The world of cider and perry captures a diverse slice of horticultural and human history. An enquiring drinker can access a wealth of stories rising from the traditions that have grown up around the annual cycle of orchards, fruit and fermentation, potentially with a lengthy final act in a cellar. I want to shine a light, however, on the underappreciated story behind the first spring blossoms, the richness of the summer harvest, and winter transformation of fresh juice by yeast. The tales of toil, time and terroir within every bottle can be augmented by exploring the deep evolutionary history behind their existence.

I will trace cider and perry’s biological origins from two angles. The first is the scant fossil record of pome fruits, pomes being the type of edible structure that apples and pears are classified as. The second is etched in the genomes and geography of their living species. I refer to several geological intervals throughout the article. These appear in chronological order with dates given alongside to aid those few unreasonable readers who have not memorised all 101 stages of the geological timescale. We also need a few botanical names to help scaffold the story. Domestic apples (Malus domestica), pears (Pyrus communis), quinces (Cydonia oblonga) and their wild relatives form the pome fruit subtribe, the Malinae. Add in a few other plants which confusingly are not apples, and we get the apple tribe, the Maleae. Cast the net around a wider swathe of edible and ornamental flowering plants and we reach the rose family, the Rosaceae. Finally, the Rosaceae plus all other flowering plants comprise the angiosperms. This is where we will begin.

Deep Roots

Spin the clock back 120 million years to the early Cretaceous and the continents were barely taking on their modern divisions. Buoyant, rifting ocean crust spilled the seas thousands of miles inland. The poles were ice-free and occupied by rainforests and dinosaurs. Earth was a greenhouse planet, a far cry from the temperate, seasonal conditions which apples and pears thrive under. This remote time might seem an overreach when pome fruits are younger by over 100 million years. The Cretaceous, however, oversaw a watershed evolutionary event that would shape virtually all terrestrial ecosystems to come, including orchards: the Angiosperm Terrestrial Revolution.

Through chance reproductive error, diminutive early angiosperms duplicated their entire genome, leaving them with a redundant copy. They used these spare genes to transform their metabolisms and develop the first flowers and fruits, altering everything from planetary soil chemistry to the lives of the animals and fungi around them. Pacts of pollination with insects fuelled explosions of biodiversity in the undergrowth. New ecological opportunities rippled through Cretaceous food webs for the ancestors of modern mammals and birds. The burgeoning relationship between angiosperms and animals was occasionally a double-edged sword. The latter could as easily eat the former as to help them reproduce, resulting in (literally) bitter chemical warfare. Other suites of genes freed up by whole genome duplication were used to synthesise an arsenal of unpalatable phenolic compounds to deter erstwhile grazers. Perversely, many are now prized in our diets, from the alkaloids in coffee and chocolate to capsaicins in chilli peppers, as well as the tannins of tea and pome fruits. The chemical defences evolved during the Angiosperm Terrestrial Revolution are responsible for the balance and complexity prized in cider and perry, while orchard blossoms and their pollinators are similarly rooted in this turning point in Earth’s history.

Tellingly, the genes for alcoholic fermentation in yeasts also originated during the Angiosperm Terrestrial Revolution. Fermentation in general does not require oxygen but yeasts will happily continue to perform alcoholic fermentation under oxygenated conditions when they could instead respire, a much more metabolically efficient option. Natural selection generally weeds out inefficiency with zeal. The drawbacks of alcoholic fermentation, however, are offset by ethanol’s toxicity, enabling yeasts to rapidly exclude their teetotal competitors from a sugary buffet. Crucially, this only occurs when sugar is readily available. At low concentrations, they fall back to respiration. The evolution of sugar-rich fruits and nectar provided the right ecological conditions for yeasts to develop alcoholic fermentation, microbiology indispensable to all cider makers.

The First Orchards

Following the Angiosperm Terrestrial Revolution, the rose family split off from other flowering plants around 100 million years ago, followed by the apple tribe about 40 million years later. Despite the name, the group encompasses a wider range of plants that still crop up in the cider world, from hawthorn and rowan (carriers of fireblight) to medlar and serviceberries (sometimes added to Apfelwein to increase its tannic profile). Dated to 60 to 65 million years ago, their origin shortly followed the extinction that terminated the Cretaceous, resetting Earth’s evolutionary stage for new groups to rise to prominence.

The fossil record is a late memo of the divergences inferred from genomes but gives a glimpse into the environments that first shaped the apple tribe. In the early Eocene around 50 million years ago, India and Africa had yet to collide with Europe and Central Asia, themselves bisected by seaways of the Tethys Ocean. The Andes were rolling foothills and Antarctica covered by vegetation. Global climates were still hot, but even modest mountain ranges created naturally cooler conditions in a few places. Today, the orchards and cideries of the Western Cape in South Africa owe their existence in part to high elevations providing enough winter chill for apples to thrive. Correspondingly, the oldest fossil traces of the apple tribe have been found in the cool, mountainous conifer forests of the palaeo-Okanagan highlands in future Washington and British Columbia. Further gene duplications enabled the apple tribe to successfully adapt to the montane environment. Redundant genes found use not only in fruit development, but also for adaptations to the temperate climates which apples and pears thrive under today. While cider culture originated in Europe, the evolutionary roots of its raw materials may well be American. Today, the network of orchards and cideries across Washington and British Columbia are natural heirs to the legacy of the palaeo-Okanagan orchards.

The balmy climates of the early Eocene were ended by tectonic events half a world away. India finally collided with Eurasia, thrusting the Himalayas skywards. Billions of tonnes of rock eroding from their escarpments stripped carbon dioxide from the atmosphere while the final land bridges connecting South America with Antarctica were severed. Ocean currents looping around the pole cut off southward heat transfer. Ice crept across Antarctica, reflecting ever more sunlight away from the planet and causing global temperatures to plummet. Unperturbed, the apple tribe met the changing climate with enthusiasm, undergoing a phase of rapid, intense diversification through the late Eocene to the Oligocene thanks to their temperate adaptations.

Pome fruits finally made their appearance within this wave of new diversity. Lahars and ashfalls spreading from the Thirtynine Mile volcanoes of southern Colorado 34 million years ago entombed the region’s flora and fauna in muddy lake beds, forming the rocks of the Florissant Formation. This botanical Pompeii exquisitely preserves leaves with a distinct resemblance to living apple species, alongside a cornucopia of fossilised flowers and even fruits from other members of the apple tribe.

Producing Pomes

Despite palaeontologists’ best efforts, nothing has been found at Florissant which resembles an apple or pear. The ancestors of modern orchard species had yet to develop large, fleshy fruits or tree-like forms. Instead, they were probably shrub-like with small clusters of fruits more akin to berries. So, what led to the evolution of large pomes, the essential raw materials of cider and perry? Based on the geological time spans separating small and large fruits across species of the apple tribe, the latter probably evolved independently in apples, pears and quince during the mid Miocene, 14 to 18 million years ago. This gives the geological context needed to pick apart their origin.

At the beginning of the Miocene, the Turgai Straits, a narrow seaway connecting the warm, tropical waters of the Indian Ocean to the Arctic Circle across Central Asia, was reclaimed by dry land. Colder, dryer conditions forcibly separated West Eurasian and East Asian plant populations, a divide etched in the genomes of living pear species, but the apple tribe continued to thrive as climate change swept across Eurasia. Small mammals and birds were still efficient at dispersing their small, berry-like pomes as forest habitats evolved with the changing climate. The problem came when these forests began to shrink and fragment in the face of expanding grasslands. Small mammals and birds were poorly suited to crossing open grassland, nor did their larger native bovids present a viable alternative. Sugar-rich fruits disagree with ruminant digestive systems, and they do not tend to consume pomes in appreciable quantities. Apples and pears were trapped at the margins of dwindling forest patches, putting them at ever greater risk of extinction.

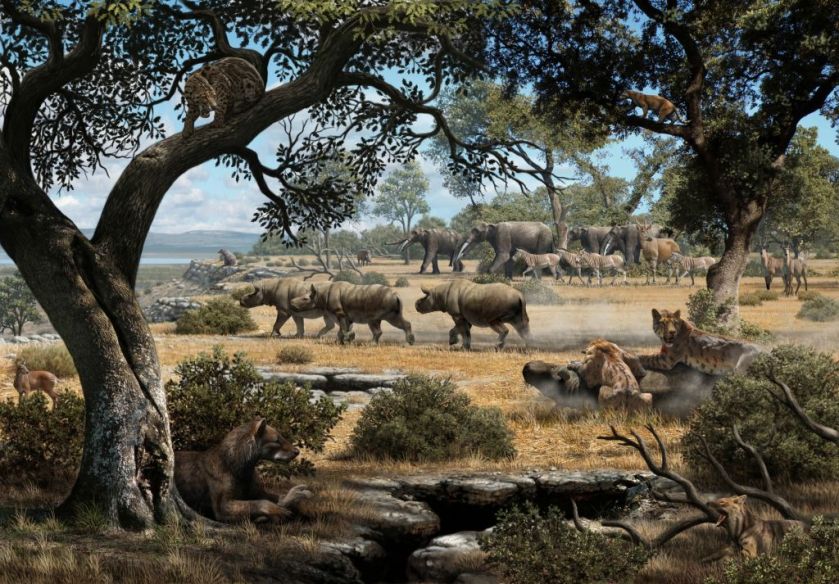

The conundrum was solved by the collision of Africa with Europe in the mid Miocene. Elephants, apes and rhinoceroses crossed the newly formed land bridge into Europe, ranging widely between forest patches and happily browsing on fruits. The largest species even cleared away smaller saplings and shrubs during their foraging, engineering forest ecosystems to the advantage of the apple tribe by creating new space for growth. Pome fruits were not the only group that took the opportunity provided by the immigrant African mammals. Stone fruits also became large and enticing enough to capture their attention, with pips and pits alike hitchhiking to new forest patches in their guts.

Large fruits were metabolically expensive to produce and fuelling these extravagant structures required far more water, nutrients and sunlight than shrub-like forms could supply. Only trees could support such demands. After millions of years in the undergrowth, the first truly recognisable orchards slowly spread across Eurasia. Apes, part of the exodus across the land bridge, soon came to enjoy their fruits, marking the first contact between pomes and our hominoid forebears. Compared to the broad, flat crushing molars of their African ancestors, the teeth of Eurasian hominoids showed clear signs of adaptation towards softer, juicer sources of plant matter. During their foraging, they would have encountered the odd piece of rotten, naturally fermenting pome fruit. Such low-intervention cider or perry, produced by the unbridled actions of wild yeasts on a Miocene orchard floor, would have been on the funkier side.

Some biologists have even hypothesised that our predilection for alcohol has an evolutionary purpose. Natural fermentation is a sure indicator of ripeness, making ethanol a tangible tip-off for a rich source of sugar, with the trade-off of moderate to severe alcohol poisoning. Around 10 million years ago, however, mutations in the hominid line substantially upregulated their tolerance, setting the foundations for my ability to keep writing this article after a generous helping of Oliver’s Yarlington Mill.

A Tale of Ice and Cider

Hybridisation has been the pome fruits’ key to success. Within species, it maintains their genetic diversity, generating both immense adaptability and delicious new varieties. Millions of years of hybridisation between species, however, has transformed a neat family tree into a tangled hedge. It is challenging to trace the final steps leading from the first large-fruiting pomes to their domesticated descendants, but their genomes still offer some useful clues.

At the start of the Pleistocene, 2.6 million years ago, the Earth tipped into an ice age. Grasslands and forests across Eurasia and North America were fragmented as glaciers and tundra stole southwards. Slow-adapting animals and plants became trapped in isolated valleys with rare mild climates. Over tens of thousands of years, the glaciers waxed and waned with Earth’s wobbling orbit. The inhabitants of glacial refugia were periodically released, allowing them to interbreed with other populations. This has left characteristic signatures of high genetic diversity in their modern wild populations that match the locations of these ancient refugia, including in the apple tribe.

One ex-refugium in the foothills of the Tien Shan mountains of Central Asia is still home to Malus sieversii, the wild ancestor of the domestic apple. M. sieversii has recently found its way into fermentation tanks through the work of Apple City Cider in Almaty, Kazakhstan. The relationship between humans and prehistoric apples, however, is demonstrably older. Around 200,000 to 240,000 years ago, a series of hot springs in what would become Ehringsdorf in central Germany petrified a trove of fossil apples alongside stone tools and bones of Neanderthals. Preserved as impressions in travertine with signature rings of five pips at their cores, it is impossible to say that they had been intentionally gathered. Regardless, Neanderthals must certainly have encountered these wild apples, some of which may even have begun to naturally ferment.

When the ice retreated around 10,000 years ago, ushering in the interglacial containing all human civilisation, the large mammals which had dispersed pome fruits across the continents were all but gone. It fell to humans to pick up that torch. Over the millennia, seeds of M. sieversii made their way down from the Tien Shan mountains along the Silk Road, with hybridisation with European and Asian crab apples creating the domestic apple on route. Pears present a slightly different story. Once thought to have been domesticated in Western China, more recent genetic evidence suggests that there was a second, independent centre of domestication in Europe. The Silk Road again facilitated dispersal of domesticated pears in both directions over the last few thousand years of human history. Continued hybridisation with the wild European species M. sylvestris and P. pyraster are respective origins of the more tannic cider apples and perry pears traditionally used in Britain and France.

Ferments of Futures Past

Domesticated apples and pears capture a rich swathe of evolutionary history, but they are not the only options in the world of cider. Some of the most exciting advances in my opinion come not just from new techniques, but from alternative branches of the pome fruit family tree which capture that wider history. I have already touched on the work of Apple City Cider, but rosé ciders also owe their existence to crossbreeding with a wild Central Asian cousin, the naturally red-fleshed M. niedzwetzkyana. In cideries across the US, crab apples are another departure from pomological tradition that enters seldom explored evolutionary territory. The Dolgo crab is step away in time again from M. sieversii. Some cideries have gone further still, using apple species native to the US and separated not by thousands, but millions of years. The same goes for perry, thanks to a few makers who have experimented with the Nashi pear, P. pyrifolia.

Beyond apples and pears, we still welcome the pomes of quince and medlar within the wider bracket of the cider world. Whether as co-ferments or in full juice forms, Cydonia and Mespilus take us to new evolutionary pastures (or rather orchards), although they are less forthcoming with their backstories. They comprise single species in stark contrast to apples and pears, largely closing the door to comparative genetics, but they were probably both domesticated in the Middle East or the Caucasus.

There is also a final part of the pome fruit evolutionary landscape that cider makers have yet to explore. The loquat (Eriobotrya japonica), despite the common name of Chinese or Japanese plum, is the earliest diverging member of the pome fruit subtribe that produces large fruits. Unlike its cousins, it is an evergreen species adapted to tropical climates, but its fruits are no less fermentable. It is perhaps the last major botanical outpost for cider makers to explore. Some might argue that loquats are too far removed from temperate orchard fruits to consider, but they are undeniably pomes. Do it, puritan!

Spanning evolutionary, climatic and continental upheaval from the Cretaceous to the present, the biological backstory of pome fruits is remarkable. Uncertainty will always surround parts of the story. Genomic family trees are ultimately calibrated against the geological record and so any palaeontological account is sensitive to new fossil evidence. I have also made a few well-informed decisions here and there to present a coherent narrative and avoid becoming mired in technical quagmires or controversy. Even if the story shifts under the weight of future discoveries, my hope is that a drinker can still reflect on the deep history underlying their cider and perry. A bottle, cask or keg does not just reflect the terroir of the fruit (geologically fascinating in its own right) or the time and toil of the maker. It contains the product of over 100 million years of evolutionary innovation.

For the fact-checkers and irreparably curious

Abdollahi (2019). A review on history, domestication and germplasm collections of quince (Cydonia oblonga Mill.) in the world. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution, 66: 1041-1058

Benton et al. (2009). The Angiosperm Terrestrial Revolution and the origins of modern biodiversity. New Phytologist, 233: 2017-2035

Carrigan et al. (2014). Hominids adapted to metabolize ethanol long before human-directed fermentation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA, 112: 458-463

Dashiko et al. (2014). Why, when, and how did yeast evolve alcoholic fermentation? FEMS Yeast Research, 14: 826-832

DeVore and Pigg (2007). A brief review of the fossil history of the family Rosaceae with a focus on the Eocene Okanogan Highlands of eastern Washington State, USA, and British Columbia, Canada. Plant Systematics and Evolution, 266: 45-57

DeVore and Pigg (2013). Paleobotanical evidence for the origins of temperate hardwoods. International Journal of Plant Sciences, 174: 592-601

Jin et al. (2024). Unravelling the Web of Life: Incomplete lineage sorting and hybridization as primary mechanisms over polyploidization in the evolutionary dynamics of pear species. Preprint on bioRxiv

Korotkova et al. (2017). Towards resolving the evolutionary history of Caucasian pears (Pyrus, Rosaceae) – Phylogenetic relationships, divergence times and leaf trait evolution. Journal of Systematics and Evolution, 56: 35-47

Liu et al. (2022). Phylogenomic analyses in the apple genus Malus s.l. reveal widespread hybridization and allopolyploidy driving the diversifications, with insights into the complex biogeographic history in the Northern Hemisphere. Journal of Integrative Plant Biology, 64: 1020-1043

Spengler (2019). Origins of the apple: the role of megafaunal mutualism in the domestication of Malus and rosaceous trees. Frontiers in Plant Science, 10: 617

Spengler et al. (2023). Bearing fruit: Miocene apes and rosaceous fruit evolution. Biological Theory, 18: 134-151

Velasco et al. (2010). The genome of the domesticated apple (Malus × domestica Borkh.). Nature Genetics, 42: 833-841

Wang et al. (2009). Rosid radiation and the rapid rise of angiosperm-dominated forests. PNAS, 106: 3853-3858

Wu et al. (2018). Diversification and independent domestication of Asian and European pears. Genome Biology: 19, 77

Xiang et al. (2016). Evolution of Rosaceae fruit types based on nuclear phylogeny in the context of geological times and genome duplication. Molecular Biology and Evolution, 34: 262-281

Zhang et al. (2017). Diversification of Rosaceae since the Late Cretaceous based on plastid phylogenomics. New Phytologist, 214: 1355-1367

Zhang et al. (2021). Phylogenetic patterns suggest frequent multiple origins of secondary metabolites across the seed-plant ‘tree of life’. National Science Review, 8: nwaa105

Zhang et al. (2023). Phylogenomics insights into gene evolution, rapid species diversification, and morphological innovation of the apple tribe (Maleae, Rosaceae). New Phytologist, 240: 2102-2120

Zheng et al. (2014). Phylogeny and evolutionary histories of Pyrus L. revealed by phylogenetic trees and networks based on data from multiple DNA sequences. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution, 80: 54-65

Discover more from Cider Review

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A fantastic debut! Really enjoyed reading this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Your tannin article was absolutely the motivator that got me thinking about how I could cross my palaeontological and pomological interests, hats off to you!

LikeLike

What a great read Joe and i love the combination of fact and a little imagination to weave the storyline together. Much that i did not know. Thanks.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cheers Tom! Really glad you enjoyed the read, it was great fun to put it all together

LikeLike

Really enjoyed this! And an addendum on the “alternative branches” idea you were mentioning: there are some passionate advocates for p. calleryana seedlings and intentional hybrids here in the States. Though they get a bad rap as an ecological invasive, larger-fruiting varieties (either spontaneous or intentional hybrids with domesticated pears) often have high sugar, tannin, and disease resistance. Plus, if we can breed toward larger fruit, it’ll slow the bird dispersal that makes callery such a menace! Thanks for the trip to deeper history

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cheers Matt! I hadn’t come across P. calleryana – following up on this was really interesting

LikeLike

Brilliant work. Really opened up thoughts which had been percolating without evidence. Fantastic bibliography too – thank you. Really looking forward to what’s next! Could you unwrap a little piece on soils and fruits? Absolutely love the colossal time frames you work with.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m really keen to take a closer look at the role of geology in cider terroir! Will definitely look into what I could draw together

LikeLike

Joe, that was a fascinating read and a great history lesson. I think I will look at my orchards differently now!

LikeLike

Pingback: Pigs, Pomona & Provenance: – Fine Cider & New British Charcuterie | Cider Review