Last March I published a translation of a German article from 1867, extolling the virtues of Swabian cider and giving us an insight at how cider and perry was made and experienced at that time. An eye-witness account of the living culture of cider in that region 157 years ago. At the time I commented that I felt such peeks through the keyhole of time can give us an understanding of processes that have hardly changed over history, and indeed, I strongly feel that the tapestry of cider and perry culture that covers Europe is a shared one that continues to develop even further afield.

Which takes us to 1913 and something else I would like to share. An article in Die Woche by one Sigmund Feldmann on the topic of cider. Or rather Zider, a curious, and I would tend to say relatively rare, archaic German spelling of cider that had a small spike in usage in German literature at the end of the 18th Century, and very brief “resurgence” in the early 20th. Although in this article it seems he may be mostly writing about the French tradition, some of the processes involved, like adding pears to the mix, feel distinctly southern German.

Die Woche was an illustrated magazine published from Berlin from 1899 to 1944. When it began, it was a time when printing technology was developed enough to allowed for a cheap, mass-produced and up-to-date, newspaper that had a focus on images closely linked to the articles. I suppose a kind of early tabloid, but while the magazine covered entertainment, serial novels and gossip, it also covered more demanding topics of the time. Well, like cider!

Feldmann appears to have been a regular contributor to Die Woche, writing on topics as diverse as from “The Natural History of the Monocle” to Indian clay figurines. Indeed, he also occasionally contributed to Die Gartenlaube, the magazine from which my previous cider-related 1867 translation was taken. From the article below, he seems to have been very much a fan of cider, and takes no prisoners on his opinion that it is very much deserving of respect, and should belong in the rotation of any compound drinker, as our friend Rachel Hendry would put it. Indeed, I think Rachel would approve of what Feldmann says of the people of Württemberg and their love of wine, cider and beer in equal proportion.

I hope this translated article entertains you as much as it did me, showing as it does that the perception of cider in some quarters has changed little in the 111 years since it was written, but we still fight the good fight.

* * *

Der Zider

Siegmund Feldmann

Zider may sound more refined, but it is nothing more than Apfelwein. The gentleman who is studying the feudal wine list, peppered with castle prints, in a ‘dead posh’ restaurant under the waiting eyes of the heavenly coiffed waiter may shrug his shoulders at this word. ‘Eww, Aeppelwine!’ Easy, dear sir, easy, Aeppelwein, to use your parodic Sachsenhausen dialect, is a very good and wholesome thing, provided it is prepared with devotion, understanding and a clear conscience. Those who don’t like it should, in God’s name, drink something else, although the one does not exclude the other. This is demonstrated by the people of Württemberg, who are the biggest consumers of cider in the German Empire and would not miss it for anything in the world, without spurning a fresh glass of beer, on the contrary. And the people in the Taunus and other areas around Frankfurt have the same attitude.

Of course, these are not the real Zider drinkers. They would die of thirst between a bottle of sparkling wine and a litre of Urquell if they didn’t get their cider. These fanatics can only be found in France, in Picardy, Brittany and Normandy, whose populations, high and low, large and – unfortunately! – and small, have chosen the cider as their daily drink. It is as essential to the livelihood of the entire north-west of France as bread and is therefore one of its greatest and most productive agricultural riches. Every year, fifteen million hectolitres of cider are pressed in France, which yields 225 million at an average price of 15 francs [per hectolitre]. And this only includes a small part of what the farmer who produces it himself consumes for his own well-being. Profit!

After all, it is curious that France, which is almost drowning in the abundance of its grape juice and has sometimes had to let it spill sinfully onto the streets to no one’s delight simply because there were not enough barrels to fill with this blessing, is also at the forefront in the preparation of cider and produces more of it than all other countries put together. This leads to the conclusion that cider is not an emergency product, not a surrogate for ‘real’ wine, but an autocratic drink in its own right, and experience confirms this conclusion. In bad, expensive wine years, cider must of course help to cover the shortfall, because statistics have no influence on our thirst; but on the other hand, the same statistics teach us that hardly any less cider is consumed in the fat wine years than in the lean ones, although it costs almost as much as the so-called noble grape blood, which all lyricists with and without a golden edge sing about with gusto. Incidentally, the cider is also sung about. Perhaps with less gold trim, but probably with more conviction. You can hear a lot of songs about the price of this drop in Norman pubs. The pretty chorus: ‘Vive le cidre de la Normandie! ‘ from the famous operetta ‘The Bells of Corneville’ is just an echo of this. So the cider is not an improvised product and not an imitation. That’s what the gentleman in the fancy restaurant with the heavenly coiffed waiter who thinks so little of ‘Aeppelwein’ should be told.

He would never have come to this absurd conclusion if, like any decent person, he had carefully read the seventeen volumes of Strabo’s Geography, in which it is reported that the Gauls were excellent at making various drinks from apples and pears. At that time, two thousand years ago, there were certainly no vines and no phylloxera in Gaul, but the cider was already flowing in streams across its fields, so it was there even earlier. Strabo is an unsuspicious source and just as reliable as the Basques, who boast of being the inventors of the cider. This is at least possible, as they were in the country before the Gauls, so there is no chronological objection to their claim. However, this industrious people exploit the fog that surrounds their origins a little too deliberately by ascribing all sorts of merits and events to themselves, the accuracy of which even the greatest privy councillor cannot verify. They swear, for example, that Basque was the language of paradise and that Eve only succumbed to the temptations of the serpent because it breathed Basque sounds into her blushing ear. If this is true, then the whole story can of course be explained very easily. According to the most credible tradition, Eve only ate a single apple. But since there were still a lot left, she would certainly have made cider out of them so that nothing would perish. And since she was a Basque, the cider would indeed have been a Basque invention.

The fatheads in the north-west don’t have the agile imagination of their compatriots who have been clinging to the slopes of the Pyrenees since time immemorial and don’t give a damn who invented the cider. If only they get enough of it! And if only it turns out well! In these two eternal questions their love for the clod trembles, and just as the German farmer walks through the fields to see how his and his neighbours’ crops are coming up, so his Breton and Norman brother stares searchingly into the branches of the apple and pear trees on which his hope is swinging. And in the evening, in the parlour with the large clock case and the strange beds that rise up above the chest of drawers, this provides an endless source of conversation deep into the winter. Because what wants to become a righteous cider can only be pressed from late fruit that has been stored in the meadow for a few weeks, where it has to be looked after like a sick child so that it doesn’t freeze or wither. These are worries of which the gentleman in the fancy restaurant has no idea; just as the preparation of the cider in general is associated with intricacies and subtleties that would astonish the cultured person with nail care, unless he had first studied the profound work ‘De Pomaceo’, in which Julien le Paulmier, personal physician to Charles IX and rector of the University of Caen, expounds on this important subject in Latin in 1588.

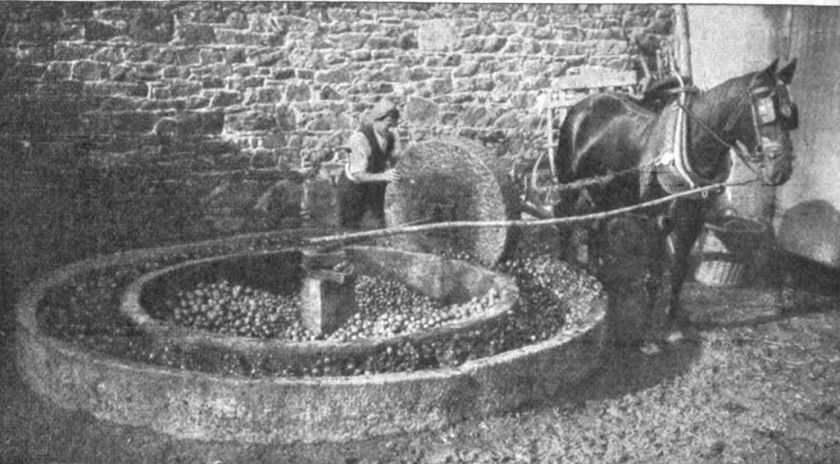

The technical process is very simple. The apples and the addition of pears, which is hardly avoidable to increase the sugar content, are poured into a large round trough with a concentric trough running around it and doused with water to soften them. Such a trough is as much a part of the home as the fireplace and the washroom, it is as much a part of the house as the window and door, and it can even be found in the yards of modest farms that have no fruit of their own. Because even these ‘disinherited’ people do not buy the indispensable cider ready-made; that would be against all sacred tradition.

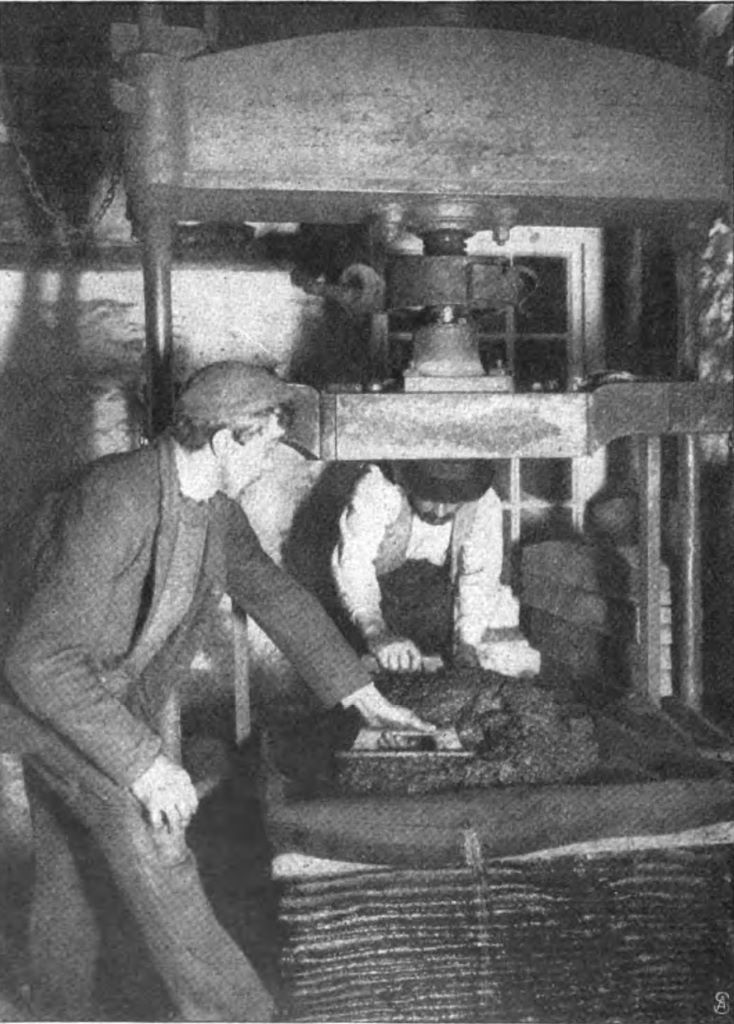

They simply buy the apples and then call in one of the itinerant ‘cidriers’ who, with their little cart and the millstone packed on it, form an original staffage of the Norman nests in winter. The cidrier, who is paid either by the hour or by the quantity processed, squeezes the fruit into pulp with the help of his cart and then returns a few days later with his hand press to finish the now fermented pulp. However, this is the most primitive form of preparation, which is outdated in places where the community has set up a workshop or associations have come together to purchase a more solid press. And these workshops eventually lead to the factory, where cider is produced for wholesale and export with an even greater degree of ‘progress’. However, this is by far the smaller half of the total production.

Whether made at home or in the factories, technology is secondary and the main thing is experience. It’s not the machines that matter, nor the chemists’ retorts that painstakingly work out how many glycoses, tannins, phosphates, albuminoids and other mysterious substances are in the cider, but the touch and the eye, that old wisdom of heredity that has become a feeling, that instinctively makes the mixtures, knows the characteristics of each type of fruit, guesses the moods of the moût or mash, respects the rights of the jus or juice and is not mistaken about the course of fermentation and clarification for even a quarter of an hour. Only where this wisdom prevails is that cider created which, in its good brands, provides a pleasant drink for even the most discerning palates and tastes more delicious than the finest vintages of Burgundy and Bordeaux with certain Normandy-Flemish dishes, the Petit Salé, for example, or even the adorable Tripes à la Mode de Caen.

Once again, the gentleman in the fancy restaurant won’t believe me. Well, then he can order a bottle of champagne or Steinberger Kabinett from his heavenly coiffed waiter for all I care. But he shouldn’t disgust other people with his stupid remarks.

* * *

References

Feldmann, Siegmund (1913). ‘Der Zider‘ in Die Woche, Band 4 (heft 40-52). Germany: A. Scherl. pp 1838-1841.

Discover more from Cider Review

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.