In part one I outlined the backdrop that led to the so-called reorganisation of fruit growing in Switzerland and the type of people that drew up the plans. It’s a complicated series of events and situations that bring us to this point, but I hope I was able to boil it down to the key aspects. In this part, we’ll take a walk through the events on the ground from 1950 to 1975, and the repercussions this has had on a once vibrant perry and cider culture, still felt today.

The execution of the plan

It’s hard to understand the motivation and language used around this entire operation. There was really a hardcore, unwavering belief at the top levels of the Alcohol Agency that what they were doing was absolutely right and the only way forward. When Kai Bergengruen expressed the view that much of Hans Spreng’s work stemmed from a time of fascist ideologies, with a desire for control and perfect order over even nature, I could easily understand this view after reading details of the actions of the architects of the plan.

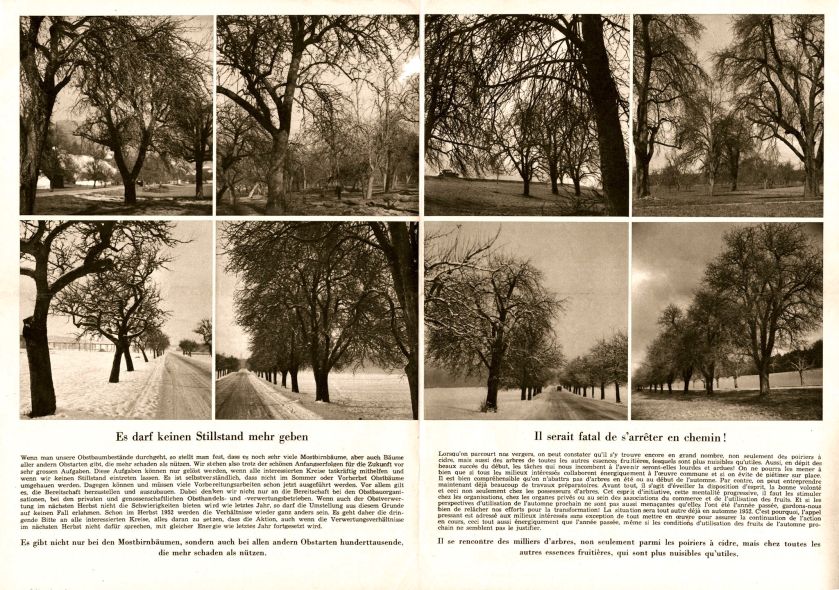

Although there was great stress put on the idea that everything would be voluntary for the farmers, there was considerable pressure put on them right from the beginning to basically get rid of their old trees. The language adopted to describe these trees was particularly degrading. They were called “loss trees”, parasites, non-productive and generally portrayed as being in the way of progress.

This idea of progress and order seemed paramount, and the advisors sent out to convince farmers to allow their trees to be removed would often leverage generational differences to get their way. It was put to the younger generations, who were eventually taking over farms from their fathers, that the trees in this agroforestry style were obstacles, both literally and figuratively. As there was increasing mechanisation with more tractors and equipment for tilling or managing hay harvesting, machines that were certainly appealing to the younger farmers, this was an easy way to set them against the older population, for whom the trees were an integral part of their way of life for generations. There are some desperate accounts of sons being set against their fathers, at least one with tragic consequences. Fathers, not wanting to stand in the way of their son’s futures, eventually stopped protesting.

Franco relates accounts telling of how advisors would try to convince the farmers to remove every old tree, perhaps starting with marking a few for removal where it made most sense, then cajoling them for one more, and then another, and then another. If that didn’t work, some less scrupulous advisors would resort to bullying and belittling the farmers, telling them they were nobodies who hadn’t a clue, and they should just do what they were told.

It should be added that farmers were also paid for tree removal, up to 20 Francs per tree, but the teams on the ground that did the actual removal were paid more, so while there was also some financial incentive for the farmers, there was even more for the felling teams to pressure them to remove everything.

The felling crews were recruited from the Baumwarte (arborists, or translated literally, tree wardens), a profession that still exists today in the German-speaking world, but generally caring for trees, it must be said. Usually, they came from a farming background, and once they had completed their training, it was a very welcome side income in the winter months. One condition of being allowed to continue in this profession during this period, indeed, sometimes even for acceptance into the school, was that they would also fully enact the policies of the central office on their own farms. Again, these young men were set against their fathers, and they, not wishing to damage the careers of their sons, would capitulate and allow the wholesale destruction of mature trees and a reorganisation of their own farms. This requirement for unquestioning loyalty must really have been some kind of brainwashing, ensuring complete belief in the actions being taken by those crews.

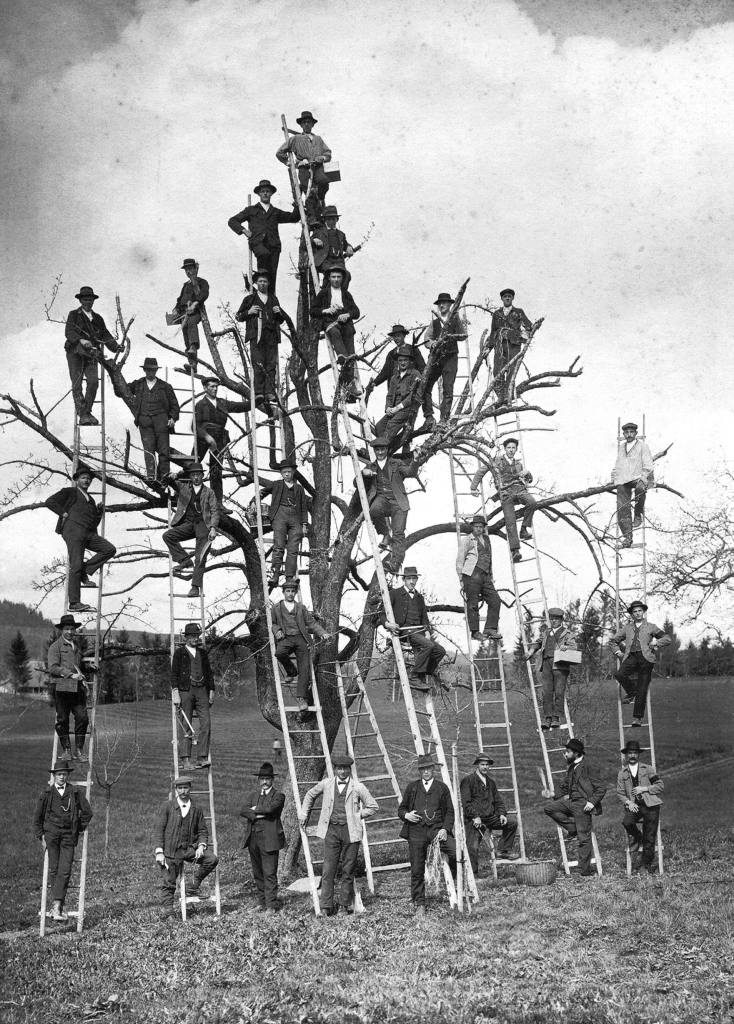

From 1950 the felling crews travelled the country removing trees that had been planned to be removed. They were equipped with modern tractors, winches, and the relatively new one-man chainsaws. Trees were often simply pulled out of the ground using the tractors, but they did have to come up with new attachments to anchor the tractors, such was the strength of particularly the bigger pear trees. In some cases, pear trees proved so resilient to efforts to tear them down they literally blew them out of the ground with explosives. Felled trees were immediately sawn into pieces and, more often than not, massive pyres were built right on site, fuelled with petrol, old oil and tyres, left to burn all winter. The devastation of the once “fruit paradise” that people travelled for miles to see during blossom time must have appeared like hell on earth.

In the first year of felling, during the winter of 1950-1951, around 400,000 trees were felled throughout the country, about half of which were old perry pear trees.

It is interesting to read of the farmers who resisted the push from the central agency. There were always outliers who simply refused to take part, and they were often vilified not just by the government agents, but also by their peers at public meetings, accused of holding back progress. But so too were those who chose to have trees removed but went on a different path for replacements.

I found several 1950s films in the Swiss archives that really give a live impression of what this was all like, and the psychology of how the Alcohol Agency promoted the changes to both farmers and the general public. The standard trees are presented as being in the way and worthless, and the progressive farmer needs to do away with them and rationalise their land for modern techniques. I suspect I view it with a certain cynicism, but you can judge for yourself, as they are also available on YouTube. This short propaganda film, for example, titled “Fruit trees like we should no longer have”.

The captions in this film read as follow:

- Fruit trees like we should no longer have.

- There is only one way to treat such trees.

- There are thousands of trees in our country that do more harm than good to their owners.

- Such trees are no longer cared for, therefore they are pests and endanger the surrounding trees.

- There is only one way – away with these inferior trees.

- If you have a tree, look after it, because it will bring you money.

The replacements

While in countries like Germany, Italy and the Netherlands, the move to rationalise and increase fruit production since the 1920s was characterised by methods we’d be quite familiar with today, using dwarfing rootstocks to create dense, easy-to-harvest plantations of fruit, the Swiss authorities saw this as nonsense. They promoted the planting of half standard trees in well-ordered plots within existing farms, but of course, favouring dessert fruit of a few specific varieties, and trained according to the Oeschbergschnitt method. In a way, it’s almost praiseworthy, as they wanted the growing of fruit to remain part of mixed farming activities, thereby avoiding the creation of a separate class of fruit growers that only grew fruit in intensive farming. But there were people who chose to use this method, usually advised by third party companies. And although criticised for it at the time, it eventually became clear to other farmers that this was a more efficient way of producing quality fruit with less labour.

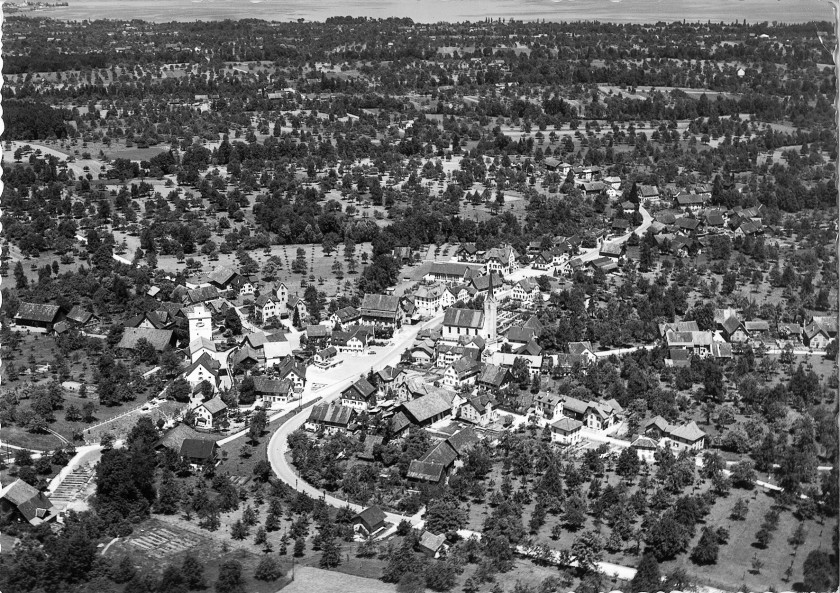

In the meantime, the Swiss landscape was slowly transforming to one of large, open fields with more compact plantations of dessert apples of a select few varieties. The huge variety of perry pears that had established themselves over centuries were denigrated as worthless and, slowly and surely, the diversity of fruit varieties was being eroded, along with the overall rich biodiversity of the entire landscape.

In 1965, the harvest of what remained was not great and, for the first time, cideries had to import fruit as there was simply not enough cider or perry fruit to be had.

The slow resistance

It took an amazing 20 years of the felling action before there was finally a shift in public perception. 1970 was the Year of Nature Conservation, and in that year the tide of opinion slowly began to turn. The newspapers started filling with letters of criticism, expressing an increasing awareness of the environmental impact such wholesale changes to the landscape were having.

The discussion about the decades of tree felling had also shifted at the political level. This may have been helped by the fact that from 1971 the federal government became responsible for all environmental protection; previously this applied only to the protection of water bodies. Conservationists spoke out and warned that the loss of so many trees also threatened the habitat of songbirds, while other writers noted that the loss of so many trees in the landscape also meant the newly opened fields were more prone to erosion and there was no protection from wind or sun.

Despite all that, even in the year of nature conservation, the agency pushed on through and said that the action must go on. In that year of “conservation”, they set a target of 2,000,000 apple trees and 500,000 pear trees to be removed from the landscape before the project would end, a total of 500,000 per year for the next five years. Despite the protests, despite the obvious devastation to the landscape, and even despite the political damage in the later years, the plan continued unabated, with the fully stated intention to rid the landscape of the trees that were being called money-eating, superfluous nuisances by the Alcohol Agency.

By 1975, the plan was complete. It is estimated that by the end of the operations, 11 million trees were destroyed across the entire country, with Thurgau being the most heavily ravaged, its landscape changed forever. Instead of the tree-covered “fruit paradise” that drew people to the region during blossom time, it was now a landscape of wide open, almost treeless fields suited for mechanised farming. And so has it remained.

The present

In 1951, there was an estimated 16.5 million Hochstamm (full standard) apple and pear trees in Switzerland. By 1981, six years after the “reorganisation” had finished, the overall full standard tree stock was 5.5 million trees. In effect, 11 million trees had been removed from the landscape. In Thurgau, once the beating heart of cider and perry production in Switzerland, the numbers fell from 1,486,000 trees in 1951 to 537,000 trees in 1981. Today there are only an estimated 210,000 full standard trees remaining.

Though cider making still appears to be a lively industry in Switzerland, it is nothing near the integral part of agricultural life that it once was. There are still large cideries making modern, mass-produced products alongside juice, and it seems a small number of artisanal cider makers have reappeared in recent years. But perry… that is all but extinct. It is incredible to think that only 150 years ago Swiss perry was was famed across Europe.

There are precious few cideries that have begun experimenting with perry. Ruedi Kobelt, the current towner of Mosterei Kobelt in Marbach, St. Gallen, has made some small batches of perry, and has even experimented with boiling the juice, as the Turgovians did for centuries. But as there are only a few Berglerbirne trees to be found in the region, they had to settle for using whatever perry pears were available locally. By boiling the juice so that the 1.052 gravity increased to 1.072, they ended up with a 9% perry that was then aged in red wine barrels, and they have also experimented with bottle conditioning.

Ruedi Kobelt told me that as the consumption of fermented fruit juices declined, a large part shifted to Süßmost, as apple juice is called in Switzerland. In his lifetime (born in 1958), only apple juice or cider was advertised throughout Switzerland, never perry or pear juice, but apple juice tended to contain about 10% pear juice. And as expected, over the 20th Century, access to beer also had an effect. Kobelt told me:

“During the Second World War, the same amount of fruit wine [would encompass cider and perry] as beer and wine was drunk in Switzerland, about 30 l/capita each. With the opening of the borders after 1945, cheap brewer’s grain came back into Switzerland, the rest you can imagine. Today we have a per capita consumption of about 1.6 litres of cider and about 8 litres of apple juice per year”.

As pear juice became a surplus commodity it was then processed into concentrate and exported with subsidies. In fact, I understand that Babycham was made from Swiss pear concentrate, most likely Gelbmöstler, Schweizer Wasserbirne and possibly Theilersbirne. But a large part of the pear crop was also processed into industrial alcohol or ethanol fuel. However, the end of subsidies by 2000 heralded a further decline of pear trees. The existing obligation of the Federal Alcohol Board to purchase pomme fruit brandy was then overturned and two or three years ago the large cideries basically made it known that they simply didn’t need pears anymore.

Jaques Perritaz of Ciderie du Vulcain is the only other Swiss perry maker I have heard of, making small batch ciders and perries in Treyvaux, but now splitting his time between there and his new cidery in France.

The future

It is truly remarkable how something that had been a way of life for hundreds of years has been so thoroughly obliterated, that even fruit growers and cider makers seem unaware of it. When recently corresponding with a producer of non-fermented pear products near Zurich, he told me that perry was never a thing in Switzerland, but that wine was the most common drink. But we know, without a doubt, that till at least the mid-19th Century, and for a few hundred years before that, East and Central Switzerland was a region dominated by pear trees and perry.

Even the memory of perry as a mainstay of Eastern Swiss culture seems to have disappeared, and schnapps is what people today associate with perry pear trees. That schnapps gradually took over is undisputed, and it is schnapps and alcoholism that is always given as a reason for the destruction of the pear trees in the past. However, as we have seen, the reasons were far more complex, but it is always easy to hang it on a single simple reason that gives some sort of comforting justification, perhaps assuaging the uncomfortable feelings of growers who most certainly knew about the “Baummord”.

I would love to wrap this up with news of new plantings, and a rediscovery of a lost cultural heritage. Indeed, on Twitter I have seen reports of one young Swiss farmer embracing agroforestry, but it seems to be in a vacuum, with no awareness of the history of the landscape there, nor any intention to plant trees for making cider or perry. But I live in hope that someone will capture that spark and put Switzerland back on the perry map again.

Acknowledgements

A very big thank you to Franco Ruault, without whom, many of us would never have heard of the actions that changed the Swiss landscape in so many ways. And special thanks to Franco and the MoMö Cider and Distilling Museum at Mosteri Möhl for the images what accompany this article, and to Ruedi Kobelt at Mosterei Kobelt for his very friendly and open correspondence.

Bibliography

Ruault, Franco, 2021. Baummord: Die staatlich organisierten Schweizer Obstbaum-Fällaktionen 1950-1975. Historischer Verein des Kantons Thurgau. Frauenfeld.

Discover more from Cider Review

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Barry, that was an absolutely fascinating piece. It’s horrifying to think of the cultural and ecological damage that was done in the name of “progress”, and the idea that it was largely driven by the ideological motivations of a few individuals who knew which levers to pull to generate compliance in their schemes… it’s quite chilling.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: The Swiss Tree Murder – Part 1 | Cider Review

Pingback: The Worst Thing we can do is Nothing | Cider Review

Pingback: Orchards, cider and the politics that wreck them | Cider Review

Pingback: Discovering Viez: The Mosel-Franconian Cider Culture of Western Germany | Cider Review

Pingback: Pyrus Invictus – Barry’s CraftCon 2025 Keynote | Cider Review