The history of German perry, well, like most perry I guess, always feels a bit elusive. While some of the more technical kinds of literature mention Birnenwein (the usual German name for perry), though far less than Apfelwein (cider), it is more difficult to find accounts of how perry was perceived and treated culturally. The whole southern half of Germany had regions, especially Württemberg and Hessen, where cider was once of great importance. But given the number of pear trees still standing in the great meadow orchards of the State of Baden-Württemberg, perry pears and perry most certainly played an important role in that. Not to mention the Bavarian peasantry was reputed to favour drinking perry in the Medieval period!

I’ve mentioned previously how important perry pears were to rural German agricultural communities in centuries past. They offered a source of carbohydrates to both humans and livestock, being used to make syrup for sweetening, or dried for use throughout the year, and the juice was fermented for drinking of course. But getting hard and fast details on the latter has always been a bit difficult, at least compared to some other countries.

A couple of years ago I published an article in the Journal of the German Association of Pomologists about the link between cider making and early British pomology (also published in English on this site), after which I received a few e-mails from fellow members of the association who had enjoyed the article. One of those mails opened a new thread of research into a German perry culture that I had not even know had existed: an apparent former stronghold of perry culture in the Westpfalz (Western Palatinate), an area that is now part of the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate that borders Belgium, Luxemburg, and France.

The Rhineland-Palatinate is well known for wine, particularly along the Rhine valley, where Germany’s oldest tourist wine route, the Deutsche Weinstraße, runs from its southern border with France down the Rhine for some 85km. But head west of the Rhine Valley, across the wrinkled landscape of the Palatinate Forest, traversing a roughly north-south line drawn between Kaiserslautern and Pirmasens, and you enter the Westpfalz, which extends west till it hits the border of the tiny neighbouring state of Saarland. You won’t find vines here, but you will find perry pear trees. Perhaps not as many as there were even 70 years ago, but they are there.

My correspondent had told me of a perry museum in the small village of Eulenbis, near Kaiserslautern, and mentioned a map on display there that had indicated a region that was known for centuries as being famed for perry pears. A perry museum? I could hardly believe my eyes. It was all the catalyst I needed to start delving further on my own.

Sadly, I didn’t have the time to travel to the Westpfalz to see the museum at the time, though as a former map maker, I desperately want to see the map that he had mentioned. Nevertheless, some desktop research was needed, but at least this time I knew what to look for, and based on what follows, I created my own Google map that you can use as a guide.

Through the Valley of the Pig Pears

Our first stop is November 1955, when linguist Ernst Christmann (1895-1974) wrote a short article in a regional historical journal, the Pfälzischer Heimatbätter titled “’Saubeeredal’ und ‘Sauerbierenland’ – Wer weiß etwas davon?“. In the article he reported on how he had recently stumbled across these two local and apparently almost forgotten placenames that were both pear-related. “Who knows anything about them”, he appealed in the title.

It must be noted that as a linguist, Christmann had investigated the origins of Palatinate settlement names, field names and vineyard names, and during his lifetime had made a considerable contribution to wine geography. But here he was asking in print for more information about these two perry pear related regional names. But he did provide two fantastic starting references to work on.

At first glance one might assume that the word Saubeere might refer to some kind of berry, Beere being German for berry after all. But in the Westpfalz it would appear that Saubeere is actually a local name for wild pears, translated literally as “pig pears”. Sau being a sow, and beere being an inexplicably strange old local dialect word for Birnen (pears). We see similar names in other regions, like the Swiss Sülibirne from around Lake Constance meaning “little pig pears”, or the Austrian Saubirne, from which Subirer schnaps is made. I imagine it may hark back to the practice of feeding such wild, bitter pears to the pigs, perhaps even before people realised that they make a fantastic perry too. Saubeeredal therefore translates as pig pear valley, the final piece “Dal” being local dialect for Tal (valley).

Christmann had referenced Julius Wilde (1864–1947), a botanist who in 1923 published a book on the local plant names of the Palatinate. In “Die Pflanzennamen im Sprachschatze der Pfälzer”, Wilde had an entry for Saubeeretal, and listed its geographical delineators.

“The small valley that leads from Diedelskopf via Bliedersbach to Hüffler is called Saubeeretal. It owes its name to the many wild pears that grow there”.

(Wilde, 1923)

Christmann noted that as Wilde was from the Vorderpfalz (Anterior Palatinate) region and not the Westpfalz, some of the names were not quite right, and provided corrections. Diedelkopf not Diedelskopf, Bledesbach not Bliedersbach. The latter is a stream whose source is near Wahnwegen, flowing through Hüffler and Schellweiler, and finally through Bledesbach, a village given its name by the stream, before flowing into the river Kusel at Diedelkopf. This is the Saubeeretal.

It’s interesting to think that this small valley, running only about 7km long, was once renowned enough for its wild pears that it was christened valley of the pig pears. Even the denizens of this valley were referred to as “Saubeeredääler”!

Christmann wrote that by 1955, and by then he had had many walks in that exact valley, the wild pears that once gave it its colloquial name didn’t seem so prevalent. But placenames have a persistence, a window on the past.

Out of the Land of the Sour Pears

But it doesn’t stop there. Christmann had also mentioned a “Sauerbierenland”, citing letters written by Kurfürst Karl Ludwig – or to give him his full title in English, Charles I Louis, Elector Palatine, Palatinate Count of the Rhine, Archtreasurer and Elector of the Holy Roman Empire, Duke of Bavaria – in the 1670s.

Charles Louis was nephew to King Charles I of England, and he spent quite a lot of time there, especially during the 30 Years War. A war, I should mention, that had been more or less sparked when his own father, Frederick V of the Palatinate, accepted the Bohemian Crown 1617 pissing off Emperor Ferdinand II in the process. Charles Louis was practically in exile while that dreadful war was ongoing. It was said that while there, he had sympathies towards the parliamentarians during the lead up to the English Civil War, and that his uncle even suspected him of having an eye on the throne. But he returned to the Palatinate in 1649 after the Peace of Westphalia, signed just the year before, ended the 30 Years War and returned the Palatinate to him. He left England just after his uncle Charles had been executed.

Charles Louis had some considerable rebuilding to do following the destruction of the Thirty Years War, and was clearly travelling a lot around the Palatinate, keeping diaries and writing letters as he went. A collection of these was published in 1885, and Christmann referenced this collection in his query about the Sauerbierenland. Thanks to the Internet, a full copy is available online, so I was able to search for the full quotes for added context, as well as finding a third. We begin in Neustadt, Saturday, August 28th, 1669, 5 o’clock in the afternoon:

“Meanwhile we arrive here through great heat and dust, which my dear could hardly have withstood. At the same time, two messengers with two baskets of grapes arrive from our canaan, one for my treasure, the other for Liselotte [his daughter]. I have filled my belly with them before we arrive in the land of the sour pears [sawer-pieren-land], where we will have to eat herring. It will certainly go well there, after all dancing and side games are forbidden in that country”.

(Holland, 1855 pp209)

That was written in what is today called Neustadt an der Weinstraße, on the very eastern edge of the Palatinate Forest, but still very much part of the Rhine Valley wine region. And clearly the grapes were good back in 1669 too! He then travels about 35km northwest, across the Palatinate Forest, and a couple of days later writes from Kaiserslautern:

“Lautern, Tuesday, Aug. 31, 1669, in the land of the sour pears [sawer-pieren-land], where the grapes are so hard that one can shoot the sparrows to death.

I received the letter from my dearest on Sunday, together with the kind package of food, last evening, for which I thank you . . . and will probably need it in the Westrich, when it will be placed in a chamber with two s. h. [no idea!] as it is here. I hope that my letter, which I sent with the grapes from Neustadt on Saturday, will have arrived safely and that the grapes will have tasted good”.

(Holland, 1855 pp210)

So this places Kaiserslautern as being in the Sauerbierenland, apparently not a great place for grapes, but it doesn’t do much to define what the extent of that region actually is. A few days later he is back into the Rhine Valley and wine country when he ends up 50km northeast in:

“Alzey, the 4th of September, 1669.

Yesterday I came here from land of the sour pears [saurpiren-land], the day before I received my dear letter of September 1 at Meisenheim. If I had stayed there longer, I would have become a wine or water drinker, because I could hardly eat anything, everything was salted, peppered, poisoned, except for the crabs, from which I got my Greek disease, but without pain, but yesterday evening, when I arrived here, I had a severe headache, which I expelled with a whole glass of Bacharacher [presumably wine from Bacharach, some 50km NW of Alzey] and a little water on top”.

(Holland, 1855 pp211)

So that that’s three times Charles Louis mentions the “land of the sour pears”, but he clearly didn’t think very much of the area. Christmann seems to have interpreted this as meaning that the entire Westpfalz was the Sauerbierenland, but I think it’s far too little evidence to conclude that. And while it might well mean the area around Kauserslautern was populated with lots of sour, wild pear trees, Charles Louis may have been using it as a derogatory term. He certainly didn’t mention drinking delicious perry!

Christmann went on to mention that in January 1677, Charles Louis wrote to his sister, Princess Sophie of Hannover, expressing concern about events in the Sauerbiernenland.

“I thought I was writing a nice message to my dear niece, the Princess Phiguelotte, by sending her a few crotesqueries, but this crush of the Saur Piren Land and the fear that he will also become attached to the land of Canaan, does not leave me free-minded until we can find a remedy”.

(Bodemann, 1885)

I could not find any reference to a destruction of Kaiserslautern in early 1677, but Kusel, 30km to the west, was heavily damaged, with parts of the town destroyed and burned by King Louis XIV of France’s soldiers during the Franco-Dutch War.

Could Charles Louis have been referring to the events at Kusel? Was the “he” he referred to King Louis? At least this would mean that the Sauerbierenland was not just the area immediately around Kaiserlautern, but extended to Kusel. And as Kusel sits just at the north end of the Saubeeretal, as described by Wilde as recently as 1923, I could accept that it extended that far. But not Christmann’s proposal that this included the entire Westpflaz. Well, not just yet. But at least Christmann himself asked the question of whether this was a name that was in common use or was it just Charles Louis’s own nickname for a place he didn’t seem to particularly like, so it seems he was not quite sure himself. For that we’d need more hard evidence.

But for now, it suffices to say that at least the northern parts of the Westpflaz were once known for their wild, sour pears. But what about perry?

Beerewei and Beerebumbes

Wilde, who had given us a precise definition of the Saubeeretal, also provided a long list of local dialect names for the perry pear in general, some of which are very entertaining: Mostbeer, Weibeer, Woibeer, Schnappsbeer, Krebbeere, Krebbe, Bummbeer, Dumbeer, Wergelbeere, Werjelbeere, Wäjelbeere, Dornbeere, Saubeere, Säubeercher, Sauerbeere, Mäbeere and Annelcher.

For us though, the names for perry the drink are perhaps more interesting. He said that perry is generally called Beerewei in the Palatinate, not too far off Äppelwoi, the local dialect name for Apfelwein in Hessen next door. But then you get to names like Beere-Bumbes and Beerbuff. I still can’t explain why Birne became Beere, but Beere-Bumbes is perhaps my favourite ever local name for perry. There are a few interpretations of where the Bumbes came from, ranging from the shape of the pears suggesting a potato dumpling called Bubesse, from Bombel meaning a ball, or perhaps from an old rhyme, Bumbel de Bumble de Hollerstock, and it’s something to do with beating the pears to crush them before pressing. Or maybe from aufstoßen, burping, in local dialect called uffbumbse. Some, perhaps wanting to gentrify it, suggest Bumbes may come from anstoßen, or bumping the cups together in a toast. In an 1872 book for folk terms around Nassau, some way to the north, a Bumbes is a round bellied jug, suggestive of the Bembel famous for serving Apfelwein in Hessen.

It should be said that from the 18th to 19th Century, there are quite a few mentions of perry, cider and fruit wine in general in books of old laws, specifically taxes, but no great details on use or amounts. Although, Dieter Zenglien, writing in 2014 said:

“Since the increasing consumption of perry (or cider) meant competition for the wine business, the Trier city authorities also kept a strict watch to ensure that not too much entered the city. In October 1787, a decree was issued that every citizen of Trier was to be allowed, according to old custom, 2 ohm (approx. 160 litres) cider and perry may be transported into the city for ‘personal consumption’. Additionally imported quantities were subject to a tax. However, this was not enough for the citizens of Trier, and in October 1789 a new decree was issued, according to which the citizens were now allowed to import twice the amount, i.e. 4 ohm (approx. 320 litres) per year ‘for their own consumption’”.

(Zenglein, 2014)

Despite asking at the City of Trier itself, I could not find this precise law, but there are several mentions of taxation on Apfelwein and “Birnentrank” (literally “pear drink”) in the old lawbooks of Trier, right up to the 1850s, which while some distance away from the Saubeeretal, and being on the Mosel in absolute prime wine country, certainly shows that farmers there were making perry there too.

Everyday tales

But the word Beerebumbes led to another great find as, by chance, while shopping for books on German pears, I stumbled across a 2014 newsletter from local history society in the West Palatinate that had dedicated a volume to a series of articles on pears in that region. One article, by the aforementioned local historian Dieter Zenglein, focussed on old traditions including perry making. He included additional references to less formal literature, leaning more into first-hand accounts from people who had grown up surrounded by that perry culture. I feel that is where all the juicy bits really are, the links to the people who were steeped in such traditions.

One such account came from Paul Drumm, born in Ulmet in 1901, the son of an old-established, wealthy farmer’s family, though he had left home to work as a teacher. In 1981 he described rural life in great detail in his book “Wie einst es war, ein Dorf im Wandel” (how it used to be, a village in transition). Of special interest to us is his description of the perry pear trees and of the making and drinking of perry.

“A special feature were the large perry pear trees that stood around the village. They lined the field tracks, but also stood as prominent individual trees far out in the district. We had about ten such trees, some of which were 200 and more years old. Some of these trees gave a whole wagon full of pears. After the railway was built in 1904, traders from Württemberg came and bought pears. Many wagonloads went across the Rhine in autumn so that the Swabians could get enough Most. But every farmer also pressed the pears himself and filled his barrels in the cellar. There were two wine presses in the village where the farmers could grind their pears for a fee. They have both disappeared…”.

(Drumm, 1981)

He went on to describe the construction of these old stone and wooden mills and basket presses in great detail before returning to the topic of the juice and fermentation process.

“The sweet juice was of course tried by every visitor who passed the winepress, and many made a diversion on this occasion. We boys liked it so much that we often drank to excess. In the course of the day, sometimes not until the next morning, the consequences became noticeable. But an occasional thorough cleaning of the intestinal tract is supposed to be a good thing. It was just unpleasant when it interfered with school lessons in the morning.

The juice was carried home in buckets and filled into the freshly cleaned and sulphured barrels. They were stored on two strong oak beams behind the Krautstein [the earthenware pot for making sauerkraut]. Now it fermented in the cellar. When the effervescence was over after 2 – 3 weeks, it was sealed shut and the perry remained on the yeast. There was always a tap in one of the barrels, so that “Beerwein” could be fetched from the cellar at any time.

On winter evenings, a jug full was brought up, warmed by the stove and drunk in the course of the evening. At the slaughter fest, jugs of perry circulated. When threshing, the perry helped to wash down the dust and drive the sweat from the pores. Perry was drunk in the morning with a snack and went with the mowing in the meadow. And at sowing time, the perry jug dangled from the horse’s collar all the way to the field.

Today, the large pear trees have almost completely disappeared. Even without the emergence of new drinking habits, they would have had to make way for the mowing machines, the combine harvester and for the heavy farming implements. Other drinks: beer, lemonade, fruit juices have replaced perry. The old wine presses have been torn down; the old barrels have been sawn apart… The old cooper in Erdesbach died decades ago without a successor”.

(Drumm, 1981)

A fascinating account of how perry was very much part of everyday life for farmers in that region up to the first half of the 20th Century, but also rather tragic that by the 1980 it was pretty much all gone, a sad victim of progress.

Liesel Höh was another octogenarian who, encouraged by Dieter Zenglein himself, wrote about farm life in her 2000 book “Im Tal der Kirschenbauern” (in the valley of the cherry farmers), when she was 85. Liesel also recalled that large amounts of pears, the Saubirne in particular, were sold and transported out of the region by rail. It’s a fascinating book, giving a detailed account of what village life was like in the early 20th Century, and she also recounts how her family made perry, mostly using the “Saubeere”, with their own equipment: a stone wheel and wooden trough as a crusher and a fancy wine press while, generally, it appears that community presses were the norm in the villages of the region.

Zenglein provided many more first-hand accounts of making perry in the early part of the 20th Century, and while I would love to recount them all, as they provide a sense of the everyday connection the farmers of the region had with perry, I fear the word count would get rather excessive, even by Cider Review standards! But it did allow me to put some extra dots on the map. But I will end with one more quote that illustrates how integral perry (and indeed cider, though apparently only after the first World War in that region) was to everyday life in the Westpfalz, from Friedrich Wilhelm Weber.

“During the week, we drank home-brewed grain coffee (as well as water), a liquid that didn’t always meet with enthusiasm from the men. For the second breakfast they had ‘Eppelwei(n)’ or ‘Beerebumbes’ with home-baked bread with Handkäse[a kind of home made sour milk cheese] or Kässchmier[a cream cheese]. For lunch, snacks and dinner, the men would fetch their jugs of perry from the cellar. This house drink was of great importance when working in the fields, which largely involved physical labour. A large number of helpers were needed for hay and grain harvesting, for potato digging and threshing. So it was good that fruit wine was available. As it did not contain a lot of alcohol, it could also be drunk to quench thirst. It was wholesome, invigorating, generally beneficial to the body, and an indispensable part of the life of the labouring country dweller”.

(Zenglein, 2014)

The Frankelbacher Weinbirne

No tale of perry from the Westpflaz would be complete without at least mentioning one of the most famous varieties of perry pear, the Frankelbacher Weinbirne (the Frankelbach wine pear). The mother tree stood in a field just outside Frankelbach, a small village 14km northwest of Kaiserslautern. It was estimated at being at least 350 years old by the time it was felled, but local legends put it at thousands of years old. It was said to produce up to three tonnes of fruit in a year. Its trunk was just over 6 metres in circumference and it had an estimated crown diameter of nearly 20 metres. It was clearly a massive tree! At some stage the mighty trunk had been cloven by lightning, but the tree lived on, iron bands later supporting the trunk like rings on a huge barrel. In 1926 Ludwig Rösinger, a teacher from Frankelbach, wrote the following:

“Just as the people of the Vorderpfalz and the Rhineland have taken their grape wine to their hearts, the people west of the Rhineland have another drink that some people could almost not live without: it is the Beerewein [perry]. You only have to go to the right source and taste it, and you will be amazed at what Bacchus has given the people of the Westpfalz as a substitute for the glowing juice of the vine. Many a person has made a puzzled face when, after a refreshing drink, they were shown the ‘vineyard’ that produced the delicious liquid. Instead of well-tended vines, the gnarled, weather-hardened wine pear tree stood on the hillside and murmured in its branches and twigs the events of many, many years. It is not the location of the ‘Beerebam’ [pear tree] that is decisive for the quality of the juice, although it is of course also of great importance, but the variety and type of pear. In the Palatinate and far beyond its borders, the ‘Frankelbacher’ pear enjoys an excellent reputation. On the slope of a beautiful side valley of the Lauter from Olsbrücken stands the ancient grandfather in the ‘Orsborn’ field, who had to supply the shoots for the scions for grafting the pear trees not only of the immediate surroundings, but of the entire Westricher Gau and neighbouring regions. No grandfather of the old Frankelbach farmers still alive remembered that this tree was transplanted there. There is such a sacred respect for its age that the whole region is of the opinion that it is already 2000 years old, there at the time of Christ’s birth, when the old Germanic tribes still lived in the forests, this ‘primeval tree’, as it was called, must have sprouted from the then still heathen soil. Its age now requires crutches. Even though it bears its precious fruit every year, the ravages of time have already taken their toll on it. Its not so solid trunk has been split into three parts by storm and weather, but in the earth they still remain firmly united. Two men can stand in the middle of it and three men can barely grasp the massive giant, which is saying a lot for a pear tree“.

(Rösinger 1926)

Ten years later the mother tree was gone, felled for firewood said one newspaper, but perhaps it had to be removed for safety as it finally fell victim to its wounds and age. But as Rösinger said, its progeny lives on, and I’ve grafted some myself.

The decline of perry in the Westpfalz

The Westpfalz is unusual in Germany, in that it appears to have been one of the last bastions of perry making in the entire country, where perry was such an integral part of life and culture, and just about still in living memory. But what happened there?

It seems to be a tale that has been replicated across central Europe since the 1950s. Whether it was in Switzerland with the “tree murders”, across Baden-Württemberg where I am, where I know much of the former landscape that was covered in fruit trees was lost to the “Flurbereinigung”, or land consolidation processes that were needed to support the development of modern agricultural processes from the 1950s on. And it’s still happening! And now we see it also happened in the West Palatinate, where a true German perry tradition had persevered for so long. An insidious and slow erasure of a cultural landscape all over southern Germany.

Let’s turn to the moving words of Hans Weckerle, a horticultural officer in Kaiserslautern, who in 1962, summarised the slow death of this tradition, and the trees that had driven it for so long:

“Oak, beech and lime trees are generally regarded as the giants among our native trees when fully grown. But even our perry pear trees are not inferior to them in size and attainable age. After all, the natural monument ‘Der große Frankelbacher’ was a perry pear tree in the Lauter Valley, one of the largest in the Western Palatinate. With its estimated minimum age of 300 years and its trunk circumference of 9 metres [earlier writers said 6.25] with yields of up to 60 hundredweight [3,000 kg!] of perry pears, it was for centuries the mother tree of numerous descendants in the districts of Kaiserslautern and Kusel, until it was felled by lightning while still in the best of health. Its descendants, grafted by the farmers themselves onto strong-growing wildlings, have now grown into giants themselves, but they will not be granted a natural demise.

A glance at the landscape reveals the disappearance of these old, powerful landmarks of the districts more and more from year to year. Why did these giants have to fall and why will they still fall? The reasons are economic. Perry pears, which were in great demand until a few years ago, are no longer in demand. The economic miracle with its generally noticeable refinement of taste has rejected perry, pear juice and pear brandy. Pear syrup, once a main spread on bread, is now only known to the young by name.

The modern cultivation of fields with machines does not tolerate trees that stand in the way. Land consolidation measures and the clearing of uneconomical fruit trees have greatly reduced the number of giant trees. Modern tree-cutting tools such as tractors, winches and chainsaws can do in a few minutes what used to take several strong men several days.

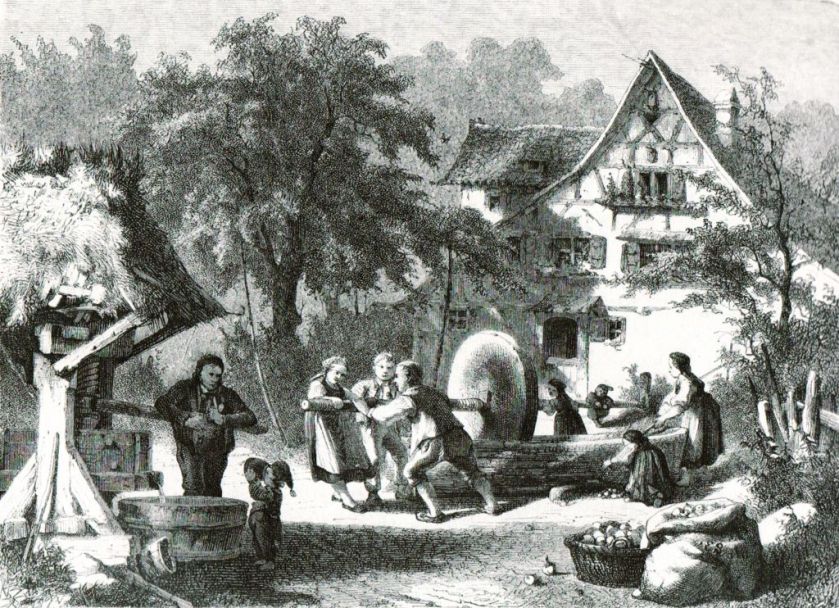

Closely linked to the fate of the giant fruit trees are the massive stone mills and stone vats in which the Westrich farmer’s drink, pear wine, was once produced in rough quantities. Fresh and sweet from the wine press, it was also sold in the streets of Kaiserslautern directly from large barrels in carts, accompanied by the shouts of the youth ‘Beerewoi – viel Wasser droi’.

Perry made in the old way, in stone mills and wine presses, is only still produced in the Pfeifertal valley in the Mückenmühle. If the horse-driven cider mill is still used with preference by the farmers from the surrounding area, then it is only for the one reason of allegedly obtaining a better tasting drink than from the modern and efficient iron wine presses.

But this cidery will soon be a thing of the past, like so many others in the district that were in operation only a few years ago. It is to be feared that indifference and the hammer will cause the few remaining beautiful stone monuments to decay and be smashed”.

(Weckerle, 1962)

Perry in the Westpfalz today

In effect, there is no perry in the Westpfalz today. I asked maker friends who live in the state, and while there is some cidermaking in Rhineland Palatinate, there is no perry being made commercially. Well, except one, kind of. A perry called “Prickelbeer” that was pressed as part of an awareness drive for pear tree conservation activities run by Streuobst Pfalz. But my attempts to acquire a bottle have not yet yielded fruit, and I don’t know if it was a one-off or not.

There are some distillers making pear schnapps, which I suspect became the main use for perry pears across most of southern Germany for the past several decades, as the need or desire for perry waned.

However, the old Westpfälzsiche perry culture is not entirely forgotten. What began this round of research was the mention of the perry museum in the small village of Eulenbis. The museum has a collection of artefacts and materials relating to, well, Beerewei(n), it is after all called the Beerewei(n)museum! From photos, I know this includes a sandstone trough and wheel crusher, various presses, glasses, harvesting aides and lots of photos of pear trees and people making perry from the past. It’s also pretty much in spitting distance of Frankelbach, and sits between Kauserslautern and Kusel, in what Carl Louis called the Sauerbierenland. Sadly, in a cruel twist of the tale, the mayor of Eulenbis recently told me that the museum is closed for the foreseeable future, and she didn’t tell me if there were plans to reopen in future.

One can only hope that the growing interest in perry that has been slowly creeping across Europe and further afield over the past couple of years can also take root in this former perry stronghold of the Westpfalz. The ancient sentinels are surely waiting for their day to return.

Accompanying map: https://www.google.com/maps/d/edit?mid=1cwijrk1h849Wj6RIC_s6P5hIS2e2-Tw&usp=sharing

References

Bodemann, Sophie. (1885). Briefwechsel der Herzogin Sophie v. Hannover mit ihrem Bruder, dem Kurfürsten Karl Ludwig von der Pfalz, und des Letzteren mit seiner Schwägerin, der Pfalzgräfin Anna. Osnabrück: Zeller.

Christmann, Ernst. (1955). ’Saubeeredal’ und ‘Sauerbierenland’ – Wer weiß etwas davon? In Pfälzische Heimatblätter vol. 3 p. 85.

Drumm, Paul. (1981). Wie einst es war, ein Dorf im Wandel. Speyer: P. Drumm.

Holland, Wilhelm Ludwig. (1884). Schreiben des Kurfürsten Karl Ludwig von der Pfalz und der Seinen. Tübingen: Literarischer Verein Stuttgart.

Höh, Liesel. (1984). Im Tal der Kirschenbauern. Jugenderinnerungen aus der Westpfalz. Altenkirchen: Eigenverlag.

Rösinger, Ludwig. (1926). Illustrierten Zeitschrift für den Fremden- und Touristenverkehr in der Pfalz, Jahrgang 1926, Nr. 32. Kaiserslautern: Pfälzische Presse.

Scotti, Johann Josef. (1832). Sammlung der Gesetze und Verordnungen, welche in dem vormaligen Churfürstenthum Trier über Gegenstände der Landeshoheit, Verfassung, Verwaltung und Rechtspflege ergangen sind nebst Nachtrag, Sachverzeichniß und Zugabe. Düsseldorf.

Weckerle, Hans. (1962). Ach du liewer Beerebaam. In Heimatkalender für die Stadt und den Landkreis Kaiserslautern. Neuwied-Rhein: Gerhard Dokter Verlag.

Zenglein, Dieter. (2014). Mer esse Beere on trenke Beere on hann noch Beere fer uf’s Brot se schmeere…! In Westricher Heimatblätter, November 2014. Landkreis Kusel.

Wilde, Julius. (1923). Die Pflanzennamen im Sprachschatze der Pfälzer. Ihre Herkunft, Entwicklung und Anwendung. Neustadt: Pfälzischer Volksbildungsverlag.

Discover more from Cider Review

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Having lived and worked in the Pfalz for six years I found this fascinating, well done. Unfortunately, I only ever came across pear schnapps!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, I’m glad you enjoyed it! 🙂

LikeLike

Barry, we still have a great cider tradition here in Trier. We call our cider Viez. Traditionally many farmers add pears to the Viez. We have special varieties for this. Sievenicher Mostbirne or Pleiner Birne. However, pure perry wine is considered inferior here and the word Birnenviez is very pejorative. Bieren or Beeren is simply the dialect word for pears and has nothing to do with the High German word for berries/Beeren. I would like to tell you more: On August 24th we celebrate the Viezfest in Trier, a cider festival. Would you like to be there as a guest of honor? Orherwise I can send you a cooy of my book „Viez“. Greetings from the Trierer Viezbruderschaft, Ernst Mettlach

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hallo Ernst!

Thank you for your comment. Yes, I’m familiar with Viez, and over here in North Baden where I live, we have the very same tradition of adding a quantity of Mostbirnen to the Most, something the old farmers also told me about, and I’m happy to continue that tradition.🙂 Pure Birnenwein and its history is almost my obsession, but I’m happy that at least that apple-based Most/Apfelwein/Viez still has a living tradition in Germany.

It’s funny that Birnenmost is now considered inferior in your region. There are records of Birnenwein being taxed in Trier in the past, but the locals being very upset, so the personal allowances to bring Birnenwein into the city were increased 😄

Though historically in southern Germany it was often said that it did not keep as long as apple-based Most, there are also a great many examples where it was compared favourably to wine, and the Swiss (and the Austrians still) certainly were famed for it.

I love the Beere/Bieren dialect word, and did figure that out. And of course in our region, as in the Pfalz I believe, potatoes are also called Grumbeeren! Everything comes back to pears 😄

Thank you for the invitation, I’d certainly welcome a chat! I’ll get in touch with you by mail.

LikeLike

Pingback: Nibbles: Cheese microbes, OSSI, Mung bean, Sustainable ag, Agroecology, Collard greens, African orphan crops, Olive diversity, Mezcal threats, German perry, Spanish tomatoes, N fixation – Agricultural Biodiversity Weblog

Pingback: Discovering Viez: The Mosel-Franconian Cider Culture of Western Germany | Cider Review

Pingback: Cider Review’s review of the year: 2024 | Cider Review

Pingback: Pyrus Invictus – Barry’s CraftCon 2025 Keynote | Cider Review

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comment, Leslie, a reminder that writings are often of their time and should sometimes be read with that in mind.

However, I will leave the quote as is, as it is not something I read as literal, I see it more indicating the importance and mythology of such a huge old tree in the local population, as he wrote “the entire region is of the opinion…”, etc. Opinion is certaily not fact in this case 😀

Later I wrote that the tree was actually estimated around 300 years old by the time it was cut down, which is about right for the lifespan of a perry pear tree; no pear tree could live to 2000, sadly, and our regular readers will kow that.

LikeLike

Pingback: Pyrus Invictus – Barry’s CraftCon 2025 Keynote – Kertelreiter Cider

Pingback: Pyrus Invictus – Die unbesiegte Birne – Kertelreiter Cider