there.

But what about this claim that cider with an i was an inferior watered down drink compared to cyder with a y? Well, not quite true. Mixing water with the pomace and pressing again goes back a long time. Ciderkin in English is akin to piquette in the wine world, producing a refreshing, low alcohol drink that was reputed to have been consumed in quantity by farm labourers on hot summer days. Our antiquarian authors had much to say on the topic, and it would seem that adding water to cider was quite traditional and not at all seen as making something inferior.

In an addendum to Evelyn’s Pomona, ‘General Advertisements concerning Cider’, Reverend Dr. John Beale, one of the most influential early… well, influencers regarding cider, describes adding water to the apples while grinding, claiming it yielded a pleasant drink. “…far more pleasant than adding water in the glass, like adding salt to beef on your plate is not half as much relish as that seasoned in a timely manner while cooking”. But he still called it cider, not at all differentiating from the 393 other mentions of the word cider with an ‘i’ in the preceding Pomona text.

In the second edition of the same volume, published in 1670, Daniel Collwall also wrote an addendum, ‘An Account of Perry and Cider out of Glocester-Shire’ in which he wrote “When the pressing is finished , they take out the fruit, and put it into a great vat, pouring several payls [I chose not to update that spelling] of water to it, which being well impregn’d, is ground again slightly in the mill to make an ordinary cider for the servants. This they usually drink all year about”. Again, consistent spelling with the full juice version that was consistently spelled cider.

In ‘Observations Concerning the Making, Preserving of Cider’, John Newburgh Esq. describes how on the islands of Jersey and Guernsey, which were apparently known in the Kingdom for the quality of their cider, that it was normal practice on those islands to add a pail of water to a hogshead of cider. So much so, that the locals would say that an undiluted cider was counterfeited.

Worlidge, another cider luminary of the time, also wrote of ‘water-cider’ in his 1678 Vinetum Britannicum or A Treatise of Cider and other Wines and Drinks extracted form Fruits Growing in this Kingdom. Yes, the one French used as a frontispiece. He describes the making of Water-Cider, which he says is usually called Ciderkin or Purre. Interestingly, Worlidge also states that such ciderkin can be a replacement for small beer, itself made from the last runnings from a mash, and so being lower in sugars and hence alcohol. Paralleling the small beer concept, he also mentioned that the ciderkin can be made to keep longer by boiling it with hops after pressing.

Worlidge was firmly in the cider with an ‘i’ camp, as his book contains over 360 mentions of cider, and only 1 of cyder. So, it’s probably safe to say that in the golden age of British cider, the luminaries of the day predominantly spelled cider with an i, regardless if it was full juice or mixed with water in some way.

18th Century

It was in the mid-18th Century that the spelling of cyder with a y seems to have first come into fashion. But why?

It certainly had nothing to do with being a distinct way of making, or single pressings of vintage fruit – another term in need of explanation, though I know Gabe Cook was looking at it, so I will forego an explanation here. I rather suspect, but can’t prove (in this century), that it was more likely to do with national chauvinism, wanting to distinguish British cider from French Cidre. From 1744 there was yet another bout of Anglo-French wars, lasting to the end of the Century, after a break since 1713. In the previous Century much was said about making cider and perry a British wine to reduce the reliance on wine imports from the Continent, but the spelling hadn’t bothered them that much.

But perhaps John Philips’ 1708 Cyder: A Poem In Two Books had some influence, as it was hugely popular, even being translated to Tuscan. Philips of course used the cyder spelling throughout, but he also spelled the word scion as cyon.

Batty Langley. I love that name. I once mistakenly sent off an e-mail with my own name signed off as Batty, which may have been foreshadowing. In 1729 he published Pomona: or the Fruit Garden Illustrated. His cyder score was 60 to cider’s 0.

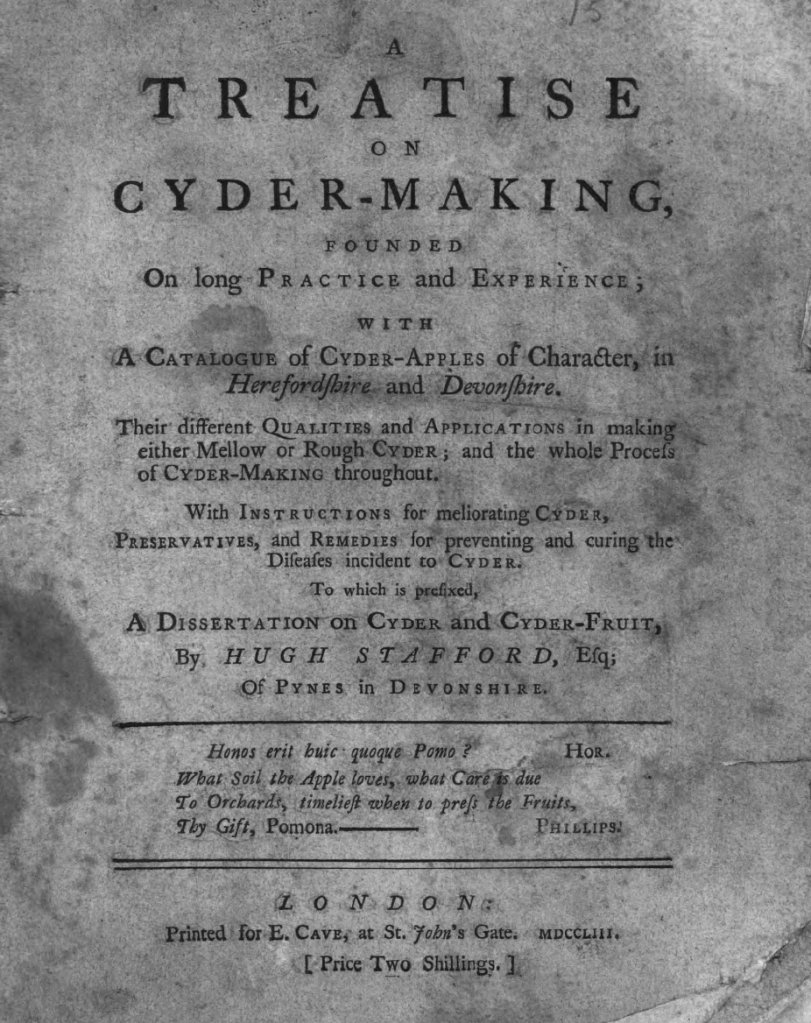

Hugh Stafford published the definitive book on cidermaking in 1753. Certainly, one of the most detailed description in that Century. In A Treatise on Cyder-Making he of course made use of the cyder spelling throughout, 307 mentions in total. But he also describes the addition of water to cyder in two sections, one to the pomace when pressing, to make what he referred to as “Water-Cyder”, the same as Worlidge’s water-cider and what we’d call ciderkin today. The other related to adding a pail of water to each hogshead of cider to “dilute and set its parts more quickly at liberty”. He goes on to say that this makes the best Cyder. So again, diluted with water, but still called cyder with a y, breaking the idea that cider was a diluted drink but cyder was not.

But just one more note on this Century, triggered by a comment from Elizabeth Pimblett of the Museum of Cider when she kindly cast an eye over this text. In 1755 Samuel Johnson published what might be considered the first comprehensive, modern dictionary of the English language, which should have had an effect of standardising spelling. Did he favour cyder as the true British spelling, leading to the increase we see in this Century? He did not. In both the 1755 and 1773 editions he used cider, defining it as “the juice of apples expressed and fermented”.

19th Century

The 19th Century saw a blossoming of interest in all things apple and pear, as a more rigorous and scientific interest in pomology took over. I have written before that British pomology and cider making were inextricably entwined, so it would not be amiss to turn to the great works of the time to see how they treated the words cider and cyder. By the time a quarter of the 19th Century had passed, it seems that cyder was out of fashion, being replaced again with the older cider spelling.

Though I am sorely tempted to go into great detail here, let’s just summarise the number of mentions in the most influential cider and pomology works of that Century.

| Publication | Cider | Cyder |

| 1811 – Pomona Herefordiensis T.A. Knight | 52 | 2 |

| 1813 – A Treatise On The Culture Of The Apple &Pear T.A. Knight | 97 | 0 |

| 1851 – British Pomology Robert Hogg | 91 | 15 |

| 1876-1885 – The Herefordshire Pomona Robert Hogg and Dr Henry Graves Bull | 175 | 7 |

| 1886 – The Apple and Pear as Vintage Fruits Robert Hogg and Henry Graves Bull | 576 | 28 |

I could go on, but suffice to say, in this century, cider with an ‘i’ was back in fashion. But not everyone was happy with that, even when it was used for a movement that aimed to promote cider

Charles Wallwyn Radcliffe Cooke, often referred to as the “MP for Cider,” was a prominent advocate for cider production in Great Britain. As MP for Hereford in August 1893, it was even more fitting. In March 1895, Radcliffe Cooke made a presentation to the Royal Society about cider, where he opened with the line “cider is the expressed and fermented juice of the apple : perry the expressed and fermented juice of the pear. I should have thought it unnecessary to mention these elementary facts had I not discovered, even among persons who would be much nettled if they were not regarded as well-informed, a surprising degree of ignorance on the subject”.

Plus ça change!

However, more relevant for our theme is the discussion following the presentation, where the Chairman of the Society went off on a bit of a rant, here with my emphasis:

“… considering the exhaustive manner in which Mr. Radcliffe Cooke had, in his admirable paper, treated the technical and economic aspects of the cyder industry of the United Kingdom, and that the meeting would be further addressed on these heads by several cyder makers present, his own remarks would be of the nature of a light interlude, dealing with points of general interest connected with the not less fascinating than important subject of Mr. Radcliffe Cooke’s most practical and invaluable paper. In the first place, he did protest against Mr. Radcliffe Cooke spelling cyder with an ‘i’ – cider. They all did it – the Times, which had done so much in promoting the beneficent movement headed by Mr. Radcliffe Cooke, and had always treated him (the Chairman) with exceptional consideration, persisted in doing it, and nearly all the cydermakers in the country did it.

But there was no manner of excuse for it, and spelling the word with an ‘i’ really took the best part of the savour and the goodness out of cyder. The pedigree of the English form of the word is usually traced from the Hebrew shekar, through the Greek sikera, the Latin sicera, and the French cidre to cider. And this is correct enough. But , like so many other ancient words in the English language, cyder has a complex etymology, and originates in the Latin sisera, and Spanish sidra, and Italian cedra, as well as in the French cidre”.

Essentially, a bout of National Chauvinism, seemingly trying to tie cyder more to a Latin origin, but it counted for nothing; the days of spelling cyder with y had long expired, and cider with an i, as it had been over 100 years earlier, had long returned.

High Tech Tools and the Big Picture

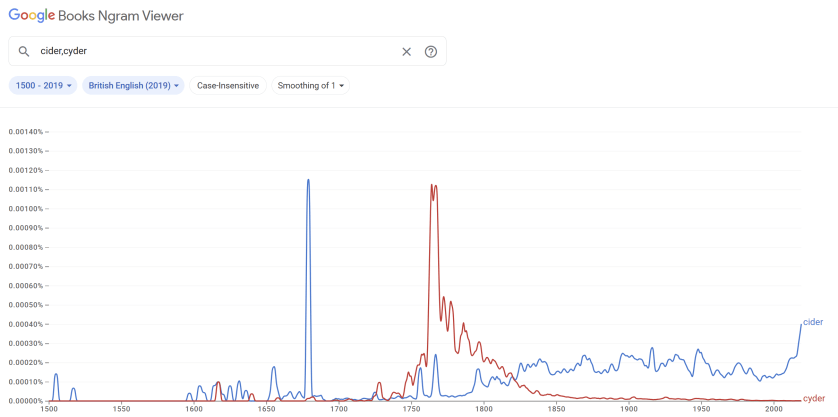

Sometimes a picture can paint more than a thousand words, and in this case, we can illustrate my counterargument using a simple graph from Google Books Ngram Viewer. This is a powerful tool that allows users to search for the frequency of words or phrases in a vast corpus of digitised books spanning several centuries. By entering specific terms, one can generate a chart that visually represents how often those terms appeared in published literature over time. This makes it particularly useful for tracking historical changes in language, spelling, and cultural trends. In this case, I used it to reveal when certain spellings, such as ‘cyder’ versus ‘cider’, were most popular, providing an insight into how these words shifted over time.

This Ngram chart is a great representation of the shifting popularity of the spellings ‘cyder’ and ‘cider’ over several centuries. It shows that prior to 1750, ‘cider’ and ‘sider’, both with an i, were the dominant spelling, with “cyder” appearing only rarely. A large spike of cider around the mid-1600s reflects that golden age of cider, when far more writing was being done about this topic.

Beginning in the mid-18th century, there is a noticeable surge in the use of ‘cyder’, peaking between the 1750s and ending roughly 1825, a period when this spelling gained significant traction. Why, I cannot say, perhaps simply influenced by linguistic preferences, perhaps partially by national sentiment. But I can say that the spike in the usage of ‘cyder’ seems to align with an increase in published documents, many of which appear to be related to tax and legislation, perhaps not surprising with the Cider Tax having been introduced in this period of 1763 till it was repealed in 1766. If there was a preference for ‘cyder’ in this period, the signal in the graph is also amplified by the expansion of printed material during that era, and it being a hot topic at the time.

After 1825, the prevalence of ‘cyder’ declines sharply, while ‘cider’ regains dominance and continues to be the preferred spelling through to the present day. Essentially, we can say that the brief ascendancy of ‘cyder’ was a historical anomaly, with ‘cider’ remaining the enduring standard in English usage, and that counts for both full juice and diluted variations over the years.

Conclusion

Look, it’s ok to use the word cyder on your label to make it stand out from other bottles on the shelf. There have been many ways to spell cider over the centuries, and all are valid. But it is simply not true to claim that, historically, cyder and cider were different drinks.

It’s probably fair to say that in 1982, R. K. French used the whole idea of ‘cyder’ being a different drink in two ways. First, as a kind of storytelling narrative, a way to tie everything together while keeping a separation between what we might call common and fine cider today. But also to keep things interesting. By using an old spelling and suggesting there was a real difference, he could mix in history, language quirks, and even a bit of national pride, giving a clever way to make the story hang together, adding a little drama, so readers remember it. It certainly seems to have worked! 43 years later it is being repeated.

At the same time, it’s also fair to say that by the 1980s people had likely largely forgotten what good, real cider was. The successive waves of pride in a British wine based on apples that we’ve seen over the previous three centuries was probably at an all-time low, so French was providing a timely reminder of what once was, and what could again be. It’s a call that echoes our own sentiments today.

Language changes and evolves, spelling changes too, in English probably more than any other living language. English has had many ways to spell our favourite apple-based drink, from cedir, cedyr, cider, cidre, cither, sider, sedir, seider, seyder, sider, sidre, sidur, sither, sychere, sydir, sydur, sydyr (thanks to Mark A. Turdo for this list). But none of these meant a different form or class of the drink, it is just the wonderful variability of this language we speak, developing over centuries, cross-pollinated by multiple incursions of language and culture.

So, I think it’s time to stop spreading misinformation. There’s enough heritage, cultural weight and gravitas behind the word cider, whatever way it is spelled. Makers can spell it as they wish, but there’s no need to make stuff up or repeat myths to justify it, or to inadvertently cast aspersions on makers that are using the accepted modern spelling as if it’s not the real thing. We are again living in a time where there is a true appreciation of full juice, artisanal cider, even if we are not toffs or of the landed gentry, and that’s what we should celebrate.

Wassayl!

References

French, R.K. (1982). The History and Virtues of Cyder. London, Robert Hale.

Discover more from Cider Review

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A most comprehensive and compelling article, Batty, which I have thoroughly enjoyed. I am particularly charmed by Dr Beale’s assertion that adding water prior to fermentation is widely like seasoning your beef. My father immediately remarked that this technique was something used in the early days of cidermaking here, in the late 1980s! How curious.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haahaa! Thank you Thomas! 😀

I very much enjoyed Beale’s simile, and it shows adding water is certainly not something new.

LikeLike

This is a great study! Thanks for sharing.

I also wrote about this, but took a slightly more orthographic approach. You can find it at https://pommelcyder.wordpress.com/2018/02/04/cider-by-any-other-letters-spells-as-sweet/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Mark, and thanks for your work too!

LikeLike

Thanks for the week documented and engaging exploration of cyder/cider. Your Ngram chart set my wheels turning, and I did some less-thorough explorations of my own. A bit of background first, though: I’m a Yank, but did my PhD in Philology at University of Edinburgh (Scotland, not Pennsylvania). I was made conscious of a stronger ‘nationalist’ sentiment about British English than we in the States tend to have. In reading your article, I wondered if the peculiar shift to ‘cyder’ in the mid -18th c. might have had some influence from the Dutch, who employ ‘y’ as a shorthand spelling for their diphthong ‘ij’.

It is interesting to note that in the early part of the 18th a previously close relationship between the Dutch and the French foundered as the two nations competed more and more fiercely for overseas territories and seafaring trade, which may have increased British sympathies for the Dutch. This would have been short-lived, as the Brits and the Dutch experienced their own tensions, leading to the Brits trouncing the Dutch in the 1780s.

Just a point of curiosity, rather than an actual hypothesis… but some of your readers may find other parallels to explore.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, David!

Yeah, I’m unsure about that, as I cannot imagine the British at the time adopting a spelling out of sympathy for another nation, especially one they had frequent spats with 😀

So I should also point out that cyder and syder did often appear in previous centuries, just not as frequently as sider or cider, for example. So it was always there, I’m just unsure if there was a specific trigger that increased usage in that period. I had wondered if wars with France might have made them want to create some distance from the French ‘cidre’, just because of national chauvenism, but that’s maybe just my pet theory (though somewhat reinfoced by the comments of the chair of the Royal Society in the late 19th Cdentury, which I found very entertaining).

Would love if someone could figure out a pattern. Maybe something for me to look at in the winter months. 🙂

LikeLike

Thanks for this diligent piece Barry, much appreciated and very useful as we try to resist misinformation. Sam

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Sam!

LikeLike

What a great article!

French’s book has been on my shelf for a while but I only got around to skimming some of the pertinent sections when prompted by this.

It’s frustrating because French includes enough accurate information in “The History and Virtues of Cyder” to disprove his own assertion. If the book had presented “cyder” and “cider” as retrospective terms to describe varying standards, uses and perceptions of cider…I think that would have been more interesting and less confusing.

Your Ngram chart clearly demonstrates that contrary to French “cyder” was not relatively popular in the 17th century. Nor were “cyder” and “cider” coincidental in common texts, being used to distinguish between two types of beverage. An interesting addition to your chart might have been some “control” words unrelated to cider which demonstrate similar variances in spelling. Playing around on my end – “cyon” vs. “sion” vs. “scion” recapitulates well known variance in spelling in the early modern period. “Cypher” vs. “cipher” shows an almost identical boom for the former spelling between 1730-1820.

Reading French generously, I think this was a mis-executed attempt at cultural preservation and development. I quibble with sorting the artform into only two distinct types…but I understand the work the author was trying to accomplish at a time when British cider was at a relative low point. Maybe the author was initially exposed to some 17-18th century texts which used the term “cyder” and developed a loose impression that terminology co-varied with cultural standards/expectations across the centuries of British cidermaking.

Looking at the state of our culture now – Awareness of cider is at a high, and we have no need to compromise our awareness of history in order to make grand simplifications which happen to enhance the salience of cider.

“Cyder” is dead. But it was a nice try. I think the best of French’s intentions are actually coming to pass.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, Adam, and what a great comment!

I wish I had thought of usuing some control words, as that would have made it quite obvious that the cyder spelling was of its time, and nothing more. Excellent idea. Your science background is showing!

Your interpretation of what French intended versus what he delivered is fair. I do believe it was well intentioned, but I have to admit, the first part is so heavy and fast with the “facts”, it leaves no room for careful consideration. He rather bulldozed through it, forcing a belief. I feel that left his intention more contentious that it could have been and, sadly, it has been repeated as fact so many times at this stage, it will be hard to dispell. I hope my small effort helps.

As a community, yes, cider is most definitely in a different place today, and it’s really exciting to be part of that. I think Roger would approve of the cider revival, regardless of how it was spelled.

LikeLike