My first-ever article for Cider Review, just over a year ago now, was my call to celebrate a still underrated pome, the glorious quince. Having attended a CiderCon panel talk on quince organised by the ineffable Prince of Quince, Brandon Buza, a few months ago, I thought it was high time to revisit this topic.

During the panel, we tasted six quince drinks—the longest tasting line-up of any CiderCon talk I attended—all of which had their own personality. In fact, the first and last were quince juice: we started with heady cocktail of rose, citrus and sugar that was Empyrical’s northwest–Washington cryo-concentrated “quince nectar” and ended with a partially fermented, much more savory number which I believe came from Two Broads in southern central California. Throughout the rest of the line-up, citrus, evergreen, prunes, apple, fino sherry, rose, caramel, and even dill all made an appearance in my tasting notes, while the cubes of fresh Kubanskaya quince that were passed around for comparison had an addictive bite and refreshing mild zinginess (don’t let anyone tell you quince can’t be eaten raw!).

Adam Wargacki from Empyrical laid out the cider-maker’s options with quince as follows: a field blend “with quince on the margins” (c. 5%), quince cider (c. 50%), and 100% quince wine, a still largely unexplored category. But as panel member Matt Sandford said, “a lot can be a little and a little bit can be a lot”: the 100% quince drinks we tried were full of mystery and complexity, while those that contained only up to half quince juice were sometimes much more overtly quincy.

Attendees also learned about handling the quince’s at-times fickle ripening behavior: “I’m not sure anything is more important than the ripeness when it comes to quince—even varietal,” Brandon claimed. He also advised that “sweating is not really a thing — don’t keep your quince for more than a week!,” while Matt quipped that “if you’re having rot, you should press faster.” When the very high pectin level of especially under-ripe quinces was raised as a potential issue, Matt intoned, “Patience is better than pectinase.”

The quince terroir of CiderCon’s guest country, Chile, was also showcased. The Chilean delegation related how in their home country, every old orchard has one quince tree planted in it for making membrillo—a classic—and that beyond that, quince is mostly grown by canals in dry country, where it benefits from lots of sunshine. One of the delegates, José Antonio Alcalde, associate professor of fruit growing and enology at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, explained how makers can work with maceration to increase floral or fruity flavors and lower tannins and terpenes, while another, Rene Galindo Quidel from Sidrería Tencai, noted that, given he doesn’t know the varieties of the quince he’s using, he uses harvest time, lagering, maceration and other techniques to play with flavor. Matt, who used to work at Alai Cider in central Chile is now head wine- and cider-maker at Rose Hill Farm in New York’s Hudson River Valley, said he only grows Quince A these days (yes, the rootstock): he doesn’t generally like the quince where he lives, as the flavors are too green and vegetal for him, and he thinks you really need a hot, dry climate for full ripeness.

With all these quincy thoughts still bubbling in the brain and the Quince Fest tea-towel that was slipped my way at CiderCon hanging by my sink, I sat down (metaphorically speaking) with Brandon to talk a bit more about our shared fixation.

Cider Review: So, why do they call you the “prince of quince”?

Brandon Buza: That’s a fair question. Honestly, I don’t remember the origin anymore! What I need to make clear is that I didn’t come up with the title.

It is fun to say, however, so I would bet money Erik from Press then Press was involved. That said, quince has other royalty, so it’s not as weird as one might think. There is a Queen of Quince, a King of Quince and a Quince Queen, although none of them ferment quince.

CR: What was the inspiration for the panel at CiderCon?

BB: The panel was the result of my continued interest in the fruit, and it came right after a wildly successful first Quince Fest in Portland. Also, I’d pitched a quince panel in the past, but it wasn’t green–lit until this year when the ACA approached me. I should also mention that some of the things that we did for the panel (fruit tasting as one example) were all things I’d tried before with great success.

CR: Are there a few key points you’re hoping attendees took away from it?

BB: I just want people to have a better understanding of a deeply misunderstood fruit. There are countless articles published in both print and online that simply get it wrong: that it’s inedible unless cooked, that it’s too hard to extract any juice… I jumped in and started asking my own questions and doing my own research, because it was crystal–clear than nobody else seemed to be. The quince has so many redeeming qualities.

CR: I’m tasting three quince ciders from three continents for this article. Can you generalise about the flavours of fermented quince from different geographical locations, e.g. UK vs US?

BB: I wish I could generalise, but I don’t think I’m in a position to do that yet with any conviction. My thoughts are constantly evolving as my experience with the fruit grows. As soon as I tell you one thing, I’ll be proven wrong a season later. Quince doesn’t reveal herself that quickly, and I’m okay with that.

CR: You must have sampled hundreds of quince ciders in your time. Do any favorites stand out?

BB: I have had a LOT of quince ciders (from 5% quince to 100%) over the past five years or so. Generally, the winning bottles are those where the quince shines through from start to finish. I want the full quince experience, with those otherworldly quince aromatics coming through.

Early in my journey, bottles by Ramborn, Art + Science and Tilted Shed each made favorable impressions and helped me sketch out what I wanted from my SV quince wines/ciders.

CR: What’s next for you and Cydonia?

BB: Well, I certainly hope we can complete some research on the juice in the coming year. Every year brings us a little closer as more and more people express interest in the fruit and a desire to test the juice in a lab. I’ll spend some time in the coming months reaching out to researchers and the like.

In the interim I’ll just be working with the quince community to learn as much as I can. There are some really passionate players out there, and I really enjoy those conversations. Also, knock-on-wood, for now the trees in my orchard look fantastic, so I’m hoping for another good year.

I will mention that I do have one really exciting quince project that I’m trying to get off the ground: a quince beer. I’ve done very little brewing, so that’s not an area of expertise for me, but it’s something I would like to play with as another avenue for using our friend the quince. The fact that it has been used infrequently in beer is interesting to me.

CR: Quince beer sounds awesome! Hopefully I’ll get to try it at the next CiderCon.

While the quince panel was one of my favourite things at the conference, this article is also about giving me an excuse to make a dent in my stash of quince drinks. Sadly, I don’t have my own quince orchard (yet), but I do have a small but growing collection of quince ciders and wine that are apt to start narrowing my corridor if I don’t get to it.

Let me take you on a small international quince voyage across three continents. Still and sparkling, sweet, sour, and even salty, two are 100% quince wines (“quincies”, if you must) that come from Mediterranean climates (inland Oregon and central Chile), and the other is a quince-enhanced cider from the milder climes of western Cornwall. Given my last quince article tasted three English drinks, which (while diverse) all shared the delicate rosiness of classically blossomy quince in common, I am really interested to see what this international set has to offer.

First up is Art + Science in Oregon’s Willamette Valley. Although I procured this bottle from Press then Press (it has sold out since, but it’s still available from other US outlets), I had visited Kim and Dan of Art + Science this past summer while on a road trip through the Pacific Northwest. The two of them gave me (along with my unwitting grandmother and sisters) the most wonderful tour and tasting. The quince drinks stuck with me: made of foraged fruit from the old farmsteads of the Willamette Valley, which feels like a surprisingly off-the-beaten-path place given it’s a major wine region, they’re bold, punchy and savoury—wild-feeling. Let’s see if this bottle follows that theme.

Art + Science, Quince 2020 (USA) – review

How I served: Chilled but not frigid.

Appearance: Cloudy but shining orange-gold with lots of bubbles (my glass almost has a head!).

On the nose: A surprisingly sugared, sherbety strawberry smell hits me first. It’s a bright and intense nose, with more orange-coded apple and mango notes as well. A vanilla-cum-rosewater undertone (maybe that’s the barrel aging?) emerges with repeated sniffs. This is complex but recognisable quince.

In the mouth: Pow! That’s some acid. Whatever that nose was has been stripped of its sugariness and been pickled. There’s an acetic twang and a good amount of bitterness, both enhancing a salty moreishness that reminds me of olives. A good effervescence, too. This would be brilliant with some porky food.

In a nutshell: Bold and tart, this quince isn’t demure—I love the contrast between the nose and palate.

Well, that was classic Art + Science. I have far less experience with the next maker; they’re over 7,000 miles away from me as the crow flies, just south of Santiago de Chile. However, I did get a fleeting taste of the 100% quince cider reviewed below at CiderCon, and I was excited to crack into my own bottle once back home.

Alai Cider, The Pome King (Chile) – review

How I served: A little while out of the fridge.

Appearance: Cloudy, dull, orangey gold.

On the nose: A rosy but savory quince nose with hints of green-ish banana. That’s a new one on me!

In the mouth: Big but slightly green tropical fruit, like a mango with its peel. Quite sour, but not bitingly acidic. There’s a saline, nocellara olive flavour, which clashes delightfully with more off-dry banana vibes. The accompanying thick texture jibes with what I read about maceration being part of the process of making this drink. I’m surprised, though not disappointed, to find it’s practically still. I know that this is from a warmer region of Chile than the more southern–Chilean quince drinks from that country which I tasted during the panel, which checks out given the intensity.

In a nutshell: An intriguingly rich, tropical-skewing quince, if a bit green around the edges.

Now, another product of maceration—this time quince macerated with the pomace of classic Cornish apple varieties before pressing. James of Vagrant Cider doesn’t live far from me in Cornwall; I’m delighted to get to try what quinces local to me have to offer.

Vagrant Cider, Longarm (UK) – review

How I served: Lightly chilled as per the recommendation.

Appearance: Beautifully clear and pale yellow-gold with a nice shine—I find quince is often either super-clear or super cloudy.

On the nose: A little reticent at first, with hints of concentrated apple juice and maybe a bit of that characteristic quince rosiness. The smell acquires more body and earthiness with time and warmth, although it remains light. Some biscuit character.

In the mouth: Immediately noticeable is the very creamy, silky mouthfeel; I wonder if this has also undergone malolactic fermentation. The flavours aren’t as present as the texture: there’s a very German-style apple character (i.e., an acid that’s very present but also slightly muted, complemented by some quite herbal bitterness from the subtle but present tannins), a touch of sweetness, and that earthiness like berry seeds. As the cider warms and becomes less reticent, this is reminding me more and more of just-ripe raspberries, or…sea buckthorn? Sea buckthorn!

In a nutshell: The flavors aren’t intense, but sea buckthorn is a note and a half, reflecting the subtle complexity awaiting this cider’s patient drinker.

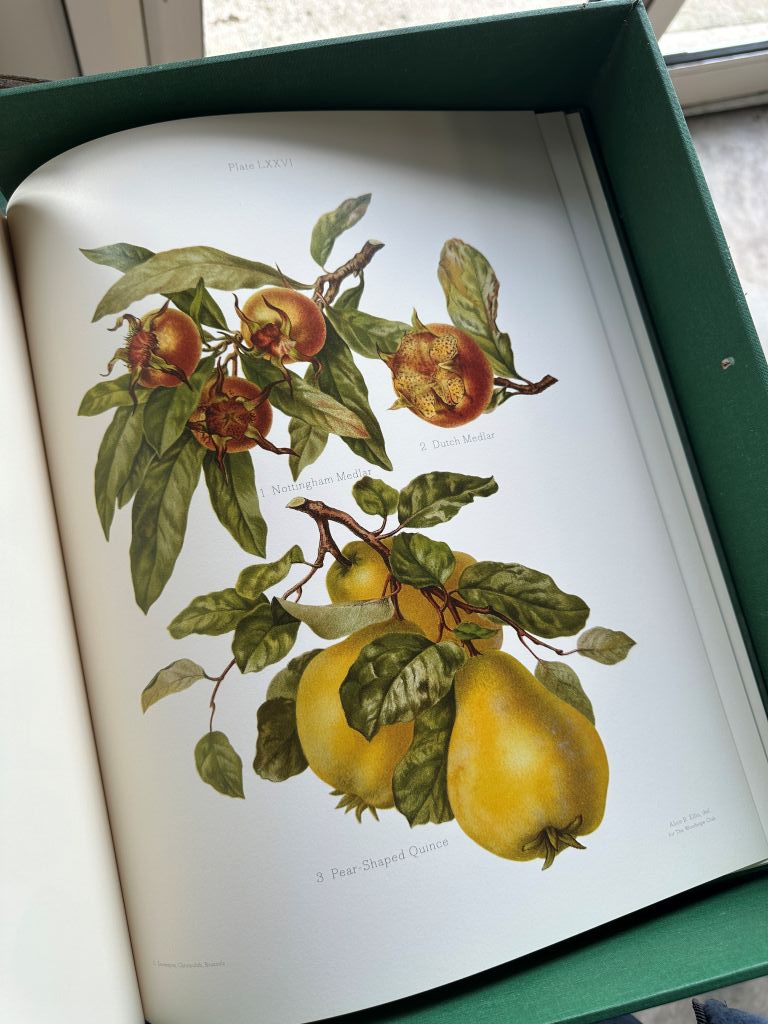

I now feel silly for asking Brandon to generalise about the flavors of quince around the world. With the flavors of membrillo or quince jelly always to mind, one can overlook the staggering variety and complexity of fermented quince, even as we’d hardly generalise about the taste of “apple cider”. As Adam from Empyrical pointed out during the panel, there are just 15 illustrations of quince varieties in the USDA’s collection of pomological watercolors, whereas thousands of apples are depicted.

The upside? With quince, one is always a rather intrepid explorer. Bon voyage!

Discover more from Cider Review

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.