My partner and I seem to specialise in hiking trips at times of year when no one else wants to go hiking. More specifically, we like to undertake these in wine regions at times when no one else is going for wine tastings. We have spent a glorious winter week in the Alsace and the Mosel valley respectively, walking from village to village and arranging visits to half-shuttered tasting rooms (with varying levels of success) along the way.

There is something fascinating about these off-season vineyards. As you trudge through kilometres of them, you increasingly ‘get your eye in’, and the initially uniform grey-brown of your surroundings fractures into an incredible diversity of green-tinged wintery hues. As you wend your way through the fields, the bare vines are weathered, twisted sentinels watching over the landscape until spring. Mist may well be rolling across the valley floor. Hugging the gravelly path above slopes that fall away with unsettling alacrity, you feel a bit watched, a bit exposed. It’s entirely unlike being in an orchard, which usually has a sheltered, comforting quality even when bare.

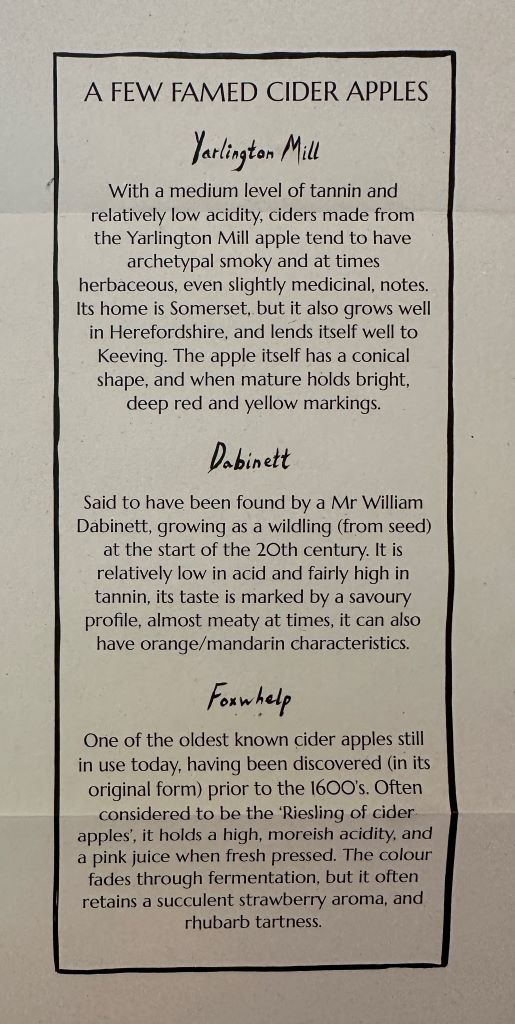

So, we have now spent two successive Januarys in wine regions that are a) within easy training distance of my parents’ house near Frankfurt and b) focused on one grape — Riesling. Yes, both the Mosel valley around the Roman city of Trier and the Alsace (or Elsass) region, the disproportionately sunny strip of land just west of the Rhine that has historically found itself torn between France and Germany, are mostly famous for this one grape variety. 25% of the Alsace region is planted with Riesling; it’s over 60% around the Mosel. When you consider that Alsace is about the size of the Three Counties, it’s fascinating to imagine what the equivalent single variety dominance would look like in cider.

Of course, there is incredible diversity among Riesling wines. Entire wine regions can afford to be synonymous with this grape because it has the potential for incredible complexity and, like any other variety, expresses itself differently when exposed to different weather conditions, soil types, makers’ philosophies, and so on, and is presented at vastly varying sweetness levels. It has become apparent to me over these two hiking-cum-wine tasting trips that Riesling can be a million different things, from zingy and fresh to elegant and floral, from racy and petrolic to dulcet and honeyed.

Is Riesling my favourite wine grape? Maybe. My point here is not that being a Riesling lover is something like being a lover of aspirational cider and perry — in that your favourite drink is far too often misunderstood — but that exploring a single variety of a fruit can be incredibly rewarding. Riesling is just a case study.

As someone who started on their real cider and perry journey only a handful of years ago and still has a huge amount of tasting to do, single varieties are fascinating to me, and I am incredibly grateful to several producers for doing so much to showcase them. Of course, there is a lot of skill involved in blending, and the pursuit of balance is admirable, but I enjoy exploring what a single variety can do, even if it’s predominantly acidic or predominantly tannic or really quite weird. I will drink your SV Flakey Bark and acerbic single-tree wildling cider all day long.

All of this is to say that I was quite excited to receive my first case of Welsh Mountain Cider. Chava and Bill have around 450 varieties planted in their Prospect Orchard in the Cambrian Mountains of Mid-Wales, so it’s amazing that they’re even making single varieties. Few other UK cider makers grow and produce at this altitude. Yes, I’m thinking another hiking-cum-(apple)wine tasting trip is in order.

I’ve got two classic cider varieties in the line-up this time: the bittersharp Kingston Black and the bittersweet Yarlington Mill. I know that Welsh Mountain Cider focus on being as low-intervention as possible in their cider making (something one can probably say for few Mosel or Alsatian Riesling producers, incidentally); as Adam put it in this lovely interview article, their “dedication to the principles of the natural movement is absolute”. Perhaps I’ll have a chance of getting quite close to the essence of these varieties here?

Kingston Black 2020 – review

How I served: Lightly chilled.

Appearance: Somewhat hazy but deep gold.

On the nose: Does anyone else always get a mint choc chip note from Kingston Black? It’s here in the form of a distinctly minty freshness laid over apple-y farmyard notes. This medium-intensity nose is somewhat reminiscent of French ciders: fruity, rustic, and tannic. There’s something a little tropical; peach or even overripe banana. This is quite inviting.

In the mouth: It’s dry, but not bone dry; perhaps that’s because it’s quite fruity. Lightly petillant, it has a medium body. What’s striking is how the nose’s minty note is coming across as reasonably smoky and medicinal, such that it seems almost like an Islay-barrel matured cider at first. There’s light apple skin tannin running through the background, lending pleasant mouth-pucker, as well as medium acidity. The finish is long and dusky, with farmhouse and smoky notes that are reminiscent of an aged cheese (yum). Juicy tannins linger.

In a nutshell: I’m not getting the advertised tasting notes, especially on the nose (“cinnamon, vanilla and buttered toast”), but that’s fine. The cider becomes both fruitier and more Islay-like with time, with strawberry and rubber notes (what is this, Riesling?) emerging on the nose. This feels refreshingly unpredictable and complex as well as moreish, and it has an unusually full-bodied finish.

Yarlington Mill 2021 – review

How I served: Lightly chilled (even more than the Kingston Black, this needs some time out of the fridge to warm up and express itself).

Appearance: Slightly turbid dark orange. What a colour!

On the nose: A relatively delicate nose of nevertheless juicy blood orange and a bit of smoke. It smells like its colour, if that makes any sense. I’m intrigued.

In the mouth: Okay, wow. This is almost like drinking perfume. Very phenolic, bitter, and medicinal. I grasp at straws for a minute or two before realising what it reminds me of: it’s those dark greenish-blue nocellara olives! Then, it becomes very clove-y indeed, accompanied by something floral, perhaps like jasmine green tea, and woody notes. It’s much drier and more tannic than the Kingston Black and has quite low acidity. The tannins don’t pucker; they’re bitter and, well, ‘green’. Paradoxically, the mouthfeel is very soft and smooth, with a long finish of unripe olives and orange pith.

In a nutshell: This is austere stuff, but I love the unusual flavours. I’m not perceiving any of the advertised “light carbonation”. Like the Kingston, it evolves in the glass, becoming incredibly honeyed and waxy on the nose and palate with time. Specifically, it reminds me of a fancy local honey procured at a farmers’ market in near-crystallised, creamy form and somehow rendered sugar-less — lovely. Unfortunately, the cider then went a bit subdued as it sat, but I guess one shouldn’t leave good cider sitting around. It’s alive!

The horse is well and truly deceased by now, but I must say these ciders would pair very well with some good food. Pairing the Yarlington would require care to ensure balance; perhaps some salty, fatty smoked mackerel alongside the traditional sharp, green gooseberries? I ended up nibbling some hard Swedish Västerbotten alongside these ciders. If you haven’t tried this cheese, it’s an amazing combination of grassy young creaminess and umami-rich amino acid crystal goodness. It was an excellent pairing, to be sure.

Did I glean the single variety insights I was hoping for on this brief excursion sous bois in the Cambrian Mountains? Well, I certainly perceived the spiced clove notes Yarlington Mill is known for, and the Kingston Black clearly exhibited the holy trinity balance of sugar, tannin and acidity ascribed to that variety. However, both ciders also surprised me a great deal (for example, the Kingston was certainly ‘smokier’ than the Yarlington).

Over the coming years, I’m sure I’ll get a better handle on the recurrent characteristics of Kingston Black or Yarlington Mill. For now, I’m content to marvel at how complex a single variety can be.

I appreciate your adventurous tasting spirit. And ability to put tasting experiences into words. Very fun read – not least because we visited Prospect Orchard recently and it was nice to revisit mentally while reading this piece.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Much appreciated, Patrick! I would love to visit too.

LikeLike