’I can’t go up to the orchard at the moment,’ Lydia Crimp of Herefordshire’s Artistraw Cider tells me. ‘The grass is too long – it sets off my hay fever. Tom has to go and look after it.’

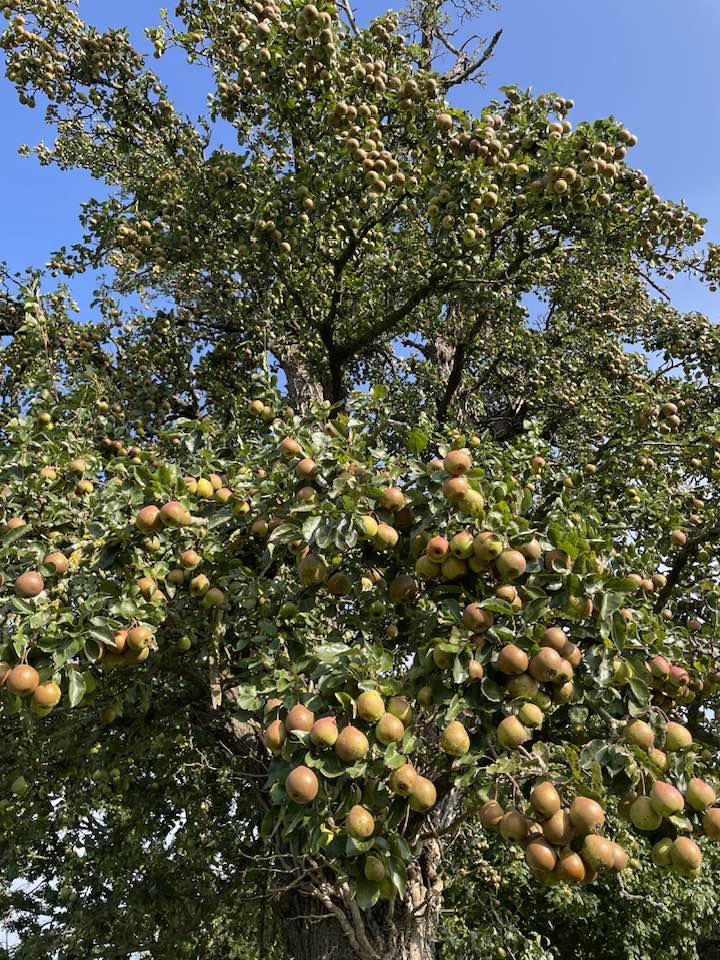

Not being sufferers ourselves, Caroline and I dandle up the orchard’s steep slope, pushing through the thigh-high grass that leg-warms the still-young, spindly trees. A plaque in front of one of them proclaims it to be the Holmer Pear, planted by Paul Stevens as part of his project to restore this rare variety. I can’t recognise the others, not being a pomologist, but I know them to be a polyculture of old, rare and treasured Herefordshire varieties. Together they stitch a tapestry of centuries of orcharding and cidermaking heritage; a defiant bastion against something that is fading away. As I tread amongst it, I see that, within the feather-tufted grass that had looked so homogenous from the bottom of the hill, are a thousand different plants, unique as snowflakes. Leaves and herbs and flowers and burrowing weeds; a teeming ankle-tall jungle of life.

***

I have this theory that people don’t think about orchards, not really. They haven’t had the chance to. To wander deliberate forests of fruit trees, see acreage of blossom erupt in a pink-white hallelujah, find themselves in a heaving, beaming, festooning technicolour avenue of unnumbered baubling apples.

I know I didn’t think of orchards for the first 25 years of my life. I knew about apples of course, I drank cider at the pub, but orchards – didn’t spare them a thought.

If I did, it was in an almost unreal sense. Like something that seems almost too fantastical to exist in real life. Orchards are the set stages for myths and legends; the garden of Eden, the garden of the Hesperides. They don’t feel like agriculture, perhaps, to most of us; certainly not in the same sense as the fields of wheat and barley that any two-minute drive out of a city will take you past. Not even in the same sense as vineyards, plastered across the labels of so many wine bottles and so many travel guides to so many countries. Orchards are something apart. Most of us have never seen one, and so despite the centrality of the apple to so much of life – ‘an apple a day’, ‘the big apple, ‘apple of your eye’, ‘Adam’s apple’ – they rarely trouble the fringes of our consciousness.

Towards the end of April they gained a minute in the national spotlight for entirely the wrong reason. Heineken, by far the biggest cidermaker in the world, largely through its Bulmers brand, cut down a 300-acre orchard in Monmouthshire, not far from the long grass of Artistraw’s Bryntirion hill. ‘National outcry’ would be overdoing it. There was a brief squeak of protest after which, besides this excellent article from James and another from Laura Hadland, the rest was silence – perhaps accompanied by the resigned shrug of ‘nothing we can do, is there?’

Heineken themselves stated that the loss of the orchard was not only inevitable, but the fault of changing consumer tastes and a drop in the amount of cider being consumed in the UK. This was corroborated by the National Association of Cider Makers, who suggested that ‘the amount of cider being consumed in Britain had dropped by a third in the last decade’, leading to the ‘devastating loss’ (their words) of 2000 acres of British cider apple orchards in the last few years.

2000 acres. Let’s unpack that. 300 acres was described, in the aftermath of the Heineken orchard’s felling, as ‘140 football pitches’. So, scaled up to 2000 acres, that’s 932. These may have been bush-trained orchards, planted at fairly high densities, possibly with some lower-density, traditionally-spaced orchards. Opinions on exactly what that constitutes in numbers of trees varied wildly between the websites I looked at; anything from 100 (in the widest-spaced traditional orchard) to 370 an acre. Even taking the lowest estimate, that’s hundreds of thousands of trees removed in less than a decade. Assuming a higher rate of planting, the figure could be around or over half a million.

There was some commentary, in the wake of the orchard’s felling, that it was an intensively-farmed orchard subject to various chemical sprays and which certainly wasn’t employing any sort of regenerative practices. Commentary on farming methods is outside the scope of this article; I’ll simply add that orchards farmed through any method are not only amongst the best forms of agriculture for carbon capturing (James, as ever, is better on this than me), but form flightpaths for birds and homes for huge quantities of wildlife – to say nothing of the restorative green spaces they provide to people. In short: we were better off with those 2000 acres than we are without them.

What is cider made of?

All of the corporate language around the destruction of these orchards centred on a lament for the falling market. If only people in the UK were drinking more cider, all this could have been spared.

It’s certainly true that, volume-wise, there has been a dip in cider sales since the years immediately following ‘the Magners effect’ of circa 2007, when cider briefly became, if not ‘cool’, then more noticed than it had been previously. This article, in which Carlsberg entertainingly pitch Somersby as a riposte to ‘artificial tasting mainstream ciders’ cites 911 million litres drunk in 2011 in the UK, the NACM’s 2013 report cites ‘1.5 billion pints’ (about 850 million litres) whilst the latest Weston’s report mentions 695 million litres drunk in total through 2023. So, certainly an alarming dip, if not quite the ‘third’ suggested by the NACM.

As an aside, this dip in volume isn’t reflected in value. In 2011 the UK market was worth £2.867 billion. In 2023 it was worth £3.06 billion. Not the increase that the largest companies would be after, especially when adjusted for inflation, but certainly not the precipitous collapse that the drop in consumption would suggest.

What can we infer from this? Again, we turn to the Weston’s Report, where there is a clue in the form of the significant rise in popularity of ‘crafted cider’. Readers of this website will probably understand why I find their annual definition of ‘crafted’ to be eyebrow-raising; the top five brands are, from first to fifth, Weston’s Vintage, Thatchers Somerset Haze, Thatchers Blood Orange, Thatchers Katy and Aspall Premier Cru. Indeed Thatchers, Weston’s and Aspall account for the entirety of the top 10 brands listed. Nevertheless, their 10 ‘crafted’ brands point to consumers being prepared to pay more for at least a higher perception of quality. And perhaps tellingly, Heineken, whose bestselling cider, Strongbow, remains the UK and the world’s number one, doesn’t feature on the list at all.

‘Crafted’, as proven by the ciders on Weston’s list, is a near-impossible term to define, but the implication is unquestionably that the respective drink is of higher than average quality. That better than average ingredients have been used, and more painstaking than average methods and care employed. We will all have our own feelings on what this means, but in cider terms, ‘better ingredients’ indisputably starts with a higher quantity of fresh-pressed apple juice.

Which brings us to the first of our elephants in the room: juice content.

It is notorious in cider circles – but virtually unknown outside of them – that the British government defines cider in law (through Excise Notice 162) as ‘a product which is obtained from the fermented juice of apples’, but for which ‘juice content requirements are satisfied if… a qualifying fruit juice comprises at least 35% of the volume of the pre-fermentation mixture for the product.’

In non-legalese, this means that cider can be made from just 35% apple juice. And all of that apple juice can be from concentrate, rather than being freshly pressed from apples.

Indeed there’s a kicker within that second sentence. Because Excise Notice 162 further stipulates that juice content requirements are satisfied if:

‘The total of:

(i) the volume of qualifying fruit juice included in the pre-fermentation mixture, and

(ii) the volume of qualifying fruit juice added after fermentation begins, comprises at least 35% of the end product.

(2) ‘Qualifying fruit juice’ means apple or pear juice of a gravity of at least 1033 degrees.

(4) ‘Pre-fermentation mixture’ means the mixture of juice and other ingredients in which the fermentation (from which the cider is obtained) takes place, as that mixture exists immediately before the fermentation process begins.’

In other words, as long as the ‘pre-fermentation mixture’ is an apple juice (or apple juice from concentrate) of at least 1.033 gravity, you’re good to go. But there’s a loophole here.

A gravity of 1.033 is, in terms of the sugar ripeness of apples, unbelievably low. Even in a poor vintage, the majority of apples – and certainly the majority of western England cider apples, will achieve meaningfully higher sugar ripeness than that. In 2022, Ross-on-Wye reported a gravity of 1.068 in their Foxwhelp, by no means the highest-sugar variety. 1.033, fully fermented, is around 4% abv. It would be unusual for a fully-ripe apple of almost any sort, grown in almost any vintage or climate, to come in much under 5% if fermented to dryness.

So what has gone on here? Well, juice from concentrate is not solely apple juice. It is rehydrated apple juice. It begins as pressed apples and is dehydrated into a sort of syrup with a gravity far, far higher than that of fresh-pressed juice so that it can be transported in bulk and safely stored without risk of spoilage. This concentrate is then rehydrated with water into juice, such as you can buy in the supermarket.

Now, those original pressed apples may well have produced juice with a gravity some way under 1.068. But it is incredibly unlikely that it was as low as 1.033. Which means that companies can add back more water than they took out, and still hit the legal stipulations to claim that their cider contains ‘35% juice’. It’s likely that many of the companies fulfilling the government-set conditions are using just 25% or less.

No wonder they don’t need that many orchards to hit their numbers. But it’s not just about how many orchards are needed – it’s also where those orchards are.

The big red herring

Even allowing for low juice content, concentrates and a reduction in consumption, the quantity of cider made in the UK is vast. The Weston’s Report cites a market volume of more than double the second largest, South Africa. Virtually all of that consists of British-made cider, and that level of production takes a lot of apples.

What’s more, the story of plummeting demand becomes something of a head-scratcher when considering the Weston’s Report in more detail. Heineken, already boasting the largest market share by a vast distance, is shown to have grown by 6.4% in the last year. Apple cider, as opposed to fruit cider, ‘continues to dominate’ on-trade sales, and although Heineken’s off-trade sale have fallen slightly (other companies have fallen by larger amounts, though some, like Thatchers, have experienced remarkable growth) their leading brand, Strongbow, continues to tack (modestly) upwards.

And there is a red herring here. Remember, many of these companies – and Heineken perhaps most obviously – are not confined to the UK. They are multinationals; whilst the British market might be important, it is only one of many. In Heineken’s case it isn’t even their home. You can buy Strongbow in the USA, South Africa, Australia, Taiwan, Uganda, the UAE – really anywhere Heineken can reach, which is virtually everywhere.

And whatever the volume struggles might be in the UK, on a global level cider is booming. According to one report, in the next ten years it is projected to grow from 7 billion to 11.4 billion dollars. Heineken themselves reported ‘the strong growth of Strongbow in South Africa’ in their 2022 report, and followed that by purchasing one of their largest cider competitors, Distell, in 2023, growing their total volume from 5 million to 7 million hectolitres. It seems certain that Strongbow, the leading British cider brand, will soon be available in even more countries, with even more demand, than has previously been the case. Suddenly cutting down all those orchards of cider apples seems a little reckless?

Back at Artistraw, Lydia tells me of an email she recently received. It was from a company in Türkiye, wondering whether Tom and Lydia would be interested in buying any concentrate from them.

I found this both absolutely hilarious and more than a little scary. Tom and Lydia are two of the most determinedly natural cidermakers anywhere in the world. They don’t even add sulphites to their perry these days; nothing is added, nothing taken away. A less likely customer for apple concentrate you are unlikely to find. And yet this company in Türkiye felt it was still worth an approach – which tells us a lot about the custom they expect from makers in the UK.

There is no law whatsoever that says that British cider should be made from British apples. And there certainly isn’t a law that requires makers to disclose where their apples come from. Companies realise that British drinkers would prefer to think of their cider as having been made from British apples – and indeed that, when drinking British cider, international drinkers would prefer to think of it as having been made from British produce – and so they use deceitful verbal tricks like ‘made from British apples’, when such fruit only represents a small portion of the total.

But, though British apples are almost disgracefully cheap – £250 a tonne for the very best, hand-picked fruit (which is certainly not what the biggest companies use – this figure represents less than 0.1% of apples bought for cider in the UK) vs a starting point of around £1500 a tonne for British wine grapes according to Henry Jefferys’ Vines in a Cold Climate – far cheaper still is to tanker in concentrate from one of the behemoths of apple growing around the world.

According to this chart, published this year, the top four producers of apples – by far – are China, Türkiye, the USA and Poland. The UK doesn’t even make the top 10, lagging far behind even European countries like Poland, Italy and France. Simply put, there are more apples to be had, and at a lower cost, by looking elsewhere. Not least when a global product like Strongbow can legally be produced in any country in the world. In some countries like the USA, where the minimum juice content law stipulates at least 50%, it isn’t even the same recipe. Strongbow’s own website cites made ‘in the UK’, but it only takes a quick google to find Heineken themselves attesting to it being made all over the world.

Apple concentrate, made from whatever the cheapest apple varieties are and wherever they’re grown, homogenised with processes like chaptalisation as well as artificial adjustments to acidity, sweetness, aroma and strength, make things far cheaper than only using fresh-pressed juice, or even only using juice concentrate made with apples from a single country.

And cost, of course, is key. Not least since (Weston’s Report again) off-trade sales in the ‘Big Four’ supermarkets alone (Tesco, Asda, Sainsbury’s Morrisons) account for 60% of all UK cider sales full stop. Their aggression when it comes to margins, given their lack of retail competition in the UK, is notorious; an 18-pack of Strongbow at Tesco works out at £1.77 a litre (please don’t consider that link an endorsement…). Companies like Heineken are motivated solely by profit; it’s naive to expect them to act based on any other interest. When their biggest UK customers are charging those sorts of prices, ingredient cost management becomes ruthless.

But hang on. Isn’t there a non-negotiable here? Multinational or not, macro cider or not, isn’t the character of western British cider advertised as and dependent on the character of so-called ‘cider apples’; bittersweet and bittersharp apples, containing textural qualities of tannin that contribute so much to mouthfeel and body? Quoting Strongbow’s own web copy: ‘It’s the blend of the bittersweet cider apples, grown and pressed in Herefordshire, that gives Strongbow Original its unique thirst quenching taste.’

Britain may not rank terribly highly in the overall charts for global apple growth, but when it comes to bittersweets and bittersharps, we’re in a league of our own. Top of the table by miles, with France second and every other country virtually negligible. Strongbow’s advert released as recently as 2014 describes the cider as ‘bittersweet by nature.’ So, surely, the bittersweet apple orchards are at least safe up to a point?

Which brings us to another elephant in the room, and some interesting copy on the Strongbow website: ‘still brewed in the UK’. ‘Brewed’, is it? Something smells hoppy to me.

Lager made from apples

One of the first interviews I ever conducted in my cider writing was with industry legend Andrew Lea. He told me that his professional journey in cider began when he worked at the now-long-since-closed Long Ashton Research Station (LARS) in ‘the early ‘70s’ on a Bulmers-funded study into tannins. ‘They were worried that the business was growing so greatly that there wouldn’t be enough tannins around in the cider apples to satisfy demand.’

By the end of the decade the picture had shifted markedly. ‘The whole of the market shifted during the 70s and the need for high tannin disappeared,’ Andrew said. ‘The marketing people sort of shifted the idea of cider from something that was high-tannin to something closer to lager that was low in tannin.’

It won’t have escaped your notice that I’ve mentioned Heineken, a brewer, several times in this piece. They’ve owned Bulmers since 2008 when, jointly with Carlsberg, they bought Scottish & Newcastle (S&N), who themselves had bought Bulmers in 2003. Eight years before buying Bulmers, following their purchase of Courage, S&N had become the biggest brewers in the UK. (It certainly wasn’t the lure of Bulmers that tempted Heineken and Carlsberg.

The purchase of Bulmers by a brewer that already owned Courage completed a journey that Courage themselves had been instrumental in beginning over 40 years previously. Bulmers: A Century of Cidermaking by L.P. Wilkinson sheds fascinating light on this subject:

‘The three decades after 1945 saw the gradual absorption of most of the other cider-making companies into two large groups of brewers … Coates (1956), Gaymers and Whiteways (1961) were acquired by Showerings and renamed ‘Coates Gaymers’ and Showerings in turn were taken over by Allied Brewers (1968); and the Taunton Cider Co., having swallowed up some smaller cider companies, was eventually taken over by a consortium of breweries, largely at the instigation of Courage. This was later joined by Bass and other brewers and finally in 1971 Guinness also joined the consortium.’

Bulmers themselves were pursuing a strong policy of takeovers in the 1960s. Wilkinson writes: ‘in 1965 the firm bought all the issued share capital of the Tewkesbury Cider Co. Ltd, which gave it access to all the licensed properties of Ansell’s Brewery.’

It’s arguable that possibly the survival, and certainly the growth, of cider in the 1960s was dependent on consolidations and takeovers like these. Orchards were being lost to the mechanisation of agriculture – the same was true across all the cider and perry regions of Europe – and a movement to a more urban society necessitated an increased presence for cider in the brewery-owned pub chains in towns and cities across the UK.

But the influx of new cider brands on these brewery taps, and the requirement for a consistent product across a large number of pubs, together with the reduction in small farmhouse production and the consolidation of small brands within increasingly vast ones, meant that cider was under pressure to homogenise. What’s more, the majority of customers to whom it was presented and, tellingly, the majority of the people doing the presenting, were unfamiliar with western British cider, with the textures of tannins and the flavours of bittersweet apples. They certainly didn’t want a product that would change markedly on an annual basis, as vintage-centric full-juice cider inevitably does. The 1950s had seen the birth of TV advertising, hastening the need for brands to become nationally available and to appeal to a mass-market.

In short, the brewery owners of cider companies wanted something a bit more familiar. A bit more like beer. And in the 1970s, when these cideries had consolidated under larger breweries, the prevailing beer was rapidly becoming lager.

I was fascinated to learn from this Boak and Bailey piece that in 1960 lager accounted for less than one per cent of British beer, and that even in 1963 it wasn’t generally available on draught. By the mid seventies it accounted for over 20% of all beer sales and by the end of the 80s it had far outstripped sales of ale. Even beers outside the category were lightening and weakening – the very formation and development of CAMRA from 1971 onwards was to act as a bulwark against this increasing trend.

Bittersweet cider isn’t quite analogous with the cask ales that CAMRA was defending, but there are certain parallels. Both are textural – ‘bitterness’ features prominently in both categories – both are bolder and, generally, deeper in flavour than the lighter styles that were gaining prominence, and both accordingly tend to express themselves at their fullest at higher temperatures than was becoming the norm for the serving of drinks in pubs. (Whether that’s your preference is, of course, another matter and entirely up to you.) It’s perhaps no surprise that CAMRA themselves soon added the bittersweet and bittersharp styles of cider to the rostra of drinks they championed, with the formation of the Apple Committee in the 1980s.

Critically, the natural strength of dry bittersweet cider is, as we have seen, higher than that of lager – anywhere from around 6-8.5% abv. Naturally then, in order to serve them by the pint, as lagers were, rather than in smaller measures and different glassware, dilution became an encouraged necessity. Strongbow’s first adverts (well worth a watch) emphasise that the cider has ‘all the strength of the great draught ciders – in a bottle’ and show drinkers enjoying it in wine glasses as well as larger ones. By the time they reached me in the late noughties, the flavour emphasis had pivoted to ‘total first pint refreshment.’

There are many arguments to be had about ‘changing tastes’ and how they come about. Fashions, the introduction of new flavours, generational shifts all play their part. But there’s no question that changes in taste can be and are also heavily, heavily influenced by powerful brands and by what they wish to present to the market.

Macro cider’s two-faced approach of asserting the traditional bittersweet apples of western Britain, whilst diluting the quantities of bittersweet apples used is the direct result of an attempt to lagerify their ciders in both image and character. What’s more, the bittersweet apples predominantly used in macro cider today and extolled in the web copy and on the back labels of so many of the big brands are wholly different to those featured in the ciders of the 60s and 70s.

When Andrew Lea began his research at LARS, it was at the time of a Bulmers-led project to plant Dabinett and Bisquet (then mistakenly believed to be Michelin) apples across Herefordshire. Dabinett is a serious bittersweet. One of the fullest, juiciest, highest-sugar apples of all, and with significant quantities of tannin. Bisquet, whilst lighter (and chosen partially for its ability to pollinate Dabinett) still contains meaningful tannin.

Today those two apples remain in the top four varieties grown for cider in western England. The other two? Falstaff, a tannin-free apple bred in Kent, and Gilly, one of several apples bred in a programme begun by Liz Copas and Ray Williams at the Long Ashton Research Station in the 1980s to create an early-ripening bittersharp that could be used for cider. It is pleasant enough; light, fresh, with nibbly acidity and the mildest of tannins. But its widespread adoption marks a clear intention to change the overall flavour profile of western British cider.

It’s hard to overstate the impact that big breweries have had on the character of cider and the shape and quantity of orchards in Britain. That cider is near-ubiquitously viewed as something light and sweet with no detectable tannin, a higher level of acidity and a high degree of artificial carbonation – not to mention something described as ‘brewed’ by the biggest cidermaker in the world – is beer’s direct responsibility. Big beer has shaped everything from the glasses cider is drunk in to the apples it is made from, and in removing orchard and vintage from most of its presentation has enabled – and taken advantage of – higher levels of dilution and more forceful and impactful practices in the factory and laboratory.

The majority of cider made in this country is simply a small portfolio addition for far bigger multinational companies whose primary concern is other drinks, who aren’t really interested in cider beyond how they can market it most cost-effectively and whose interest in apple varieties begins and ends with how well they yield and whether they can be homogenised into something with mass-market appeal.

In 1960, when Strongbow was first fermented, Bulmers made both from-concentrate draught and full-juice, champagne-method pomagne by the tens of thousands of bottles. Today, for all the Weston’s Report’s talk of craft, there is barely a single full-juice, aspirational cider to be found across the portfolios of any of the largest cider brands, and none whatsoever in the Bulmers stable. One size has been made to fit all, with the only variable the particular species of fruit flavouring added to any given apple concentrate base. The lagerification of British cider has been remarkable in its ubiquity.

But devastated orchards are not a corporate issue. They are a political failure.

It is easy and indeed important to scrutinise and criticise the capitalist practices and cynicisms of multinationals. After all, whilst this article concerns environmental insouciance and (admittedly self-interested) lack of transparency and reduced character in production, they are hardly the worst things of which companies such as Heineken have been accused.

But demonisation of huge multinationals for making as much money as possible with as little cost as possible to themselves is utterly fruitless. As mentioned, these companies exist for the sole purpose of profit. Indeed they are responsible to vast numbers of shareholders for it. No one at Heineken is rubbing their hands and actively plotting the way to make the worst cider possible. After all, for them it isn’t actually about cider. It is solely about money.

If there was a way that saving more orchards, protecting and grafting the most flavoursome varieties and including a higher juice content in their products would result in a healthier bottom line for them than Strongbow does currently, Heineken would do it. The Monmouthshire orchard, as Gabe Cook pointed out in a video on his substack, belonged to them and it was therefore within their rights to chop it down. Clearly, they felt the company and its shareholders would be better off without it, and so it was removed – just like the orchards of many growers whose contracts were cancelled in the last decade.

Large companies can talk about how sorry they are at the loss of orchards. They can point to environmental initiatives. They can be railed against, they can even be subject to criticism and investigation by serious journalists and prominent broadsheets, as they were when the orchard came down. But as long as they are empowered to continue making products the way they currently are, with the transparency they currently offer, they will do so.

The key word there is ‘empowered’. And here we reach the biggest elephant in the room of all, which is that this is not simply a corporate issue – it is a political enabling. Heineken took all the criticism for the cutting down of the Monmouthshire orchard, but make no mistake – the people fundamentally to blame are the government.

In the noughties Andrew Lea was asked to conduct a study into the juice content of ciders in the UK. There was, at the time, no legal limit, and it transpired through his report that the majority of ciders hovered at around 30% juice, with some very much lower. One example was just 7% juice, and a quarter of the ciders served on draught at ‘a prominent Cider Festival’ were markedly less than full juice too.

Partially as a result of this study, with legwork done at the end of the New Labour Government, the Coalition Government of 2010 enshrined the 35% juice content mandate in Excise Notice 162.

It could be argued on the one (incredibly glass-half-full) hand that at least this prevented the existence of ciders at 7% juice. But to my mind Excise Notice 162 is the most demonstrable document imaginable of successive governments’ utter disregard for environmental concerns and for things being made with craft and care, quality of ingredient and respect for consumer transparency. It is an absolute banner for the most cynical excesses of capitalism; a tissue of loophole; a document that wilfully refuses to engage with what cider is for so many hundreds of small makers, businesses and customers.

Somewhat unexpectedly, this low minimum juice content was the subject of a minor coalition scrap. In 2013 the Liberal Democrats suggested that the minimum juice content of cider should be 75%. To which the Adam Smith Institute (a think tank whose transparency rivals Heineken’s, and which was instrumental in the Thatcherite privatisations) responded that this was a ‘silly and self-serving policy’ and that the Lib Dems had ‘a bizarre obsession with apples’, a feature of that party that had personally passed me by.

‘The proposals are silly,’ said research director Sam Brown. ‘More than doubling the amount of apple juice required for a drink to be defined as a ‘cider’, taxing any that do not change out of the market. That would mean that many popular ciders like Stella Cidre and Strongbow, with apple juice contents of around 50%, would either have to change significantly or become unreasonably expensive.’

Excise Notice 162 actively rewards the use of concentrate in reducing its stated legal minimum percentage. It rewards sourcing cheaper apples from countries outside the UK and thus incentivises the removal of orchards within it. What’s more, with its baffling stipulation that, past 8.4%, ciders fall into the wine tax band, it lumps the most cynical and predatory white cider brands in with the very best and ripest fully fermented ciders from the finest apples and most exemplary vintages, punishing the latter for being as good as they can possibly be.

But then governments and political bodies, both in the UK and abroad, have wreaked such havoc on cider and perry and orchards and trees in the last century that for Excise Notice 162 to be any different would be actively shocking. We’ve seen it in the 11 million trees cut down in Switzerland between 1950 and 1975. We’ve seen it through the classification of traditional perry pear orchards in the Domfrontais as simply ‘meadows’ for not having a high enough tree density, denying them the orchard grants that might have saved them.

In the UK we’ve seen the Long Ashton Research Station completely defunded and ancient pear trees cut down for railway lines that aren’t then built. We’ve seen 90% of traditional orchards allowed to fall into disarray and we have seen the demolition of orchards, the abject lack of transparency in cider and the cynical whittling down of ingredient cost and product quality all rewarded at the expense of consumers, trees and the broader environment.

Railing against macro cider itself will change absolutely nothing. Their financial imperative will always hold greater sway than any other concern. What’s more, the way they make their cider is – and should be – entirely up to them. Nor is this article about the demonisation of macro ciders themselves, and certainly not the many thousands of people who enjoy them. It’s not for me to tell anyone else what they should or shouldn’t drink, or how they should or shouldn’t drink it.

What I do want is an imperative towards transparency. For it to be clearer what ciders are made of, and why one is different to another, so that consumers are in a position to make an informed choice. I want policies that protect the vital environmental resource and national heritage that orchards, particularly cider apple orchards, constitute, both through formalising the kind of listed status afforded to old buildings, and incentivising the use of their fruit.

If the legal minimum juice content for ciders in this country was raised to a paltry 50% – far below what I would personally choose – that orchard would still be standing. If there was a legal requirement for British cider brands to use only British apples, that orchard would still be standing. These places should and could be fêted sources of wonder, pride, clean air and biodiversity, with the ciders they made held in the highest global regard. But that won’t – indeed can’t – happen without direct political intervention, of the sort that recent governments have clearly had active disinterest in taking.

I also don’t feel that the impetus for this change will – or even could – come from the National Association of Cidermakers. Though the Association’s stated aims include the promotion of the cider industry, encouragement of their members to be responsible businesses and endorsing a fair and balanced legislative platform to enable cider to compete in the marketplace, a glance at the headline names on their website shows that campaigning for the sort of transparency of practice and protection of orchards that I feel is necessary would be actively against the interests of their most powerful members. The drive for change must come from elsewhere; beginning with those who care most deeply about the apples, the trees, the land, and the people who strive their utmost to bring them into sensitive confluence. It must come from us.

The state of cider and orchards is, of course, low down indeed on the long, long list of reasons to exercise the democratic right that those of us in the UK are privileged to have. And I acknowledge that anything I write on the subject of orchards and cider is laden with personal bias.

But so much of what I have written here can serve as a microcosm for broader societal issues. Issues of transparency for consumers of any good or service. Of playing fields that are level, not deliberately engineered to enable the biggest, richest businesses and individuals to profit consistently at the expense of the smaller. Of climate breakdown that is currently being wilfully accelerated even as we feel its catastrophic effects more keenly year on year.

Cider is a privilege. But it is a small thing which, at its best and most transparent, is both a benefit to the environment and an important source of shared joy. My world would be reduced without it, and if you are reading this I’d bet that so would yours. Ultimately, perhaps sadly, it is the threat to pleasures and privileges that inspires the majority of us to take action. And make no mistake, cider and orchards as we know and love them have been under political attack for decades. As we learn from the Monmouthshire orchard, they could easily vanish tomorrow.

***

Walking down the Artistraw orchard hill, the view splays out over the western mountains and the rolling downs to the north. Cider and orchards suffused this place; every field and farm once thronged with fruit, now a bare-green, ghostly, sheep-pocked memory. As we reach the bottom the wind gusts blowsy and chases its way up the orchard slope following the path we left. It billows through the fronding, feather-fletched grass then fills the sails of the new-green apple tree leaves, rises through the old oak at the top of the hill and at last is lost forever in the ancient blue.

Discover more from Cider Review

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

That is a brilliant article, Adam, even if one which is full of sadness. Three things I’d note (one self-promoting!)

All in all it’s easy to be despondent. We just strive to do our best, earning a paltry return for lots of time and love put into creating our apple juices and ciders, just like many other producers.

Oliver Dowding

LikeLike

Draft of the new cider according to me…

“Cider” needs to be 90% by volume from fresh apple juice and must be labelled either NV or with a vintage (it must be 90% of the labelled vintage). The remaining 10% can be juice/pulp of fresh fruits other than apples. Flavouring may not exceed 5% by volume.

“Perry” as above but with pears.

Any products that don’t confirm must be labelled and advertised either Blended Cider/Perry Product or BCP/BPP.

While we’re at it, only 100% UK grown apples can be used in the aforementioned cider and perry. Otherwise it’s BCP/BPP! Not sure if exclamation marks are allowed in legislation, but let’s leave it in for now.

Then all that’s left is to educate people about the difference.

Oh, and levy all producers making over 50,000 litres annually a small % per litre to fund a governing body to enforce the legislation. Plus producers under 500hL have their excise rebated annually.

Good luck with it.

LikeLike

The term Vintage in cider is to describe vintage quality apples, not age.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cider_apple

LikeLike

Hi Tim. Thanks so much for reading and taking the time to comment. Really appreciated. ‘Vintage’ is a funny one in cider, isn’t it? I’ve read records going back to at least the 17th/18th century that definitely use ‘vintage’ as a designated year but know plenty of cidermakers who’d only really use it in the LARS ‘vintage quality apples’ sense. My take would be that both terms are clearly historically legitimate, but there’s maybe a broader church outside of the already-converted cider bubble who are more familiar with it as a designation of year than variety.

Thanks very much again for reading and commenting.

Adam W.

LikeLike

Pingback: Distilling the orchard’s spirit — An interview with Sam of Wilding Cider | Cider Review