Mousiness, as a cider fault, will be familiar to CR readers. It’s been mentioned on Adam’s On Matters of Taste and also features in CR’s guide to identifying cider faults. Yet it remains a bit of a mystery. Many cider drinkers are unfamiliar with this fault or unable to confidently identify it, beyond citing the well-known and rather unsavoury description: like the bottom of a mouse cage. And who in the world has first-hand experience of that?! I, for one, remain blissfully ignorant.

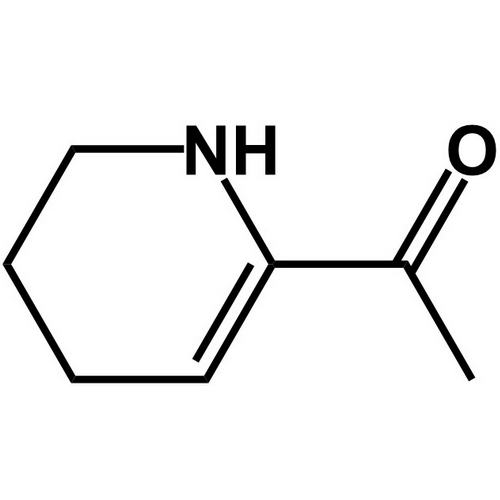

A number of other factors contribute to the elusive nature of mouse. Sensitivity varies a great deal between individuals. About 40% of people are unable to taste Tetrahydropyridine (THP), the compound that is responsible for this fault. There has been relatively little research on the formation of THP in wine – let alone cider and perry. Many open questions regarding the specifics of THP metabolics remain unanswered. It appears – and sometimes disappears – without obvious cause. And, understandably, producers prefer to keep the subject quiet. All the more reason for us to take another close, hard look at THP from the perspective of a cider drinker.

Identifying THP

THP is unlike other faults in that it is not always immediately noticeable, but rather develops and builds up over time. The first sip of a mousy cider can be completely enjoyable; but after a while the lingering flavour becomes apparent and builds up. It is mostly perceived retro-nasally, i.e. when exhaling after swallowing. Reminiscent of corn chips or stale biscuits, it is not terribly offensive as such – but just plain wrong when tasted in a cider. The flavour also lingers for minutes, detracting from anything else that might be enjoyable about the drink, making it doubly objectionable.

Perception is linked to the pH of the drinker’s saliva, so the less acidic your saliva, the more pronounced the effect as it makes the compounds more volatile. Food changes this pH, so some foods thus serve to either decrease or enhance the perception of THP. I find that a mild, creamy cheese will really put a spotlight on any THP that might be present.

Intensity also increases with exposure to oxygen. After aerating the drink in your glass or allowing it to sit for a while, you may detect THP that was not noticeable before. The effect is really pronounced when you put a half-empty bottle in the fridge and pour another glass the following day.

The Science of THP

MilkTheFunk has an excellent and very in-depth page on THP, which I have leaned on heavily. If you want to dive even further down the rodent hole, this is a great place to start. Meanwhile, let’s review the major scientific findings, as they pertain to cider:

THP is produced by a number of organisms. Chief among these, and most relevant for alcoholic beverages, are Lactobacillus and Brettanomyces. Sulfite inhibits Lactobacillus; pre-emptive sulfiting can therefore prevent mouse. On the other hand, elevated temperature promotes the activity of Lactobacillus. Unseasonably warm weather is becoming more common, creating challenges for cider-makers that ferment at ambient temperature.

Brett has a much higher tolerance for sulfite, so preventing cross-contamination through good sanitation practise is the best option for controlling it. Additionally, THP production by Brett can be inhibited by depriving it of necessary nutrients, i.e. keeving or racking off the lees.

There are multiple varieties of THP, of which some (ATHP, APY) are up to 1000 times more flavour-active than others (ETHP). It amazes me, that humans are able to detect APY at a level as low as 0.1 µg/L – that’s 1 part in 10 billion! ATHP can be converted to ETHP over time, reducing or eliminating the detectable off-flavour. Interestingly, Brett both produces THP and metabolizes ATHP to ETHP – so it may be either beneficial or detrimental.

Unfortunately, the conversion can go the other way too, turning relatively benign ETHP into evil ATHP through oxidation. This is why mousiness becomes more apparent the longer cider is in the glass and exposed to air. Cider-makers need to be vigilant about minimizing oxygen exposure throughout the production, from fermentation to bottling.

If this all sounds pretty cut and dried, I hasten to add that the science is far from conclusive. There are still many aspects that are poorly understood or need more research. In particular, understanding the contributing factors: Brett and Lactobacillus generally have a positive effect, creating a bit of funk and reducing malic acid. But what causes them to go off the rails? This is where the real world experience of cider-makers is invaluable.

The Role of Makers and Drinkers

A policy of “don’t ask, don’t tell” is detrimental to the improvement of the craft. THP is a growing problem in this world of climate chaos, and the more we learn about it and share that knowledge, the better equipped we will be to deal with it. Not every producer wants to sulfite or is able to control the temperature of a ferment. But I am convinced that by developing a more nuanced understanding of THP, we can continue to successfully use traditional, low intervention approaches to cider-making.

It should go without saying, that no self-respecting cider-maker should be sending out mousy bottles, assuming that consumers won’t notice; or in the hope that it will age out before the bottle is opened.

Cider drinkers for their part should not be shy about rejecting THP-tainted cider; while understanding that THP may well have developed after bottling, without the producer’s knowledge or ill intent. Only by fostering an open, two-way conversation can we come to grips with the problem and protect the value of artisanally crafted cider.

A Reevaluation of Mouse

I hope this has eliminated some of the mystique of mouse and you feel better equipped to recognize and deal with it. It could be as simple as: serve cider cold and drink it quickly – then you may never have to worry about THP. But readers of CR are a more discerning bunch, that occasionally enjoy slowly sipping a room temperature, low acid, wild fermented beverage. If you notice a faint hint of THP, consider cellaring the remainder of those bottles and trying again a few months down the line. Chances are good that it will have cleared up by then. But if THP is seriously interfering with your enjoyment of a drink, do let the producer know and give them a chance to make amends, and to learn from this experience.

Cover image from The Natural History of Quadrupeds, and Cetaceous Animals: From the Works of the Best Authors, Antient and Modern. United Kingdom: Brightly, 1811.

Discover more from Cider Review

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Thank you for this excellent article! I first tasted mouse when I was working with a lot of natural wines ( I once attended a tasting event of Pet Nat Wines where 6 of the 8 wines showing were completely riddled with it) and have since spotted it in ciders. I find the effects of mouse grow in the mouth to the point where I can’t taste anything else for some hours. The challenge can be that some serving the cider can’t identify mouse themselves and this can be very tough to overcome. Gabe Cook’s Pommelier course covers faults like this very effectively and practically.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Glad you liked it. A bit of a delicate subject, but the better we understand it, the better we are equipped to prevent it.

LikeLiked by 1 person