In April 2024, Cider Review highlighted the ever-growing threat of fireblight to the UK’s cider and perry industry, concluding with a call to arms for greater cooperation, research, and knowledge-sharing to regain momentum in the fight against the disease which had fizzled out over the past 66 years. In that spirit, this article looks back at the efforts of fruitgrowers, government scientists, politicians, and civil servants to protect their fruitgrowing industry in New Zealand against fireblight 100 years ago.

The fireblight bacterium, Erwinia amylovora, is native to North America, and it’s thought to have remained confined there geographically since its discovery in the late 18th century until around the start of the 20th century. By 1900, fireblight was largely endemic across the United States and Canada, and fruitgrowers, scientists, and government officials had largely accepted that the disease was a serious, but manageable, fact of life. They worked on developing ‘blight-proof’ varieties and rootstock which were less susceptible to the disease, and compiled lists of orchard management strategies which could help to protect trees against a serious outbreak. Fireblight could mean financial loss, but it was no longer considered wholly devastating or a threat to the fruitgrowing and cider-making industries entirely.

Fireblight was first officially reported to have left North America with an outbreak in the Auckland Province of the North Island of New Zealand in December 1919. Believed by the New Zealand Department of Agriculture (NZDA) to have been imported from the United States on infected nursery stock, fireblight was soon observed in the apples, pears, and quinces within that province. Examining the response to the disease in New Zealand in the decades immediately following the discovery of fireblight in Auckland allows us to look back on the control efforts and – hopefully – glean some insight into the kind of approach to take now in the UK.

Background: Fruitgrowing and cider-making in New Zealand

Agricultural production has long been central to New Zealand’s economy. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, New Zealand was a dominion of the British empire; agriculture and agricultural exports provided a vital and valuable way of strengthening ties between the two countries. Between 1875 and 1890, New Zealand underwent an economic downturn called ‘the long depression.’ The invention of mechanised refrigeration and the establishment of a regular steamship service to Britain provided access to British markets for New Zealand’s produce from the 1880s onwards and a way out of this economic slump. This strategy proved incredibly successful, but it also meant weakness: New Zealand’s economy was almost entirely dependent on the sale of its produce in Britain. By 1920, New Zealand sent at least 75% of all of its exports to ‘the old country’, and sourced around 50% of all its imports from Britain, too. In this context, fruitgrowing in New Zealand had developed from small commercial orchards growing for home use and the local markets in the late 19th century to an export oriented industry by the 1910s. While it was certainly important to grow enough fruit and produce enough cider for the home market to avoid reliance on slow and expensive imports, emphasis was placed on providing the best exports to Britain. Historians agree that during this time, farmers became the ‘backbone of the country’ as the standard of living for all New Zealanders rested on the quality and quantity of agricultural produce.

In 1892, the New Zealand government created the New Zealand Department of Agriculture (NZDA) to provide farmers with ‘expert scientific advice’ to improve and intensify primary production in the dominion. This marked the beginning of an era of strong government involvement and support for agriculture and agricultural science. In 1893, the NZDA appointed two pomologists, later known as ‘orchard instructors’ to support New Zealand’s orchardists. Their numbers grew from two in 1893 to 29 by the end of the 1930s. These orchard instructors had lengthy practical experience in fruitgrowing and were employed to keep up to date with the latest scientific research and communicate the practical implications to fruitgrowers. Furthermore, they conducted their own experiments with newly invented pesticides and fungicides to determine the most effective sprays to protect New Zealand’s fruit trees from insects and disease.

From a purely economic standpoint, fruitgrowing was considered to be one of the ‘lesser primary industries’ in contrast to meat, dairy, and wool production by the NZDA. However, being in the southern hemisphere provided New Zealand fruitgrowers with an advantage; their apples could be sold in Britain when British, North American, and European apples were out of season. Between 1900-1920, New Zealand underwent what historian Gerald Ward termed a ‘planting boom’ and vast swathes of new orchards were planted. This ‘boom’ peaked at about 36,000 acres in orchard in 1916. Fruitgrowing was considered a sound financial investment. Government support, local demand, and a ‘practically unlimited’ overseas market combined to create the idea of the life of a commercial fruitgrower depicted as an ‘easy and pleasant way to make a good living.’

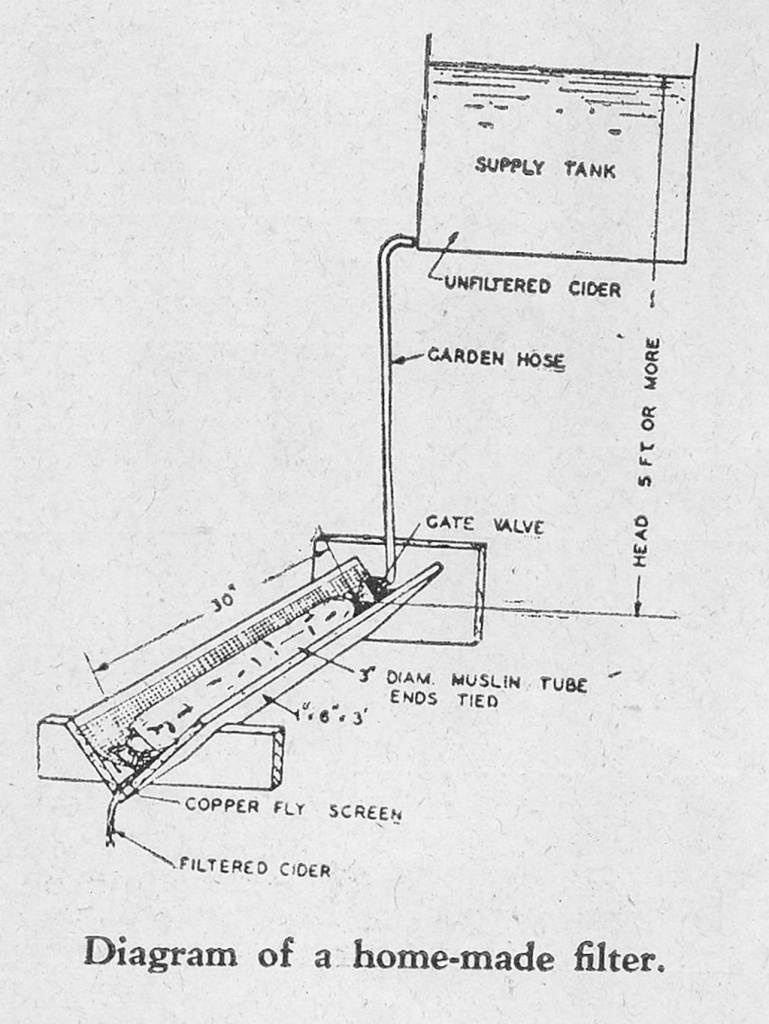

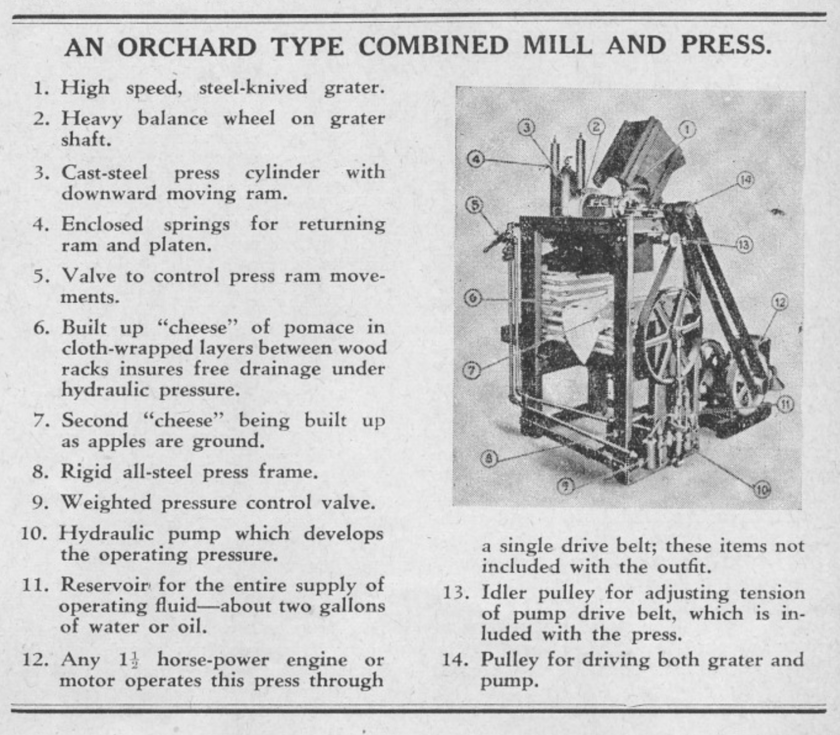

As part of the dominion’s economic strategy, fruitgrowers aimed to export only the highest quality fruit for British markets. Consequently, cider-making was an important aspect of the fruitgrowing economy, and the NZDA encouraged growers to use any apples that were not of the highest quality to make cider instead. Fruitgrowers were advised that ‘with the increasing production of apples in the Dominion and the high standard required’ for exports and the home market, ‘the manufacture of cider may be looked upon as a most important safety-valve for the New Zealand apple industry.’ This advice proved popular, and by the mid-1920s anywhere between 50,000-60,000 gallons (227,000 -273,000 litres) of cider were being produced each year. The equivalent financial value of this today would be in the range of millions of pounds. Like the apples being sold in Britain, it was important that this cider was also ‘good quality’, and orchard instructors provided New Zealand fruitgrowers with detailed advice and descriptions of the most up-to-date methods and equipment.

Concerns among New Zealand fruitgrowers and the dominion’s government about bio-invasion and the effect of pests and diseases on fruit trees can be traced as far back as 1884 with the Codlin Moth Act, the Orchard and Garden Pest Acts in 1896 and 1903, and the Orchard and Garden Diseases Act in 1908. As a result of this legislation, orchard instructors (acting in their role of disease inspectors) were key representatives of the NZDA, its research, and support for growers in the local community. New Zealand fruitgrowers enthusiastically participated in a close relationship with the NZDA, lobbying legislators for an additional tax to be placed on their orchards, the proceeds of which would go towards funding research into New Zealand fruitgrowing and protecting orchards from pest and disease. The novelty of a group of people asking to be taxed more was not lost on New Zealand lawmakers!

By the time Fireblight was discovered in New Zealand in 1919, there was a clear precedent of government intervention, legislation, and concern about importing pests and diseases and their spread throughout the dominion’s orchards. Fruitgrowing and cider-making was a small, but important, part of the economic backbone of the country. The ‘dread American fireblight’ posed a catastrophic threat to this status-quo.

Waging war on fireblight.

The arrival of fireblight – and its potential impact on New Zealand’s orchards – captured public discussion in a way unlike the conversations in North America. From the outset, government scientists, fruitgrowers, politicians, and journalists were all quick to declare that an unchecked spread of fireblight that became endemic, as had been the case in North America, would become a ‘devastating scourge’ and a ‘menace’. It was argued that the survival of New Zealand’s young orchards – most of which had been newly planted in the ‘boom’ of the 1910s – hinged on complete eradication of the disease.

The disease arrived in a time which historians have considered to be a period of successive crises for the country. In 1919, New Zealand had very recently undergone two deadly traumatic events – the First World War and the ‘Flu pandemic (also known as the ‘Spanish ‘Flu’). A good deal of the public discourse surrounding fireblight in the newspapers of the early 1920s reflected New Zealander’s patriotic ‘British’ identity and their involvement in the First World War.

New Zealanders’ long-held concerns about bio-invasion were combined with their recent traumatic experience of the war. Newspaper articles portrayed fireblight as a hostile foreign invader of their islands. One newspaper article, written by a concerned fruitgrower, made the link clear: ‘fire blight has invaded and is in New Zealand, consuming the produce of our lands from which we obtain our living. Is there much material difference in the result between fighting Germans and germs?’ The effort to protect New Zealand’s fruit trees was portrayed in the press as a heroic fight. Orchardists were encouraged to make sure their orchards were ‘patrolled’ and those who were successful were reported to have engaged in ‘a splendid fight to eradicate the disease’. To refuse to help the cause was declared ‘unpatriotic’.

The fact that fireblight was a microscopic disease which originated from the United States was also not lost on commentators at the time. The 1919 ‘Flu pandemic had also reached New Zealand from an American source and was also considered a ‘devastating

scourge.’ Coming immediately after the First World War, this deadly pandemic was also a crisis for New Zealanders and so it is unsurprising that news of another supposedly deadly germ with foreign – American – origins captured the imagination of New Zealanders, with its reputation as ‘the dread fireblight of America’.

It is always hard for historians to accurately assess how ordinary people felt about historical events. However, it is safe to say that this public discourse among fruitgrowers, scientists, and journalists from the outset likely put a good deal of pressure on the New Zealand government and the NZDA to intervene. The precedent of government support and legislation concerning fruitgrowing over the decades preceding fireblight’s arrival in the dominion meant that it was relatively straightforward for the NZDA and the government to amend the Orchard and Garden Diseases Act to include fireblight. While that might have been considered ample protection by North American fruitgrowers, who had accepted that the disease was endemic and focused primarily on mitigating the damage that a likely outbreak could cause, this was not enough for New Zealand. It was accepted by the government, the NZDA, fruitgrowers, and the press that mere control within the orchard was not acceptable. The disease could not be allowed to spread and, ideally, had to be eradicated completely.

This goal of eradication meant that in the early years of the 1920s the NZDA engaged in a flurry of research and knowledge-sharing with their counterparts at the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Of particular interest to the NZDA was how fireblight could spread outside the orchard through host insects and plants. Telegrams were sent between Wellington and Washington, and in 1923 American scientists at the Universities of Cornell and Wisconsin sent samples of fireblight bacteria for NZDA scientist, Richard Waters, to compare with samples from New Zealand. As a result, Waters developed the first laboratory diagnostic test for the disease. The NZDA discovered a handful of new hosts of fireblight – native New Zealand insects and plants – which could transmit the disease across the country. The biggest concern, however, was hawthorn.

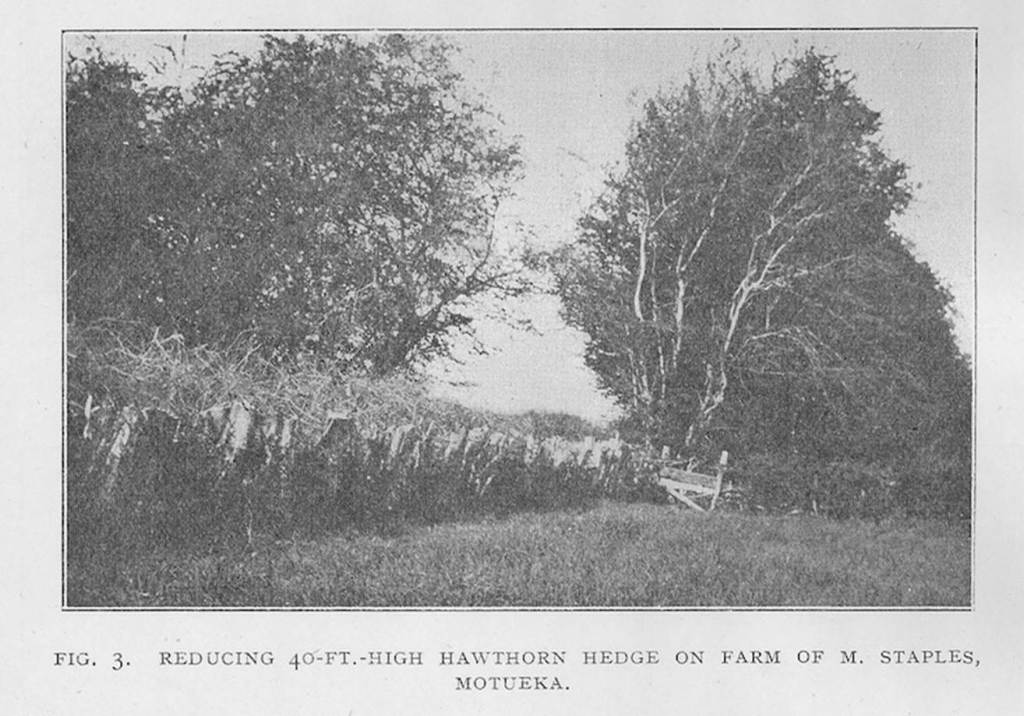

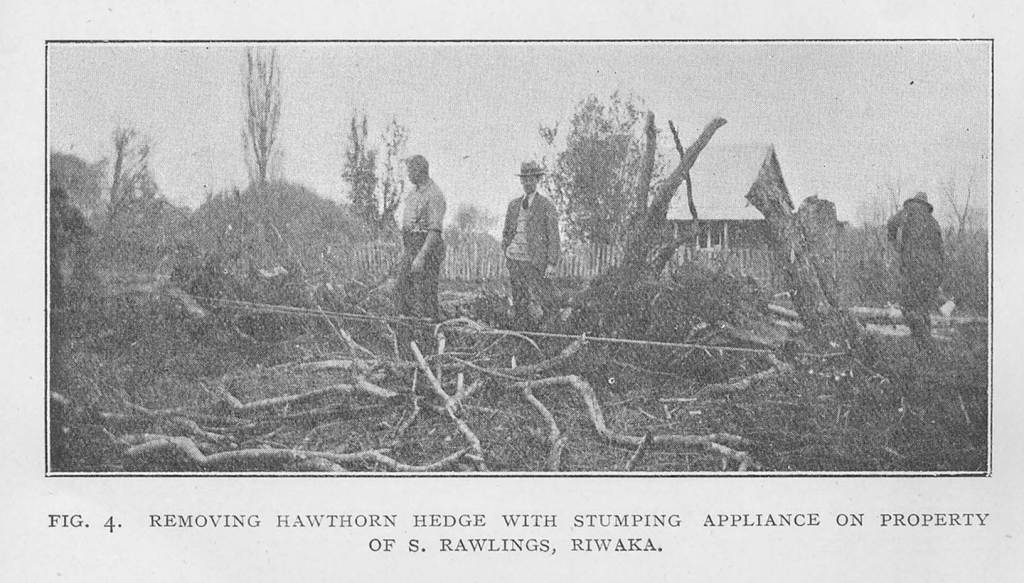

Hawthorn hedges had been introduced to New Zealand by British settlers in the 19th century and were primarily used by farmers in place of fencing throughout the countryside to provide shelter for livestock. Hawthorn is a member of the Rosacea family and is susceptible to fireblight, but can withstand the disease better than apples, pears, and quinces. The thousands of miles of hedges throughout the countryside in the North and South Islands had the potential to provide the perfect route for the fireblight bacteria to travel. It is unsurprising that, in response to this news, the press began to label these hedges as ‘the hawthorn menace’, too.

The government and NZDA’s first response to this information was to amend the Noxious Weeds Act in 1921 to include hawthorn in the list of plants which could no longer be purchased or distributed. Local authorities were given the power to require the control or removal of hawthorn in their jurisdiction, if they saw fit. However, fruitgrowers and their MPs complained that the effect of this Act was inconsistent. If the local council was primarily made of up livestock farmers who didn’t want to remove their hedges, there was nothing to compel them to do so. In 1922, the NZDA collaborated with New Zealand’s fruitgrowers to develop more consistent legislation, and the government introduced the Fireblight Act. The Act was an extension of the powers outlined in the 1908 Orchard and Gardens Diseases Act. William Nosworthy, the Minister for Agriculture at the time, argued that fireblight needed its own regulations because it was ‘in a different category from other orchard diseases’.

The Fireblight Act, passed in October 1922, repealed the Noxious Weeds Amendment Act (1921) and any special orders made by local authorities relating to hawthorn. Instead, the Governor-General of New Zealand was given the power to ‘declare any specified portion of New Zealand to be a commercial fruitgrowing area.’ These areas were protected under the Act through strict trimming schedules for hawthorn to prevent flowering or additional growth. If a fireblight outbreak was discovered in a commercial area, any hawthorn in that district had to be destroyed within a specified timeframe. Unlike the Noxious Weeds amendment, power to enforce this control of hawthorn was removed from local authorities and centralised under the Governor-General, the Minister of Agriculture, and officers of the NZDA. ‘Fireblight Committees’ were formed in these commercial areas. Directed by their local orchard instructor, they undertook the work required to identify and remove outbreaks of the disease in orchards and other host plants. The New Zealand Fruitgrowers Federation also successfully petitioned the government to increase the Orchard Tax to include a fireblight levy that would be charged in the commercial fruitgrowing areas to help fund the disease control efforts.

Did this approach work?

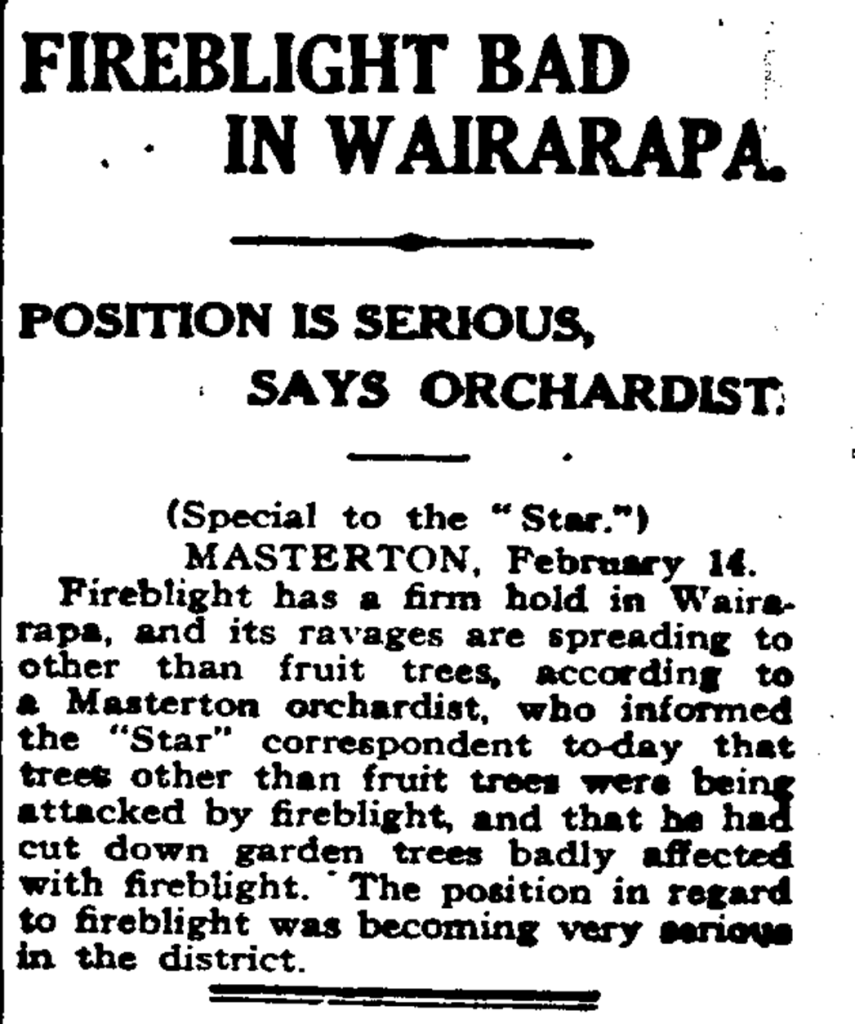

If we measure the effectiveness of the New Zealand approach to fireblight solely through the metric of the NZDA’s goal of complete eradication, the answer is a resounding no. Fireblight continued to spread throughout the North Island in the 1920s. The disease crossed Cook Strait and was reported in the South Island in 1929. As the 1930s progressed, fireblight continued to spread southwards, reaching the Otago region, for example, in 1936. However, the spread of the disease was not as rapid or destructive as the NZDA had predicted in 1919, and this slow progression is likely the result of the legislation and control measures put in place. Some years, such as 1924-5, were even considered record years for apple production. It is difficult to find any concrete statistics about the damage fireblight caused in New Zealand’s orchards or if there were any repercussions for the cider industry during this time. The NZDA’s annual reports do not consistently contain statistics about fruit or cider production and discussion of fireblight is usually contained to naming the places where the active outbreaks of the disease had been discovered that year. The most frequently given explanation of disease control work was that ‘every effort was made to confine it to the areas already infected.’ These efforts were, ultimately, unsuccessful and fireblight occasionally caused ‘severe losses’ to fruitgrowing regions, like Hawkes Bay in 1927.

Where fireblight control in New Zealand came unstuck was the careful balancing act the NZDA had to perform between supporting fruitgrowers and protecting the interests of other sectors of agriculture. Lawmakers were sympathetic to fruitgrowers, who were ‘much concerned’ about the ‘ravages of fireblight’ and understood that the disease needed to be ‘attacked in a systematic way’ otherwise it could deal ‘a very serious blow to the fruit industry.’ On the other hand, livestock and dairy farmers contributed a good deal more to the dominion’s economy and were a core demographic of the electorate – particularly for the Reform Party, who were in power for much of this period.

The nature of the Fireblight Act meant that hawthorn eradication and control was piecemeal, confined primarily to those areas designated as ‘commercial fruitgrowing districts.’ Even then, politicians had recognised that there had ‘been many bitter complaints’ that it was ‘almost an impossibility to eradicate hawthorn.’ Many owners of hawthorn hedges in these commercial fruitgrowing districts were livestock farmers who could not afford the cost of removing the many miles of hedges and replacing them with a different type of fence. While fruitgrowers’ panic surrounding fireblight remained vague and nebulous – very rarely, if ever, did growers or their MPs give any statistical evidence about the loss of yield or money that the disease caused – livestock farmers and their MPs were clear about the cost of removing hawthorn. It was estimated in the 1920s that the cost of doing so could fall anywhere in the region of £200- £300 per mile – equivalent to well over £10,000 per mile today. They held out on removing the hedges for as long as they possibly could for fear of bankruptcy.

Fireblight did not damage hawthorn in the same way as it did fruit trees; the hedge could continue growing for a good deal of time once infected. As Richard Hudson, MP, pointed out in 1927, ‘that makes the position more extreme, because the hedges are there, and they are useful.’

Politicians debating fireblight control frequently addressed the question of compensation for those required to remove their hedges. This was also something the livestock and dairy farmers lobbied their representatives for; they received compensation for the destruction of diseased cattle, why not their diseased hedges? The NZDA continued to refuse the option of compensation, arguing it would be too costly to the taxpayer. Furthermore, in 1928 the Minister of Agriculture, Oswald Hawken, argued that it was ‘an unsound argument’ to equate the ‘destruction of an animal at an abattoir’ to the removal of hawthorn hedges. The destruction of cattle was ‘for the protection of public health’ and, clearly, ‘public health’ was only applicable to human health. Hawken and the NZDA were reluctant to allow this notion to spread to include the health of plants or the economy.

What can we learn from New Zealand’s experience?

Despite the best efforts of the NZDA, scientists, fruitgrowers, and legislators, fireblight continued to spread throughout New Zealand. Ultimately, hawthorn continued to grow in New Zealand because it was too expensive to compel its complete destruction; the protection of commercial fruit districts would have come at the cost of the largest sector of the economy. While orchard instructors and fruitgrowers could control an outbreak within an orchard through regular inspections and pruning at key times of the year, the persistence of hawthorn throughout the North and South Islands provided an environment where the fireblight bacteria could survive throughout the winter. In spring, the hawthorn would bloom, and bees and other native pollinators would become carriers of the blight bacteria, spreading the infection to the tender, susceptible new growth of fruit trees.

Clearly, eradication of fireblight in the UK is not something we can hope for. The disease has been present in England for over 60 years and to eradicate it completely would require an immense overhaul of the countryside, legislation, scientific research, and a good deal of funding. Even then, the case of New Zealand shows that such efforts are not guaranteed to work. There is only one supposed case of successful fireblight eradication – Australia around the year 2000. Fireblight, then, is in the UK to stay.

If eradication is not the answer, damage limitation and risk management might be. While New Zealand’s approach to fireblight eradication was not successful, I would argue that it was not wholly unsuccessful and – importantly – there is a good deal we can take away from it when thinking about protecting orchards in the UK. I think the NZDA were right to view fireblight as a disease that affected more than just fruit trees, fruitgrowers, and the fruit and cider industries. Up until that time, the approach to fireblight in North America had been primarily concerned with the pathogen and its interactions with fruit trees. Comparatively minimal time and effort had been spent to understand the disease beyond the orchard. With New Zealand’s eradication approach, NZDA scientists, civil servants, and legislators necessarily had to think about the disease more broadly and understand how it could spread from orchard to orchard. And, crucially, how that understanding could be used to prevent this spread, the overwintering of the pathogen and ‘spontaneous’ outbreaks.

The contrast of fireblight control efforts in North America and New Zealand in the 19th and 20th centuries with the approach in the UK in the 21st century is striking. Guidance surrounding fireblight, and its place on the list of notifiable plant diseases in England, was withdrawn in October 2019. After 66 outbreaks in June 2024, officials in Jersey – one of the last few ‘fireblight free’ areas of the UK – gave up the ghost and removed fireblight from its list of notifiable diseases, too. When researching this article, a key question occurred to me as I was tracing the decline of fireblight control in the UK: Was there ever any kind of knowledge exchange between the government authorities tasked with controlling the disease and the fruitgrowers whose livelihoods were at risk? There certainly was historically in New Zealand and North America. That the change in the UK was so recent, yet fruitgrowers feel so overwhelmed and under threat from fireblight – as so emphatically shown in Laura’s article last year – suggests to me that there was not.

What also became strikingly evident is how difficult it is to actually trace UK government guidance and regulations for fireblight. I say this as someone who has a PhD in the history of fireblight research and legislation! A centralised, effective approach for tackling the disease in the UK is not clear. Yes, there are factsheets about fireblight available from sources such as the Royal Horticultural Society, but it is not clear how helpful this advice is for those who make their living from growing pomaceous fruit and the production of cider and perry. The Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) risk matrix for fireblight suggests that there will not be any efforts from that department in the near future to research, regulate, publicize, or perform contingency planning for the disease.

My own research into fireblight has focused primarily on the interactions and relationships of the communities who encountered it, how they studied the disease, and shared their knowledge about it. I wholeheartedly echo the call for more knowledge-sharing now. We need to be having more conversations about fireblight, the damage it can cause the UK cider and perry industry, and how we can manage this risk. Certainly, these conversations need fruitgrowers at the core, but perhaps we can take a leaf out of New Zealand’s book and include rural communities more generally. Yes, fireblight predominantly affects pomaceous fruit trees, and cider and perry varieties are particularly susceptible. But fireblight also infects a variety of other local flora and it is this flora that could hold the key to understanding and preventing further outbreaks in British orchards. By viewing the disease more holistically, perhaps we can better protect the UK cider industry in the future. Fruitgrowers and cider-makers may not be able to legislate fireblight away, but, with cooperation and communication, we can try to fix the knowledge gap.

Bibliography

For in-depth discussion of Fireblight in 19th and 20th century North America and New Zealand, including specific citations, see: Bruce, Kathryn Emma. ‘The Fireblight Menace : Knowledge Communities and Their Response to Crop Disease in the Anglo-World, 1880-1939’. Thesis, The University of St Andrews, 2025.

For the fact-checkers and curious:

BBC. ‘Fireblight Fruit Tree Disease Established in Jersey – Government’, 20 August 2024. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c93p9lvlw46o.

Belich, J. Making Peoples: A History of New Zealanders. (Auckland: Penguin, 2001).

‘Cider-Making: Practice for New Zealand Conditions’. New Zealand Journal of Agriculture 28, no. 2 (1924): 92.

‘Cider-Making’. New Zealand Journal of Agriculture 35, no. 5 (1927): 356.

‘Cider-Making’. New Zealand Journal of Agriculture 39, no. 4 (1929): 266.

Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. ‘UK Plant Health Risk Register’. Accessed 30 April 2025. https://planthealthportal.defra.gov.uk/pests-and-diseases/uk-plant-health-risk-register/viewPestRisks.cfm?cslref=11792.

Fireblight Act, 1922 (13 GEO V 1922 No 20), 1922.

GOV.UK. ‘[Withdrawn] Disease Control in Flowers and Shrubs’, 10 October 2019. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/disease-control-in-flowers-and-shrubs.

Hyde, W.C. ‘Replacing the Hawthorn Hedge’. New Zealand Journal of Agriculture 36, no. 2 (1928): 94.

Keil, H. L. and T. Van der Zwet, Fireblight a Bacterial Disease of Rosaceous Plants, USDA, (1979)

Lindeman, B.W. ‘Points in Making Cider: Diagram of a Home-Made Filter’. New Zealand Journal of Agriculture 62, no. 4 (1941): 280.

Lindeman, B.W. ‘Points in Making Cider’. New Zealand Journal of Agriculture 62, no. 5 (1941): 359.

Mein Smith, P. A Concise History of New Zealand. 2nd ed. Cambridge Concise Histories. (Cambridge:Cambridge University Press, 2011)

New Zealand Department of Agriculture, Annual Reports, 1920-1939. Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/parliamentary/appendix-to-the-journals-of-the-house-of-representatives

New Zealand Journal of Agriculture, 1920-1939. Available at: https://paperspast.natlib.govt.nz/periodicals/new-zealand-journal-of-agriculture

Nightingale, T. White Collars and Gumboots: A History of the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, 1892-1992. (Palmerston North: The Dunmore Press, 1992)

Noxious Weeds Act, 1900 (64 VICT 1900 No 10), 1900.

Noxious Weeds Amendment Act, 1921 (12 GEO V 1921 No 4), 1921.

Orchard and Garden Diseases Act 1928 (19 GEO V 1928 No 4), 1928.

Royal Horticultural Society. ‘Fireblight / RHS’. Accessed 30 April 2025. https://www.rhs.org.uk/disease/fireblight.

Star (Christchurch). ‘Fireblight Bad in Wairarapa’. 14 February 1929.

Strouts, R G. ‘Arboricultural Research Notice: Fireblight of Ornamental Trees and Shrubs’, 1996. https://www.trees.org.uk/Trees.org.uk/files/36/36a5ed0b-afed-4709-92cc-21b604121130.pdf.

Ward, G. Early Fruitgrowing in Canterbury New Zealand. (Christchurch: The Spotted Shag Press, 1995)

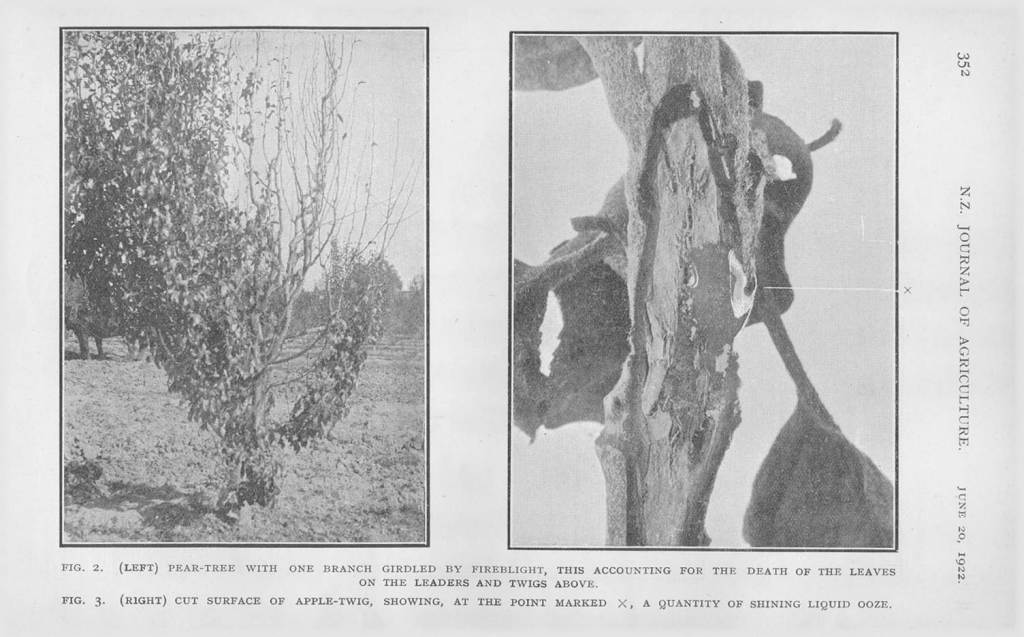

Waters, R. ‘Fireblight: Incidence of the Disease in New Zealand’. New Zealand Journal of Agriculture 24, no. 6 (1922).

Cover Image: ‘NZJA Dec 1912’: ‘Blossoms in Well-Kept Domestic Orchard: Orchard Work for January’. New Zealand Journal of Agriculture V, no. 6 (December 1912): 651.

Discover more from Cider Review

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A superb introduction to this topic, Kathryn. Thank you for taking the time to write this article and share it on Cider Review! I’m very grateful for your perspective and suggestion on how UK growers can look forward to the future and try to work towards a more holistic and inclusive fireblight response.

The response in New Zealand is truly remarkable, and could not be further away from what is happening in British pomology today. But hopefully over time we will be able to achieve something similar through a grassroots effort that doesn’t rely on government involvement to get established.

From our own experience on the farm, these varieties I would suggest people avoid planting if they have fireblight concerns: Blakeney Red, Gin Pear, Bartestree Squash, Moorcroft, White Bache, Oldfield, Green Horse, Turner’s Barn.

These pears I would endorse planting: Hendre Huffcap, Hellen’s Early, Yellow Huffcap, Red Pear, Thorn.

More research and evidence is needed to go beyond that short list! I wonder if any of the DNA sequencing of these varieties has identified a ‘fireblight resistance’ gene? We know Old Home is resistant but I am unaware personally of any published / accessible research that talks about this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Albert! Likewise, I very much hope there can be some kind of fireblight ‘network’ among growers in the UK. Even just establishing a clear and accessible bank of knowledge about the disease in the British context would be a start.

While I was conducting research for my PhD, I was fortunate enough to visit the Khan lab at Cornell University who are doing some excellent research into genetic resistance and/or susceptibility to fireblight. Back in 2021 they were able to confirm that there was a difference in the expression of genes between susceptible and resistant varieties. At the time, they were unable to say what exactly the function of these genes were, but I’m hoping it’s something they’ve been able to build upon!

LikeLike

Thank you Kathryn for this fascinating article! Here in New England fireblight is a huge problem for cider growers that seems to be getting worse as our local climate is becoming warmer and wetter during bloom time. I am reading this article on a rainy morning during peak bloom but with temperature around 50 Fahrenheit, thankfully too cool for the erwinia bacterium to reproduce. As Albert notes, we need more research on resistant varieties and rootstocks as well as alternatives to streptomycin. In a few days I will start inspecting each of our 2000 or so apple trees for fireblight strikes and hope that I can prune them out before it spreads. Until then, while the trees are still in bloom, I will be obsessively looking at weather reports and checking our online fireblight prediction tools every few hours to decide whether and what to spray.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment and for sharing your experience, Steve! If there’s one thing I’ve learnt about fireblight over the past few years, it’s how much time, effort, and mental energy goes into mitigating the damage it can cause. Scientific research may not be able to give us a ‘silver bullet’ for dealing with the disease, but hopefully the cumulative development of increasingly resistant rootstock and varieties, more knowledge sharing, and continuing spraying experiments can bring us incrementally closer to a positive outcome.

LikeLike