An in-conversation between Tom Oliver and myself at the Museum of Cider, Hereford, for PerryFest 2025, the audio of which was recorded and transcribed for posterity here on Cider Review. When we announced this talk, there was a fair amount of online chatter about it being recorded for those that couldn’t make it due to distance to the venue or prior commitments. It was Tom’s birthday on this particular day, so we got the whole room to join together and wish him a very Happy Birthday before we began. Here’s to many more to come for one of the UK’s shining lights of cider and perry making!

CR: Can you imagine in wine or whisky terms if we ever got this close to losing an intrinsic part of the drinks category: if we lost Sauvignon Blanc or Pinot Noir grapes, or Laureate, Concerto or Optic barley? I don’t think we’d be allowed to get that close to losing an ingredient in those categories anymore, but in perry pear terms, I think we have come close. Thankfully, things have gone to the edge of existence and through the good work of people like yourself Tom, varieties have stepped back from the precipice.

Tom Oliver: I think it may be an interesting way of looking at Perry. The “threatened aspect” is quite often the key to getting things moving again. Certainly, within the interest that we’ve had from, say, slow food, going back 20 years, the key to it was the threat: the fact that there really is an ever-decreasing supply of the raw material. As those trees die, if enough new trees are not planted, then we are going to be running into a problem. I think it’s really, really nice right now that there is this renewed interest in it. My question always is, how far it will go, but in a way, that’s a great thing to be thinking about in the future, if it is really something that’s got some momentum.

CR: Looking at our theme of By Chance Or Design, how does a perry pear variety become a named variety, and how does it stand the test of time?

Tom Oliver: First off, obviously, I am no world authority on anything, especially perry and perry pears. I make perry, I do my best to make perry that people will buy. So, if during this discussion, anyone in the room has something to add, I would very much welcome it, because we might all learn from it. I don’t necessarily have huge amounts of information on certain topics. I will say that people don’t think there’s much literature on perry and perry pears. But in actual fact, when you start digging around, there’s a surprising amount and one of the things I would really, really recommend to give you a feel for orchards, fruit, the landscape and everything that we’ve got to so far is, I think this is probably under trust of Jim Chapman, but it’s Understanding Orchards in the Landscape: The Past Determines the Future. It’s a really, really good read. There’s so much great information in there that I would thoroughly recommend it to everyone. You’re going to love what’s in this.

Anyway, perry pears… so the general consideration is, and this may be up for debate, that the true native wild pear growing in British woodland and hedgerows is the Pyrus Pyraster. It is now one of our rarest trees. The cultivated pear, the Pyrus Communis, originated in Central Asia, same as the apple did. It made its way around from Asia, through the trade routes, through the silk routes, through being consumed by bears, camels, humans, and spat out as pips, or the other way things emerge from the body… Italy is the crucial place as far as pears go, I think, in the UK. The work of the Romans, when they were busy trying to conquer us all, they came with pears, and they planted pears. Following their withdrawal, their orchards got abandoned, but the pears they planted started self-sowing, and these seedlings would have crossed with the indigenous Pyrus Pyraster. It’s these crosses, which are often referred to as wildings, or feral pears, are really the ancestors of our native perry pears.

CR: That’s a great account of the brief history of perry pears Tom, and I guess, characteristic-wise, taste-wise, or look-wise, there’s a great variety of shapes, sizes, smells, and tastes?

Tom Oliver: Yes, and you may wonder why are there so many different shapes and sizes around? When the warm period finished, which is, I think between about 950 and 1300 AD, all the vineyards that had been planted, especially by the Romans, they all ceased to be productive because the grapes wouldn’t grow in the ensuing climatic conditions. So they were replaced by orchards. The interest in the fruit of apples and pears started around 1300-1400. By the time we got to 1500-1600, these feral pears that were about, people started attaching significance to them. One of the reasons was not because of the perry pear, if you consider that’s used for making a drink, but it was the pears that were used because we didn’t have potatoes, we certainly didn’t have turnips. We didn’t have root vegetables. The cooking pears were incredibly important to go with the meat and everything that was preserved to eat through the winter. These culinary pears that sort of bridge the gap a lot too. When the root crops came in, the need for those pears diminished, but there were still all these lovely feral pears that people were making a drink from. They wanted to know what the best pears were for making a drink and started deliberately crossing pears, to get something that would be a great perry pear.

CR: We’re not talking pears here like you might find in the supermarket these days, like conference or comice, just high in sugar. Perry pears are wonky in the sense of they can be super high in acid or super high in tannin, and if you were to bite into one of these… it wouldn’t necessarily be a pleasant experience to eat, but if you crush those pears and then you use the juice and you ferment it, that high acid and that high tannin elevates it far beyond its physical form.

Tom Oliver: It makes it suitable for making this drink that we’ll call perry. For the cottagers back in the Middle Ages, they very much had to make a drink that was healthier for them than the available water supply. These acids and these tannins, when they come together, they make a really healthy drink and a really safe drink. Then imagine that something that is both healthier and safer to drink is actually intoxicating and a delightful and pleasant experience. It’s a win-win all around.

CR: Tom, for the audience here that may not have heard of some of the names of perry pears, do you want to read a few out? What I’m pouring now is Blakeney Red, the “Greatest Hits” variety in the perry pear world. It’s the most common variety, but it’s not common…

Tom Oliver: So Jack’s pouring Blakeney Red, which I see very much as the Ford Escort of the perry pear world… it’s generally everywhere and really quite useful when it’s running. When it’s good, it’s good, but when it’s not good, it’s not very good. It’s a very gentle lovely perry.

CR: And it’s from the village of Blakeney?

Tom Oliver: It originates from the village of Blakeney in Gloucestershire, but if you are in Blakeney, I am told you refer to it only as the Red Pear. Because why would you call it Blakeney Red when you’re already in Blakeney… a lot of these perry pears have synonyms. They are known by more than one name in different localities. What are the synonyms for Blakeney Red? Anyone anyone’s read their Luckwill and Pollard?

Audience shouts out: Circus Pear! Painted Lady!

Tom Oliver: Painted Lady yes, why do you think Circus Pear as well Tom? Go on, tell us.

Tom Tibbets (of Artistraw Cider): I was told it’s a very high sorbitol content. It’s a naturally occurring, unfermentable sugar. Which, when taken in large quantity by humans, triggers something known as laxative effects…

Tom Oliver: So yeah, names, other names, too. What’s names would you like to bring up, Jack?

CR: Well, there’s Flakey Bark, if we’re talking rare pears. There’s Coppy, which is very close to your heart. You have pears like Thorn, which are very evocative. Is it named Thorn because it prickles on the tongue or was the tree a seedling and it had these thorny bits on it originally?

Tom Oliver: Well, my Thorn tree at the back of my house, is very prickly, when it’s growing from below the graft. I’m adhering to that, that it’s because it has those kind of barbs on.

CR: What are some of the different landscapes that you’ve found perry pears growing in your career so far? It’s not just orchards, is it?

Tom Oliver: Probably a very indicative example, because I think some of the most impressive trees I’ve seen are the ones in Southern Germany, maybe going into Switzerland, and certainly into Austria, to the Mostviertel. It’s the Southern German ones I find spectacular. These massive trees in the landscape. They are a mixture, I think, probably of named varieties along with seedlings. They’re huge, they were used as boundary markers. They’ve had a mixed history, and much like our perry pears, there’s not as many of them as there used to be. One of the things that happens when you’re making perry and you mix with other perry-makers from around the world is you meet people and you just know what they’re doing is absolutely tremendous. I just want to tell you a little bit about the other regions first: Domfront in France, definitely. Australia, to my delight, when I went out to judge at the Australian Cider Awards a few years ago, there’s a perry-maker who has perry pears that were bought over from the UK at the end of the 1800s. I was drinking a perry that I could readily identify as containing Butt and Gin. These varieties are present in Australia, and they seem very healthy, a little bit more awkward to grow for various reasons. Canada, the Pacific Northwest and sort of all over America, they’re having a go with varieties. But Germany is the one. I don’t know enough to talk about Barry Masterson’s International Perry Pear Project. He gave a keynote speech at our CraftCon this year, what he’s doing sounds phenomenally heavy on the work front and a commitment for the rest of his entire life. He’s trying to gather together a collection of all the perry pears that he thinks are of any significance or interest and get them planted about 90 kilometres southeast of Frankfurt.

CR: Barry is also the editor of Cider Review, he edits all of our work that we send in to him, and he has a main job as well. Just like many of us here in this room, he’s very, very passionate about planting these rare old varieties.

Tom Oliver: The other chap that I’m thinking of is a guy called Jörg Geiger, he started out as a chef. But he’s producing now some very innovative and interesting alcohol-free based beverages. He’s located in Schlat, in Baden-Wurttemberg. It’s the Swabian region. He’s earned a massive recognition for his use of traditional methods and local heritage fruit varieties and has been using the Champagner Bratbirne perry pear for making an absolutely gorgeous, austere, dry sparkling traditional method perry. It’s brilliant. He’s very interested in preserving varieties, in all aspects of growing them, permaculture and everything like that. He’s a tremendous pioneer, and I feel what he’s doing and what he has already done is actually fantastic. If you ever get a chance to go and visit, I urge you to. I have brought along a bottle of his equivalent to what I would call a French Poireau, or an 18-20% abv sweet perry, I don’t know, it’s just beautiful. It’s rich and decadent!

CR: A really widespread smattering for perry pears geographically all across the globe. We can talk about standard trees, these tall trees that can often get to 200-300 years old. But you’ve also seen them growing in the more standard bush orchard type that you might see a lot of apple trees around here in Herefordshire. 6-7 foot high. Is there any difference in the fruit from a bush-grown perry pear tree to a standard?

Tom Oliver: This is going to be a non-scientific answer to that. I generally believe that we are blessed with the work that generations ago went about planting perry pear trees, because I believe the best perry is made from the older trees. By that I mean maybe 100, 200, if you’re very lucky, 300 years old trees. Why that is… I’m going to suggest it’s because these trees have reached a stage of maturity, where they don’t really care what goes all around them. They are looking after themselves. They have a root system and structure that allows them to just be happy. You can’t really do anything to them anyway, pruning them, like not something that you shouldn’t even think about doing. They give you a fruit that seems to have, chemically, the right characteristics to really make great perry. I think this is why they are the better choice.

But, having said that, here we are. We’re in an industry that’s rediscovering itself and trying to progress and move along quickly. A lot of times we don’t have the time, or maybe even the patience, to wait for these trees to come along, because they would have been in the ground 100 years already. So, we’re planting bush trees, and they’re great because they’re all manageable (see National Perry Pear Collection’s trial orchard at Hartpury). They’re easier to harvest, and the fruit you’re getting off them is exactly the same fruit as the ones off the older trees. It’s just sometimes they just don’t seem to quite give you that depth of character, but we’re in a world where depth of character is actually not always what we want. Depth of character can be a bit challenging. So, I’m a believer that, you know, you can make absolutely wonderful perry from trees that are like five years old and producing as long as it’s the varieties you require.

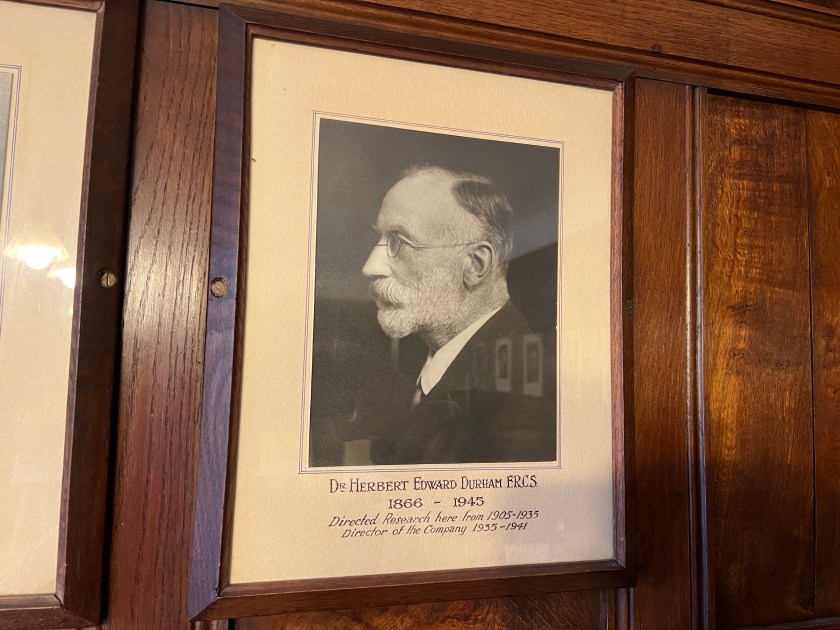

CR: To your left, you have a nice stack of literature, or to be more precise, pomonas and general drinking guides. Could we talk a little bit about a chap called Herbert Durham, linked to this building we’re all sat in, and the lineage from Durham through to books like Charles Martell’s and on the top of your pile, Dave Matthews’ Welsh Perry Pear Pomona. What are Pomonas, and who are some of the interesting characters that have been responsible for creating them every few generations?

Tom Oliver: Yeah. It is interesting that there are several reasons why I think cider and perry had times when they seemed to be in the limelight a little bit, and then times when interest in them disappears and the orchards go to rack and ruin and there’s not much interest in them. These are spurred on by, I think, a lot of the things, the usual things that go on. It could be war; it could be a change in the laws of the land. The Corn Laws made a big difference when they were repealed. When they were repealed, people started planting more orchards because they didn’t need to be planting corn. The legislation that’s in place is important. We’ve already talked about the climatic conditions too. All these things can be affecting the roller coaster ride of perry. But also, there’s individuals.

Character-wise, the first person who really put perry pears on the map was Thomas Andrew Knight. Our friend Darlene Hayes from California is currently researching a book, not so much on Thomas Andrew Knight, but maybe on his daughters, who were responsible for a lot of the illustrated work that was included in his work. They’re local, Downton Castle, so Shropshire, just north Herefordshire. He was the first person to put a Pomona together that had identifiable pictures of named perry pears, around the 1860s. Pomonas are collections, illustrations of varieties of cider apples, perry pear or any fruit, I imagine. This is a beautiful one of Welsh varieties. This is I’ve never seen. There’re various ones and I think, you know, they are all very useful, but they do track the varieties that people are aware of at any particular time.

After that, individual wise, imagine having an MP for cider: CW Ratcliff Cook. Imagine him being interested in what you were doing, and in the varieties that we had in the county, and in helping you establish new varieties, document old varieties, helping you make the drink, all those things. He was a proper champion, rather than some of the false champions we’ve had recently. I shall leave it there.

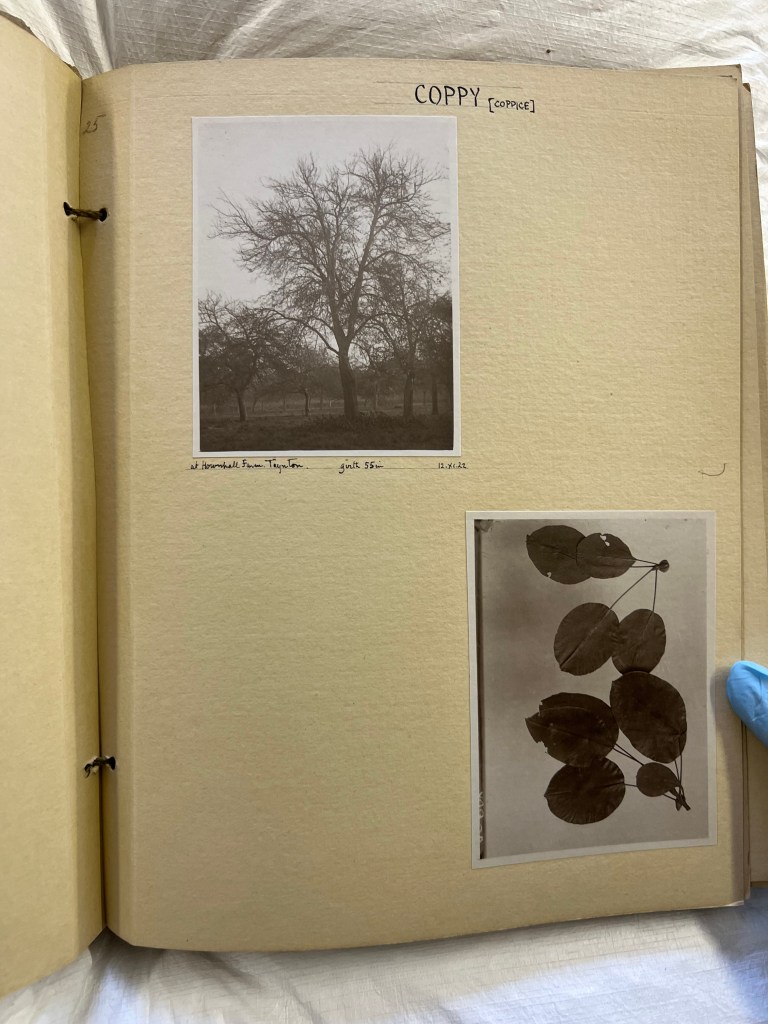

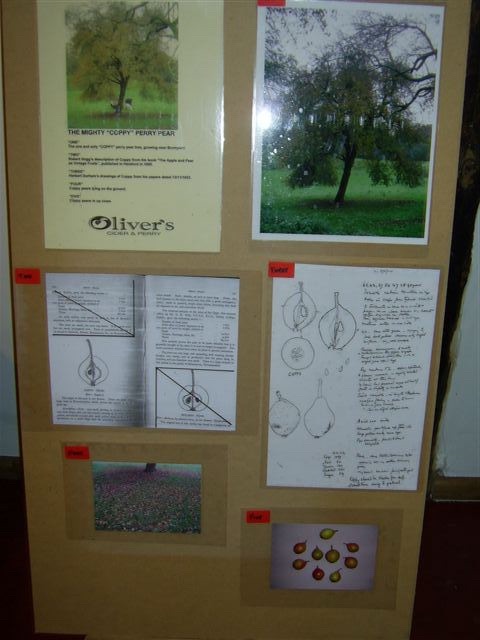

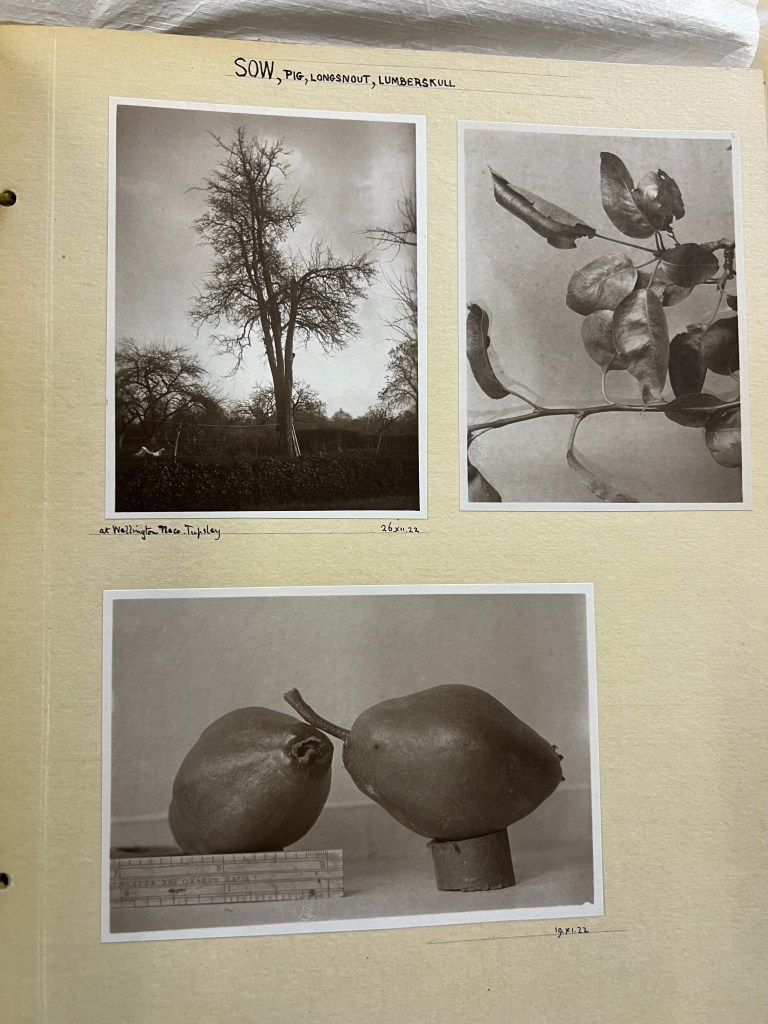

Following CW Ratcliff, now we really come home, to this very building. Herbert Edward Durham. Anyone familiar with him? The chief scientist of Bulmer’s Cider Factory which used to be situated in this very building that now houses the Museum of Cider. He would ride around the countryside on horseback, identifying perry pear trees. He drew dozens and dozens of perry pears and cider apples, including the Coppy perry pear from 1922, they’re just exquisite. Extraordinary gentleman, and very much responsible for, I think, the good times that Bulmers had. He was very well educated. He met the Bulmers boys at Cambridge, and is somebody whose name is not mentioned enough when it comes to talking about Bulmers and their success. he was very, very important.

CR: Downstairs in the collection of perry pears on display, there’s one of his photograph albums, so you can see some of the photos of the old trees that he rediscovered or documented. He died and is buried around Cambridge. After his death, his collection was split up into three parts. Some of his literature and photograph albums came here to the Museum of Cider; some has gone to the Hereford Archive, which you can make an appointment to go and see; then the remainder are in the Woolhope Club Library, which is being redone at the moment, so they’re in a box somewhere. As often happens with these amazing collections, when they get dispersed, that’s when you lose things and that’s when you lose the chance to rediscover things.

Tom Oliver: I came across these, and I had no idea they existed, and it was clear that everyone in the library I went to the Hereford Library (where you’ll usually find the Woolhope Club Library upstairs), had no idea that they existed. I find it just extraordinary. For me, it was like unearthing Tutankhamen’s tomb. It was an absolute revelation.

Moving on to a few more characters, Mr. B.T.P. Barker from Long Ashton Research Station, very much responsible for the book known in the industry as Luckwill and Pollard’s Perry Pears book. It’s a fantastic book. It’s basically the result of the attempt by Long Ashton to plant out in an orchard environment about a dozen or so orchards around different areas of the country, not everywhere, to see how varieties performed over a long period of time. They weren’t talking one year, two years, five years, ten years. They were wanting to look at these orchards for 100 years. Unfortunately, some of them have disappeared: the usual things, not maintained, a son takes over the farm and wants the JCB in amongst the trees etc. But there are still some fine examples of these trees, left.

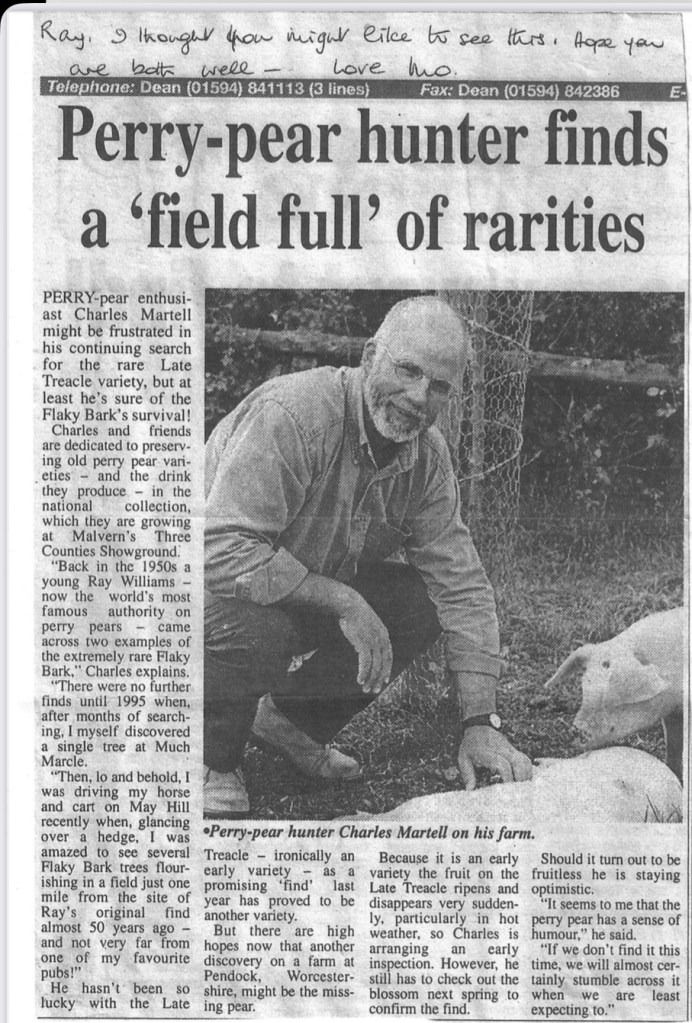

After the work that Edward Herbert Durham did, the next character really to go around the counties, looking at perry pears and trying to work out the varieties was Ray Williams from Long Ashton. He was a tremendous authority on things and passed away 10-15 years ago.

Then the great thing is, we’ve got some modern living champions of perry pears, like Charles Martell and Jim Chapman. It’s extraordinary, the amount of time and effort that Charles and Jim went put into these books. Anyone who was at the dinner last year would have heard me go on about Charles and Jim, I think what they’re doing has been incredible, and I think we’re all really, really lucky that they’ve done it.

CR: Let’s steer the conversation towards a named variety that you are directly responsible for helping rediscover and bring back to the market in drinks form. It’s called Coppy (its photo graces the header image of this article). When you started making perry, did you ever think that you’d rediscover a lost variety? At what point did you realise that this tree you’d been harvesting from was Coppy?

Tom Oliver: This is the encouraging thing for everybody who is as slow and dull as I am, it turned out, that you can be harvesting a group of trees for years and years and years, and you have no idea of its place in the pantheon of perry pear varieties! It took me many, many years to finally work out. It was one particular season when this variety exhibited all the traits that I imagine that Coppy would have. For a number of years, when the fruit was coming off, it didn’t look typical. The fruit coming off a lot of older trees doesn’t always look like the variety that it should be. I was delighted when we thought that it was a half decent variety. It always made really interesting perry. We’ve got a lot of fruit on the tree this year.

CR: What’s the orchard like that the Coppy tree is in?

Tom Oliver: It’s a classic old Herefordshire mixed farm orchard. There’s lots of old cider apple trees there. There’s a lot of perry pear trees, too. It’s just outside Bromyard. The interest in it has always been phenomenal, but you know, the real thing is that it’s just a great perry pear. In 1898 or near abouts, at Rye Court, which is sort of near between Ledbury and Birtsmorton, there was a 10-acre orchard of this particular variety. Just planted with Coppy. Just before 1900, a 10-acre site and it was not the only one. It was a widely grown perry pear. It seems almost inconceivable to me that now this one tree that I’m picking is the only one that’s come through in terms of the DNA identification. How can it be the only mature one left? I find it almost impossible to believe.

CR: In Luckwill & Pollard’s Perry Pears book, out in the 1960s, it’s already listed as an uncommon variety. Then between the ’60s, and when you rediscovered it, it was considered extinct. It shows how quickly the fate of a variety can change…

Tom Oliver: I would be delighted if someone found another one, because it would almost make you feel like it was a normal variety again. It does go to show you this concept of threat that we started talking about. It’s very real and it doesn’t take many years for it to go from something that is been widely planted and thought of very highly to being… So the question is what stopped Coppy from being a widely used perry pear? I think it’s because it was probably far too small and probably infrequent in terms of giving a decent crop. When push comes to shove, you’ve got to perform well in the orchard, and then in the bottle. The field that the Coppy tree photo in Luckwill & Pollard’s Perry Book displays is now an open cornfield.

I live in a village called Ocle Pychard, and in 1636, a guy called Silas Taylor lived there. He was like the audit guy for cider and perry in the county for the government back then. He talked of a tree, obviously that had been going for hundreds of years, and it gave off massive crops. The idea that in my own village 400 years ago, there was this phenomenal tree that the leaves glistened dark green and everything. Where is it? Where was it? I have made no progress finding more information about it…

CR: This brings us back to the chance and design element of our topic of conversation really with Coppy. It was by chance that the seedling was a good one, and then by design planted widely, then lost and rediscovered by chance again. Hopefully you’re the catalyst for the next wave of Coppy plantings. Maybe we’ll see Coppy appearing in plant nurseries soon?

Tom Oliver: I think maybe does that not open the conversation up to this idea that we’re suggesting that all perry pears that are part of contemporary perry-making culture were once feral pears? Is the future for perry going to involve this discovery of new varieties? I don’t think there’s many feral or wild ones left in the UK. It’s just the nature of the landscape here doesn’t allow that. There might well be in America, the opportunity certainly exists for apples,

CR: Are there any other lost varieties that you would be interested in rediscovering? I know that Jim and Charles are very actively looking for the Treacle Perry Pear (either Early Treacle or Late Treacle). It’s mentioned in Charles’ book. There’s loads of literature about it. Durham covered it. It’s in the Luckwell and Pollard too.

Tom Oliver: I certainly think one variety brought back from the brink is enough per producer, but the question is, of course, is the variety that you’re picking that you don’t know the name of that lost variety? Because it could quite easily be. Kevin Garrod, here in the audience of Monnow Valley Cider, helped rediscover Betty Prosser.

Kevin Garrod: I pick a little couple of orchards in the Monnow Valley, so on the border with Herefordshire and Monmouthshire. I rediscovered Betty Prosser, presumably the origin of the name comes from Monmouth. I sent these pears to Jim Chapman over a number of years, and we managed to pin it down to this particular variety, four trees in one orchard, another one just the road, literally half a mile away from those trees. Betty Prosser was meant to be an extinct variety, and now I’m making perry with it, and a couple of other people do too. For a while you just chuck these pears in with other known ones to make a blend, but I like to make single variety perries, so to know what this and that tree are is invaluable. You want to know what you’re using.

CR: Tom, could you tell us a little bit about the Bulmers’ perry pear orchard? We’re here in the Museum of Cider, which used to be the centre of Bulmers’ activities. It seems that the Bulmers perry pear orchard was somewhere that populated a lot of subsequent peoples’ orchards. I know Mike Johnson, at Ross Cider, got a lot of his perry pear trees from there, and were already 10 years old when he bought them.

Tom Oliver: A lot of my trees came from Bulmers. I think it was at Broxwood, this particularly perry pear orchard. I don’t know if it’s there anymore. I’m presuming it isn’t, but it may. John Worle got a lot of his mother tree wood from that orchard for his nursery. But that’s no more. I think it’s like all these things, it’s an ever evolving, moving thing, and if you take your eye off it, things will disappear very quickly. So if you’re a propagator and you have a nursery, then you have a mother orchard that you’ve developed over 50 years. But if you retire, and no one takes over the business or the land gets sold, then that could easily wipe out potentially, the result of your lifetime’s work, and this is the real problem. We just need a little more help. Money has got to come from somewhere to achieve all these things, but we do need to look more seriously at this help in the future of these varieties. Otherwise, you know, we’re gonna get unstuck again when the enthusiasm and the energy, that the youth that people like you Jack, and so forth are bringing to this whole thing again. When that fades, we don’t want to go back down to nothing again, and then spend 100 years for it to be discovered again.

CR: Could you talk a little bit then about this year’s CAMRA Pomona Award winner: the Hartpury Orchard Trust, home of the National Perry Pear Collection?

Tom Oliver: I think it’s just brilliant. Everyone mentions Jim Chapman nowadays, but you know, he was a practising solicitor in Newent until 20 years ago, looking after a Victorian village, which was his passion. Jim’s an extraordinarily interesting man. He’s very passionate about where he lives, which is Hartpury. I would hate imagining Jim being born somewhere where the perry pear didn’t exist, because his whole life has led to the moment of Hartpury being the village of the hard pear. Everything that he’s done in the last 20 years has been focussed around the perry pear. It’s extraordinary, the efforts that he has gone to help preserve these varieties by establishing, not one, but at least two national collections, and a further bush orchard as well. Isn’t it odd people in their gardens having perry pear trees? It shouldn’t be.

CR: So, Tom, what advice could you give to someone, maybe someone in this room, (or reading this article online) that’s interested in going out and looking for lost perry pear varieties?

Tom Oliver: I think it would be a very, very interesting thing to do, because it would get you around. If you wanted to have a reason to get around the county, and you didn’t want it to be all consuming, you could wait till May, wait to see this lovely white blossom on these older trees, these massive big trees. That would give you an excuse to go and see the landowner. Obviously, you’ve got to be able to run. You’ve got to have a good pair of shoes on you. You’ve got to be prepared for some interesting language, which you may not understand half of it, but it might end with “… off”, all right? On the other hand, you might meet some really lovely people who are just delighted that someone’s taken an interest in something that’s been growing in their field for 100 years and they haven’t really bothered about it but have always wondered.

I’ve had some really interesting experiences, going around places. Like everything in life, if it’s not used, it’ll not have a future. So we need more people making great perry, I think, it’s the real key to it.

CR: Has there been a tree, it can be named or semi wild, that you’ve either used and then lost, or one you thought, I’m going to go to that tree, and then next time you come back, it’s been struck by lightning or an estate’s being built where it was?

Tom Oliver: I’ve never picked something and have wanted to go back to or missed or anything like that. But I have been to an orchard in Ashleworth in Gloucestershire, where there are three amazing old Yellow Huffcap perry pear trees, great big monsters, where the fruit never falls off, when it does, it’s rotten. The owner always texts me every year there’s a lot of fruit, you know, come and get it, and I go, oh yes, please. And even if I go, you end up with very little. I think it’s worth it, but it’s very little. Anyway, growing in his orchard, there is something that looks like an apple, but it doesn’t taste like an apple, looks like it, doesn’t look like a pear, but tastes like a pear. What I do want to do is go back and one day actually explore what that is, because I’ve got no idea what it is. That’s the only thing I’m thinking of…

I hope you all enjoyed delving into that talk with Tom Oliver at PerryFest 2025. In my previous working life, in which I was privileged to host innumerable live Q&As with directors and actors from the arthouse cinema world, there were certain sessions in which you had to prep hard with all the right questions, that you hoped would engage the audience and eek out a few impromptu questions from them as well. Then there were others which the script of questions flowed freely, conversationally, and the event itself went by in a flash. This talk with Tom was just that kind of In Conversation. We could have spoken for easily another hour, gone down many fascinating rabbit holes and elicited countless more anecdotal gems to share with the audience. Such is the ease of conversation when dealing with a consummate professional like Tom Oliver, absolutely at the peak of his powers, with decades of working knowledge behind him.

This talk made me think how fortunate that Coppy tree – a potential lone survivor from a time in the past of multiple 10-acre orchard sites – was to have Tom Oliver as the next generation of perrymaker to come and harvest fruit from under its boughs. Similarly with Kevin Garrod of Monnow Valley Cider sat in the audience, how blessed are the few remaining veteran Betty Prosser trees that it was Kevin who decided to dedicate time every year to studying the fruit, cross-referencing it with Jim Chapman, and subsequently DNA testing it too. Maybe it was chance, maybe it was fate, that these individuals showed a level of care and attention to give these varieties their name back. There’s something incredibly honourable about that in my mind. With it comes a deep respect for the history of these varieties, alongside a re-affirmation of the farmers, perrymakers, and botanists that were responsible for initially cultivating these perry pears in the first place.

Tom touched on the aspects of going out and starting a journey of re-discovery towards lost perry pear varieties. Just over a year ago, I decided I would delve a little deeper into one specific lost variety: Cheat Boy. More on that adventure to come in an article or two on Cider Review in the months ahead. What I would say, is that Tom’s advice to me: to not be afraid of a bit of random door-knocking – you have to get out there and be the catalyst in the situation – has proved incredibly fruitful. I would encourage anyone with a bit of spare time and a whole bunch of passion for the subject matter to pick up Charles Martell’s Perry of Gloucestershire and Perry Pears of the Three Counties, it’s the best starting point for understanding what’s out there currently, and what may still be around in hedgerows or overgrown abandoned orchards. You’re now living in a world with not one but two National Perry Pear Collections; a DNA database to cross-reference results and really deep-dive into its spreadsheet of stats; and a number of internationally recognised producers of single variety perries that allow you to build up your own opinions on which flavour profiles from different varieties you love. It’s an exciting thought that a reader of Cider Review could be responsible for helping to bring back Satoo, Sow Pear, or Spice Pear from obscurity, and help to re-unite the Hatherly Squash, Oak Verlan, or Red Huffcap with their names once more. I look forward to seeing the results of your endeavours in the years to come!

Discover more from Cider Review

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

An absolutely extraordinary interview. Thank you Jack for transcribing this and travelling to the Museum of Cider for Perry Day in the first place. Thank you Tom Oliver for being so generous and fantastic with your knowledge and passion. Perry is ALIVE!!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

My pleasure Albert ☺️ Glad you enjoyed the interview 🍐🎉🍐

LikeLike

He refernces “Understanding Orchards in the Landscape: The Past Determines the Future” but I cant find this – is it a book, article??

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hey Justin, I think from memory this is a little ring bound book that Jim Chapman wrote. He had some for sale at the Malvern Autumn Show this year, so I imagine copies are for sale at events that Jim attends.

LikeLike