With the exception of Basque & Asturian ciders, the words vinegary or acetic, are mainly used as pejoratives in relation to cider & perry. We talk about acidity more broadly across a range of drinks, acid plays an essential role in giving these drinks character, dimension and balance. When it comes to food though it seems more common to talk about acidity with some sort of prefix, it’s usually ‘slightly’ acidic or ‘overly’ acidic. We don’t often think of acid’s role in food unless it sticks out too much, daring to make itself noticed. But after salt, acid is the biggest influence of seasoning on your food (I need to point out before anybody says anything, that pepper is a spice, not a seasoning. It changes the flavour of a dish it doesn’t elevate flavour like salt or acid can. This is the hill I’ll die on). You’ll unlikely ever hear someone saying the balance of acid in their food was perfect. They’ll talk about a dish being perfectly seasoned, but the notion of acid playing a role in that is likely subconscious at best. All of this to say, it’s strange how we think of and approach the role of acidity differently in the world of drinks to the world of food, though they inherently go hand in hand with one another. Vinegar though is the one thing that connects both worlds like nothing else.

It’s maybe unsurprising to learn that my interest in vinegar is rooted in being a chef for most of my career. The importance of vinegar and the use of acid in food first becoming clear to me after reading Thomas Keller’s The French Laundry cookbook. A book that to this day is probably one of the best and most important books you can read as a young chef. Keller, the legendary American chef of the 3 Michelin star The French Laundry, generally considered to be at the time and even now one of, if not the best restaurants in America described using a few drops of vinegar to finish and add brightness to meat-based sauces, cutting through the richness and adding extra dimension. This was somewhat of a revelation to me, up until then vinegar was something you made salad dressing from or used to pickle things with, not used with the same nuance that it was here. It changed the way I thought about acid in everything. The importance of the right level and right kind of acid in a dish is same as the right sharp or bitter-sharp apple in a cider blend.

Over the past few years, the access to and availability of a range of different types and styles of vinegar have grown exponentially. The global vinegar market going from just over 6.98 billion dollars in 2023 to 7.28 billion dollars in 2024, with projections increasing year on year going forward. In short, vinegar’s popularity across the board is growing. What’s especially interesting is the growth in popularity of unpasteurised vinegars, with most major producers now offering an unpasteurised alternative in their range, seemingly fuelled in part by questionable positive health benefits that unpasteurised vinegars are thought to offer. As I’m no scientist or nutritionist I’m not going to spend any time lingering on the health benefits as it’s quite a contentious subject. My only take on it is while it certainly won’t do you any harm drinking unpasteurised vinegar, it’s up in the air as to exactly how much ‘good’ it will do you. The main interest for me when it comes to unpasteurised vinegar like unpasteurised anything is flavour. If like me you like eating unpasteurised milk cheeses, you’ll know the depth of flavour compared to a pasteurised counterpart is worlds apart. And as with all artisanal endeavours like cheese, wine & cured meats it goes without saying that the more natural the process, the more flavourful the end result.

So…cider? I hear you ask. Well, cider vinegar is one of the most popular vinegars on the aforementioned new vanguard of vinegars, with sales growing around 5.6% each year. And with producers such as Heck’s, Wilding and Oliver’s already offering cider (and perry in the case of Heck’s) vinegars, with Little Pomona soon to debut their offerings, it seems like a good time to explore small producer vinegar. Like their ciders, far away from the mass-produced mainstream vinegar in terms of flavour but also like their ciders an adherence to traditional methods that sometimes take years (as opposed to weeks in mass production) to reap results.

It’s a short break in the morning prepping a pastry section when I manage to find a quiet ten minutes in Tom Oliver’s busy schedule, not long after the year’s harvest has finished to chat with him about all things acetic. He tells me, half-jokingly, that he’s been making vinegar for as long as he’s been making cider in response to my arbitrary question of how long he’s been producing vinegar for. While it’s a humorous and quite tacit acknowledgment that success and failure often go hand in hand, it’s also the perfect encapsulation of civilisation’s long relationship with alcohol and vinegar. The two things essentially discovered together by our ancestors. The Babylonians in one of the earliest known examples were producing vinegars from fruit wines and beer from around as early as 4000 BC to use as a pickling medium for vegetables and meat. Even 6000+ years ago the relationship of vinegar and food seemed inextricably linked.

The Roman cookbook Apicius, thought to be from towards the end of the Roman Empire around the fifth century CE, but depending on accounts could be from as early as the first century CE, talks of vinegar being mixed with honey as a beverage, elsewhere there is mention of a simple vinegar and water-based drink called Posca. The bible mentions that vinegar was offered to Christ at the crucifixion. And bowls of vinegar know as Acetabulum were always present on the tables of Roman banquets to dip bread into this starting centuries long terrible trend of dipping bread into oil and vinegar. The Latin language also being the etymology of the word vinegar. Vinum acer meaning sour wine, later evolving to becoming Vin aigre in French. Perhaps unsurprisingly given the French’s relationship to wine making, it was they that first refined the vinegar making process during the Middle Ages. The city of Orléans in the Loire valley after which the oldest process of vinegar making is named (the process is also known as the surface process) would utilise spoilt barrels of Bordeaux and Burgundy on their way to Paris. For thousands of years the process was a simple but unpredictable method of half filling containers with wine or other such alcoholic liquids and letting them sour. This could take anywhere from weeks to months. The Orléanais would half fill wine barrels with wine diluted with water, the porous nature of the wood along with only filling half-way maximising the wines surface area to oxygen thus expediting and help standardise the process. Once fully acidified the majority of the barrel was racked off and fresh wine added into the barrel to start the process again.

It’s at this point I should probably cut straight to the cold hard science that I know you’re craving. At its core, acetic fermentation requires three things oxygen, ethyl alcohol & acetic bacteria, specifically Acetobacter or Gluconobacter. These bacteria live on the surface of the fermenting liquid and metabolise the alcohol (C₂H₆O) into two constituent parts, acetic acid (CH₃COOH) and water (H₂O). Hence greater surface area exposed to oxygen the quicker the process. Conversely if the process goes on too long the acetobacteria can start to metabolise the acetic acid creating more water and carbon dioxide which weaken the resulting vinegar. During the metabolism the bacteria combined with other microbes create a form of cellulose on the surface that’s typically known as a ‘mother’ that covers the entire surface. If you’re au fait with kombucha making this is similar to the slightly more technical acronym of a SCOBY (symbiotic culture of bacteria & yeasts). These are beneficial for the fermentation but also have to be periodically removed as they continue to grow layer upon layer taking up space in the container if left unattended. These ‘mothers’ as the name suggests can then be used to inoculate new batches of vinegar with acetic bacteria, again speeding up the process. Because of the voracious nature of the acetic bacteria the vinegar making will always be done as far away from alcohol production as possible to avoid the risk of the bacteria making its way into something destined to be drunk.

When I asked CR co-editor Barry Masterson a few questions as I started to think about this piece his first response was ‘well vinegar is what all cider wants to be really’. As it turns out cider & perry might just be the perfect mediums for vinegar making. In general vinegars tend to be 5%-7% acetic acid. At this level there’s enough acid present to stop any other bacteria taking over that might cause spoilage. This is especially important if they remain unpasteurised. There are a few exceptions to a high level of acidity like some Japanese rice based vinegars at around 4% acetic acid and Chinkiang black vinegar from China which can be as low as 2%. Abv is the key factor to the final acid content, an abv of 6-8% will produce a vinegar with the desired acetic acid content of around 5%. The higher the abv though the more it inhibits the acetic fermentation. Anything from 10-12% abv onwards tends to give the acetic fermentation a hard time, which is why the Orléanais would dilute the wines before starting the vinegar making process. Serendipitously, full juice cider & perry exists (mostly) in that perfect little abv sweet spot. Cider & perry like wine also has the bonus of malolactic fermentation alongside the eventual acetic fermentation. The fermentation of the malic acid helping to soften tannins and some of the acidity as well as augmenting the aroma leading to a more rounded finished vinegar. Just as with cider, the perception of the acid comes down the structure, body and fruitiness of the vinegar.

In cider the perception of acetic acid is referred to as VA or volatile acidity, this becomes noticeable at around 75ppm which equates to roughly 0.07g/l. In relation, the more acetic leaning ciders of Spain and the Basque region fall around the 2g/l mark. The Asturias protected designation of origin (PDO) sets the upper level of VA for their ciders at 2g/l, the Basque PDO at 2.2g/l incidentally the maximum allowed for cider under Spanish law. This isn’t to say all Asturian & Basque ciders have these levels of VA as the trend is moving towards lower acetic levels. With the natural ciders, as they’re not filtered, pasteurised or force carbonated, it’s desirable to bottle them with a lower VA around 1.5-1.7g/l as the acidity can increase with time in bottle. Within the Basque PDO there is also a category for Gazi-Gozoa cider, mainly produced in the Northern Basque region, the three provinces of Labourd, Lower Navarre & Soule in France. The VA levels being set at 1.22g/l, the maximum under French law for something to be classified as cidre. To put that in context vinegar can have a level of VA anywhere between 30g-90g/l.

The commercial or rather industrial process of vinegar making, as you might expect, tends to favour expediency. The submerged culture method (also known as the acetator process) relies on continuously pumping air into tanks of alcohol that have been inoculated with acetic bacteria, maximising the surface area of the liquid exponentially and warming to a temperature for the acetobacterium to thrive, cutting the fermentation time to a matter of days. As a result, a lot of these vinegars lack the nuances that come with a long slow fermentation. The one point about this method that is worth mentioning is its adaptability for home vinegar making, should you be so inclined. Restaurant Noma in Copenhagen has been on the forefront of high-end cuisine for the last two decades and has been voted the world’s best restaurant no less than four times, most recently in 2021. It is among many things a Mecca of all types of fermentation. When their book, The Noma Guide to Fermentation, was released in 2018 it became (along with Sandor Ellix Katz’s The Art of Fermentation) the go-to book for chefs looking to unlock the mysteries of misos, garums and other such sources of flavour. On the vinegar front they adapted the submerged culture method to create a unique range of vinegars quickly and consistently to fit the demands of a constantly busy restaurant environment. By using the air pump from an aquarium fed into a container of alcohol back-slopped with a previous batch of vinegar, they could replicate the method on a smaller scale within a few weeks. Should you want to get serious about a little homemaking vinegar project, then this is probably the fastest way to go about it. As vinegar once fully fermented won’t get any sourer and is stable long term there is the potential to then barrel it for a period of time to soften and get some of the nuance missing from the quick initial production.

It became obvious after talking to a few producers that everyone was using some variation of the Orléans method for their production. I get it, it’s traditional, it’s relatively hands off to do and there’s something beautiful about it happening in sync with and along a similar timeline as the cider making. But I discovered there’s more than just the traditional versus the industrial. Mixing business and pleasure by chatting to Sam Leech of Wilding whilst picking up their new releases during their last, pre-Christmas farm open day of the year, he referenced a technique that I hadn’t yet come across from a book that I couldn’t imagine not being on Sam & Beccy’s book shelf. The Complete Book of Self-Sufficiency by John Seymour talks about what I’d later find out to be the trickling process, or generator process. Alcohol is continuously poured through a vessel containing beds of wood chipping or shavings inoculated with acetic bacteria. The technique began life in France around the 17th century where grapevine twigs were used for the beds that the wine was poured over. In the 18th century, Dutch scientist Hermann Boerhaave, who was one of the first scientists to study vinegar and first realise the importance of both the mother and oxygen to the vinegar making process, introduced the continuous trickle over method. This method was then industrialised in the Grand Duchy of Baden, now part of modern Germany, by Karl Sebastian Schüzenbach in 1823.

From 1823 onwards this remained the industrial method of production, until the end of World War II. During the war the demand for antibiotics were understandably high, the greatest demand was for penicillin which between 1943-45 went up in demand 25-fold. Penicillin was hard to scale up due to a method of manufacture not dissimilar in approach to the Orléans method, where the bacteria was grown on the surface of a nutrient rich medium in a flask. Scientists from pharmaceutical companies Merck and Pfizer, along with support the US government, found a way to produce penicillin by growing it in a liquid directly injected with a constant stream of oxygen cutting down the production time needed. Post war this method got reverse engineered for vinegar into the submerged culture method, at which point it became the industry standard for production.

After initially coming to this in a culinary frame of mind I soon realised that vinegar making was another albeit tangential insight into different cider makers individual methodologies, another glimpse into their process. Most surprising was discovering Tom Oliver, a man renowned for his blending, doesn’t undertake any post acetic fermentation blending. After selecting the cider batches destined for vinegar they simply go into IBC’s or barrel and ferment into vinegar there, maturing for around two years before bottling. Meaning each batch is a unique expression of time and place. Wilding’s approach is to ferment and mature in a selection of ex-wine and spirit casks for a year before blending creating much more of an overall style. Heck’s perry vinegar, which I’m more than a little evangelical about, is an incredible ten year old batch, and whilst it won’t receive the same adulation as Kevin Minchew’s 23 year old Last Hurrah perry (from last year, it should be held in equally high regard as another example of what the combination of the perry pear and time can achieve together.

Whilst I found that most makers started their processes by choosing ciders that they felt would make good vinegars, James Forbes of Little Pomona has gone one step further, selecting the apple varieties he feels will make good vinegars. Some of the results of which are upcoming single variety vinegars, a Yarlington Mill and a smaller batch of Dabinett respectively. To my mind this could be a fascinating new prism through which to view the characteristics of different varietals. As well as the culinary opportunities it presents, tailoring vinegars specific dishes or preparations whilst knowing the variety and terroir is incredibly exciting. Also given the availability of some beautiful solera method wine based vinegars on the market and Little Pomona’s success with their three solera method cider releases so far, I’ve got my fingers crossed this might be something James will explore for aging vinegar.

Beyond the slightly esoteric, another reason to explore these fine cider vinegars is the rise in popularity of low and no alcohol drinks, something that has become a massive growth market. Between 2022-23 the low and no sector saw a 47% increase in sales, with an increase of 19% predicted in 2028, which would be around a £0.8bn industry in and of itself. The beer industry has always led the way with low or no alternatives, but now even a major spirit label has got in on the act offering a 0.0% alternative. Cider is now plowing a furrow here too. Normandy & Brittany based brand Galipette take a special mention personally for their very good non-alcoholic cider. But inevitably the non-alcoholic alternatives tend to be a bit one dimensional and for me personally far too sweet, both from a taste and a health perspective, to make them a regular alternative option. Price point is also a factor, low and no alternatives are priced in a similar bracket to their alcoholic counterparts compared to regular soft drinks. In cider vinegars you have nuanced characteristics of the cider and the apples, none (or extremely low amounts) of the alcohol, a desirable price point and a blank canvas in terms of flavour options. Sweeten it with sugar or honey, or don’t sweeten at all, top up with tonic water, sparkling water or tap, make it into a cordial or a shrub by adding fresh fruit and/or spices, the list goes on. The range of possibilities for a natural, non-alcoholic beverage is cider vinegar’s hidden weapon.

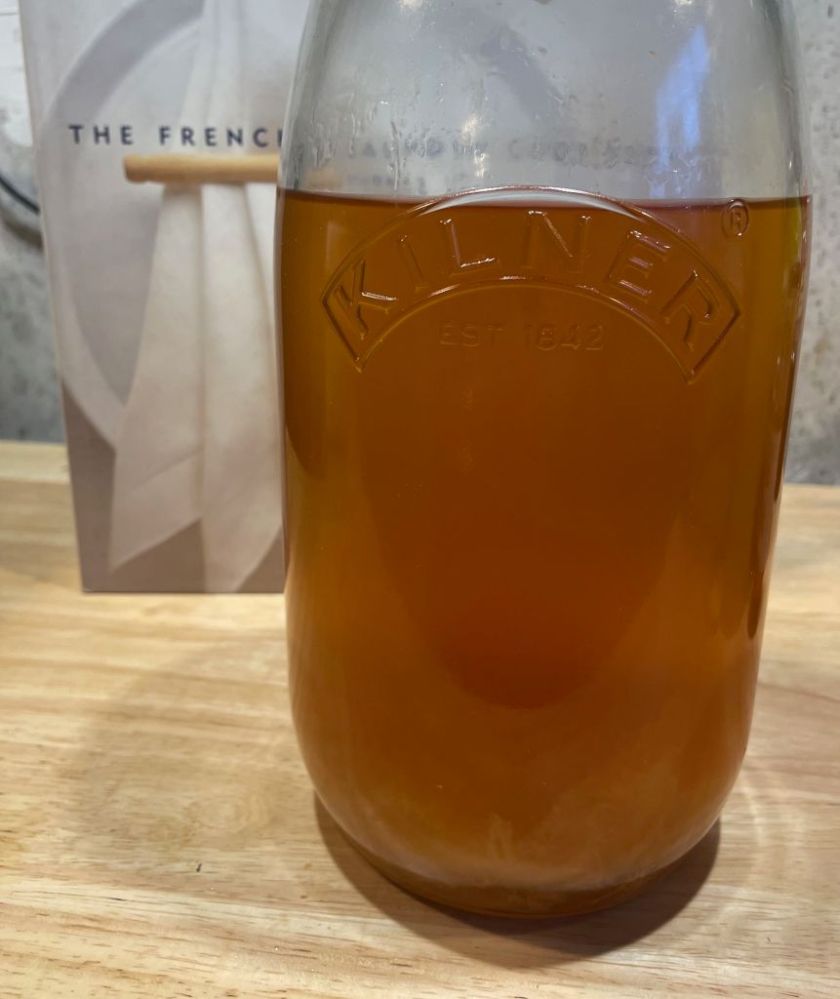

Unlike the many of my peers at Cider Review, though I’m not a cider maker, bar helping with an occasional days harvest here or bottling there, I haven’t dipped my toe into the world of making cider (…yet!?). But one thing I have been making, if only for my own enjoyment, and my own frugality is cider vinegar at home. Sometimes I’m left with the dregs of a bottle, normally high on sediment or occasionally a bottle of something that I haven’t enjoyed drinking, so it goes into the vinegar jar. This is unlikely to ever yield anything magnificent, but for everyday vinegar use it’s definitely better than something off the supermarket shelf. And as a chef it scratches the fermenting itch. You don’t know how important it is as a chef to be able to say we’re fermenting something! Anything!

So, should cider be allowed to get its way? Accept its fate and let it become vinegar? Well, of course not! But on the occasion that it does manage to get its own way, I think we should still have cause to celebrate the results. An under-appreciated gem from an under-appreciated gem, and when it comes to cherishing of all things, the sweet ain’t as sweet without the sour.

Cover image: the Little Pomona vinegar store. Photo by James Forbes.

Discover more from Cider Review

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Brilliant article Brett! I too am a fan of cider & perry vinegar. On food, but also, a tablespoon in a pint of water daily. I like the idea of mixing with soda water on dry days – will have to give that a go soon. So far I’ve tried Olivers, Whin Hill, Three Saints, and currently, Ross Cider. All tasty and different in their own ways.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cider Vinegar: A Cautionary Tale

About 15 years ago an old boy in Wragby, Lincolnshire, had a pickled onion shop – all he sold was pickled onions: In a dim room jars and jars of them lined the shelves and were stacked up on the counter, strong and potent, like drowned men’s eyes staring at you from the inky depths. I sometimes popped in on my way home from work. One day he had a batch of special onions pickled in cider vinegar for a 50p premium – fantastic! I slapped the required shekels on the counter for two humungus jars and drove home, salivating all the way. Now, eating proper pickled onions is either a team sport (if you are blessed with a significant other who shares one’s pickled proclivities) or a solitary pleasure with consequences (if, like me, you are not). Get home, whip up a huge doorstep of a cheddar sandwich and open the jar. Alas! Braving the miasma of rancid blue cheese and sweaty socks (should have stopped there, but I had already accepted my fate; the dog-bed beckoned and I was committed!), and in the intrepid spirit of gastro-exploration I bit into the pungent bulb – Oooff! The acid was right off the scale and was eye-wateringly sharp enough to burn through four steel decks of a starship before Sigourney Weaver could climb into an escape pod. I was lucky to avoid hospitalisation and ended up on the sofa that night, as even the dogs wouldn’t let me in……

LikeLiked by 1 person