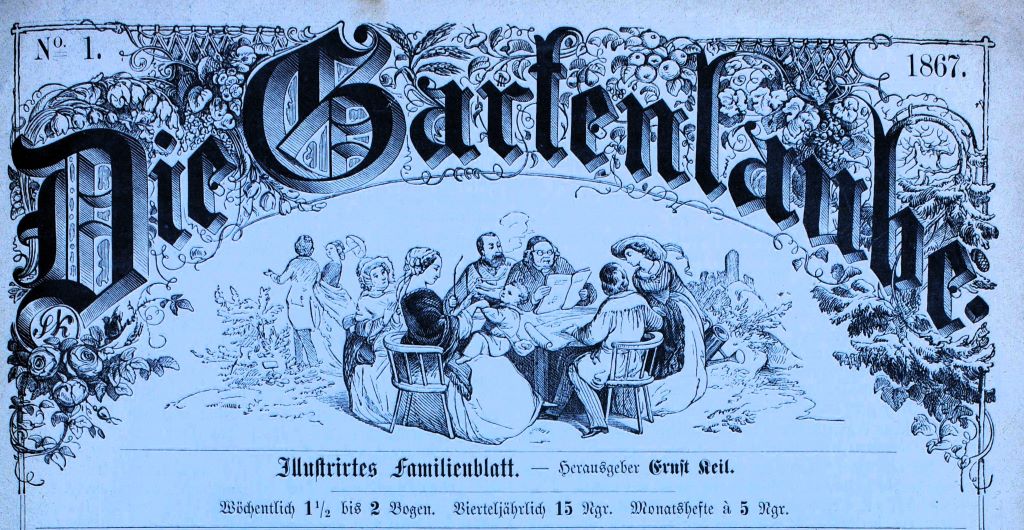

Die Gartenlaube – Illustriertes Familienblatt (The Garden Arbour – Illustrated Family Journal), published weekly between 1853 to 1944, was a German magazine that was a forerunner of the concept of modern day magazine-style publication. Distributed throughout the German-speaking world, it contained a mix of content for the whole family, touching on short stories, poetry, natural science, current affairs and, as the title suggests, illustrations. Prominent writers such as Goethe and Schiller graced its pages.

I recently found an 1867 article penned by an author that simply went by “R.A.” that provided a wonderful description of cider making in Swabia, the region around Stuttgart down here in southern Germany. That region was, and I daresay still is, the second largest cider producing region of Germany.

While normally I bookmark such things and pull out specific parts that tickle my fancy for later use, I think this particular article is worth sharing in its entirety for its wonderful writing and a lovely insight on the processes used in that region at that time. It’s curious how, in some ways, little has changed, including some of the opinions of the author’s companion (I especially like his comment on dilution), but I will simply leave the translation for you to hopefully enjoy as much as I did.

* * *

It was a clear autumn afternoon when I walked towards the Bopserwalde, high above Stuttgart, in the company of a Swabian friend, in order to make an excursion from there to the Meiereien von Hohenheim, the real children of the heart of the late King Wilhelm.

We walked past fruit trees and vineyards, and so the conversation naturally turned to fruit growing and viticulture. As a North German, I was quite unfamiliar with the nature and operation of the latter, and so I was happy to be instructed by my knowledgeable companion.

“You must be literally drowning in wine,” I said to my friend, pointing to the vineyards rising up all around Stuttgart. “The wine is growing into your window, so to speak!”

“There’s no danger with the former,” replied my companion. “However, we can see the vineyards rising at every end of the road, but they also make sure that we don’t drink too much, or even, as you said earlier, drown in wine. Although the wine grows in the immediate vicinity, almost in the city, it is not as cheap as you might think. That’s because of the many exports. How many a Swabian wine is labelled and drunk outside as this or that ‘Château’!”

“If wine is relatively expensive for you, what do your workers drink while they’re working?” I asked.

“Moscht!” (i.e. apple and pear wine) he replied in good Swabian. [Elsewhere simply pronounced Most, but the Swabian and Badish dialects make the S a shhh sound, like you’re in the wesht of Ireland]

I tightened my lips at the word “Most” so that I wouldn’t miss a drop. A number of years ago in Berlin, a fellow student had taken me to the ‘Apfelpetsch’ garden, and I still remember the vinegar flavour with which I was led and which I couldn’t get out of my mouth for a long time.

“Yes, a good glass of Moscht is a real delicacy!” my companion continued.

“For lovers of it!” I replied. “For my part, I can’t make friends with cider and prefer water.”

“Yes, of course, it depends on what it is and,” he added after a pause, “how it is prepared. We should drink a bottle of last year’s ‘Bratbieremoscht‘ in the ‘Löwen’ in Degerloch today, and I’m convinced you’ll get a better opinion of our ‘Moscht‘ then.”

“What – Bratenmost – or what did you call the crop?”

“Koi G’wächs!” he laughed. “It’s called Brat-Birnen-Most in High German.”

I asked him to tell me something about it and about fruit wine making in general, and he gladly agreed.

“We made our own cider yesterday,” he said. “It’s a pity you didn’t arrive earlier, you could have seen the mashing for yourself.”

He then told me the following:

“Here in Swabia, cider is quite an important article of commerce; but it also serves the labouring peasant, as well as workers of the lower classes in general, as a very healthy drink, which at the same time provides the most useful refreshment and tonic, provided that the cider is well prepared. In many families, it is actually the household drink, which, when consumed with half a pound of bread, is more satisfying than a pound of bread without cider. We can therefore justifiably claim that a rich fruit yield saves a lot of bread. As far as fruit wine in particular is concerned, apple cider is generally preferable to perry because the former is better, more flavoursome and has a longer shelf life. While apple cider from good varieties will keep for three to six years, good perry will only keep for one to three years.

“Among the apples, the so-called ‘Luiken’ (a red striped variety) is the most popular for making a good cider, along with many other varieties, and among the pears the German or Champagne Pear [Champanger Bratbirne] and the Wolfsbirne. The sugar content is decisive in the selection of fruit suitable for cider, as the quality and shelf life of the fruit cider wine depend on its richness. Above all, it is important that late autumn and winter fruit with a tartaric [vinous acidity] taste is stored in dry places after harvesting, covered with a cloth or sacks, so that it reaches ‘storage ripeness’, which is indicated by the change in colour of the fruit. Furthermore, mixing the fruit with tart apples or rough pears is recommended for all varieties that have a sweet or tart flavour or are soft and pasty, as the must of the latter otherwise easily becomes heavy, viscous or tough.

Once the fruit has been broken and has reached the necessary ripeness, it is poured into the stone grinding trough or, as they say in the country, ‘Werkeltrog’. In this trough, the fruit is crushed (as shown in our illustration) by a grinding stone, through which a rod, often twenty feet long, passes, by means of which the stone is set in motion by pushing and shoving farmhands and maidservants. After the stone has been moved back and forth a few times in the arched grinding trough, the fruit that has been pushed to one side is scooped into the centre, then squeezed again and the process continues until the fruit is finely ‘mashed’. This fruit pulp is called ‘troß’. Nowadays, squeezing in grinding troughs is only used for small quantities of fruit, as fruit mills are used for large quantities. The view that water should be added when preparing fruit must is often expressed, especially by the majority of cider makers. ‘This makes the must better and more durable, whereas without the addition of water it would become too viscous and thick,’ they explain. With early fruit and sweet fruit varieties, the addition of water may be excusable if one does not have any tartaric, rough varieties for mixing in order to increase the shelf life. Otherwise, however, the view is quite wrong, and its realisation is nothing more than a process of multiplication at the expense of the quality of the drink.

The ‘worked’ fruit, the ‘Troß’, is now scooped out of the grinding trough using ‘Gölten’ (a kind of shallow bucket) and taken to the press (which we can see to the left of the observer under the small canopy in our illustration). In other regions, however, such as on the Main, in France, especially in Normandy, a different procedure is used beforehand, which is said to be preferable to ours. There, the ‘Troß’ is not taken to the press immediately after crushing, but is left to stand in vats for five to six days at a warm temperature, or ten to twelve days at a cold temperature, where it undergoes the first stormy fermentation; this process is called ‘Aufnehmenlassen’ (leaving to absorb) [maceration to you or I]. The well-known Frankfurt ‘Aeppelwein’ is also treated by means of ‘Aufnehmenlassen’, but the must is only exposed to the stormy fermentation for one to two days. After the must has reached the necessary degree of absorption, it is drained and the coarse, remaining parts are put under the press, which then yield a smaller must. The best known presses are the tree or lever presses and the screw presses, of which the iron presses are preferable to the wooden ones because of their considerable pressure. In areas where wood is scarce, the remaining pomace is dried and utilised as fuel, thus providing a not insignificant benefit.

When the must is filled into barrels, the latter must be perfectly good, clean and free of mould. Depending on the treatment, either bottom or top fermentation takes place in the cellar. In the former, the cask is not completely filled, the bung is only lightly placed on top and only topped up once the alcoholic fermentation is complete, a process which makes the must richer in content. In top fermentation, on the other hand, the barrel is filled to the bung and the bunghole is left open, from which the moving liquid ejects the gross lees and impurities during fermentation. The must can be drunk as it comes out of the press. It then has a cloudy, brown appearance and tastes pleasantly sweet. After it has fermented in the barrel for about eight days, it is ‘räs’ (a bitter-sour flavour), where it tastes best to many cider drinkers, but makes others who are not used to the taste tighten their lips.”

“‘S isch eppes Gut’s, so e räser Moscht,” [fun dialect, “it’s something good, such a bitter-sour cider”] my friend concluded his thorough instruction and clicked his tongue in anticipation of future cider delights.

An avenue of fruit trees stretched out in front of Degerloch, with neat orchards on both sides of it on a green plain. “For years,” my companion began again, “we haven’t seen such an abundance of fruit on our trees.” And indeed, it was a marvellous sight! Nature had given here as if with full hands. The abundant blessing of the year pressed the branches down to the ground and everywhere you could see supports placed to lighten the heavy load on the branches so that they would not collapse underneath.

The red roofs of Degerloch, a church village high up on the hill, which is a favourite place of the people of Stuttgart, emerged from the orchard. Everywhere one could see maids with fruit baskets under the trees, which were being shaken and thus freed from the heavy load. In front of one of the houses they were making most – it was exactly the scene that the artist has captured in the accompanying picture. Noise, singing, shouting and laughter could be heard. And yet you could see from the taut, strained movements of the labourers that mashing was no easy task. It seemed as if they were all working for pleasure and that mashing was one of their favourite pastimes. The maids walked up and down with the fruit and dragged it to the “work trough”, in front of which the farmhands moved the millstone with the old farmer, laughing and joking. Two maidservants were posted at either end of the grinding trough to shovel together the “Werkelt“, which a farm labourer later had to press out. His work was not easy either, indeed it was probably the hardest. Nevertheless, he sang: “Do!” and while he pulled the swing of the press with all his strength, he paused for a very long time. Then, as he whirled the spindle, he continued to sing: “Look at my heart-thousandth treasure” and looked over at the pretty young maid who was working at the work trough in front. The other servants had heard the long drawn-out “Do” and the following “Schatz” [treasure: Schatz is still a common term of endearment in Germany] and interrupted the singer with loud laughter and coarse jokes.

As we emptied the bottle of last year’s Bratbirne perry in the Löwen Inn, which tasted like champagne with a lively mousse and excellent flavour, I reconciled myself to the perry. The innkeeper told us how the carefully selected green Bratbirne, which in and of themselves had a rough flavour, were collected in piles three to four feet high to ripen for storage, crushed after turning yellow and soft, and then the must had to undergo the stormy fermentation in “Kufen“ [vats] with the pomace. After draining [off the pomace], it would be poured into barrels and from these into bottles, the cork of which would be tied with wire. The bottles had to be laid down so that the cork always remained moist.

When I asked the innkeeper whether other cider stays in the barrels for a long time, he replied: “Rarely, because the Swabians usually drink their cider early.”

Translated from: R.A., (1867). Bei der Mosterei in Schwaben. In Die Gartenlaube, Heft 42, S. 667–670. Leipzig: Verlag von Ernst Keil.

Discover more from Cider Review

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

How delightful, Barry! Thanks for sharing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading, Beatrix! 🙂

LikeLike

Great article about Moscht of which I have drunk many a Halbe over the last 45 years.

Good stuff can be found at Walter Held’s, Sonne, Pappelau in the heart of Schwabia.

I hope to try some of yours some time this year when I’m over….Andrew, Brecon Beacons Cider

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you enjoyed it too Andrew! And looking forward to seeing you in Nord-Baden 😀

LikeLike

So they did make perry in Swabia back in the day. Not that long ago either, in the grand scheme. I wonder how that tradition got lost.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! But no idea at what scale. I think Geiger has mentioned some source that goes back a little earlier, I’ll have to find out. But it makes sense with all the pear trees around.

LikeLike

Pingback: The Great Big German Perry Tasting | Cider Review

Pingback: Notes from the past: Der Zider, 1913 | Cider Review

Thanks for sharing this, Barry! You might be interested to know that where I live in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, there is a massive Swabian population, whose ancestors primarily came from the villages around Stuttgart between 1829-1900. In my research into the history of local cider mills in the county, I found a large number of them(over 1/3) were owned by the Swabian immigrants or their descendants. Ann Arbor was one of the largest cider making areas of a large cider making state, and a big part of that was due to the Swabians and their love of cider. They also grew a lot of pears, and made pear cider/wine, which is think was another contribution from the Germans. If you want to learn more, my email is xxxxxxxx [removed by Ed.]

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment, Pat! It’s really fascinating how emigrants bring their traditions with them and enrich their new home. Of course as an immigrant myself, I may be saying that! 😀

I wonder, did they also bring scions and trees with them. I will send you an e-mail 🙂

LikeLike

Pingback: Pyrus Invictus – Barry’s CraftCon 2025 Keynote | Cider Review

Pingback: Jörg Geiger, the vanguard of non-alcoholic cider and perry | Cider Review

Pingback: A Schwäbischer Cider Tasting Box | Cider Review